Operations, risk, and small firms: Field results from irrigation equipment vendors in Senegal

Handling Editor: Edward George Anderson

Accepted by Edward George Anderson

Abstract

What are supply chain management challenges in a lower-income economy, and how do managers at smaller firms address them? This field study presents these challenges from the perspective of the 60 managers who run firms selling irrigation equipment in Senegal. By canvasing 35 cities, we gain unique visibility into how private supply chains, on which public officials and smallholder farmers in Africa rely, effectively deliver agricultural goods. The primary challenges for managers in this supply chain are day-to-day risks that are quality and contractual in nature and have financial implications. City size in combination with supplier type, firm size, and manager network determine risk exposure. Firms’ efforts to manage the chain are more reactive than proactive and more informal than formal, which reveals an opportunity for public agencies to support supplier and customer coordination. Public decision makers should tailor support to account for the differential risks that city size brings to supply chain management. This support should include not just financing the firms directly but should also entail giving loans to customers, certifying suppliers, and sharing inventory risk with public and nonprofit partners.

1 INTRODUCTION

The development of agriculture and the rural economy must be accompanied by promoting small and medium enterprises…. In this context, effective integration into foreign markets guarantees the chance to redeploy national economic activity through a better structured agri-food chain.

(Plan Sénégal Emergent, Commerce Section, p. 54 [translated])

Senegal's national economic plan supports small firms, streamlining the distribution of agricultural equipment and the production of vegetables, cotton, peanuts, and rice. Since cabinet and interministerial meetings in July 2020, Senegalese President Macky Sall and ministry leadership have been reviewing the support that nearly 20 public agencies give to small firms.1 In Senegal and across Africa, policymakers, perhaps driven by development-economics research on microcredit, have zeroed in on solving small firms’ credit constraints. This issue is important, but an overwhelming focus on it misses other supply chain challenges that face these small firms. What are these challenges, what policy support may assist small firms, and how can it be targeted? Cheik Seck, the former Director of Foreign Trade for Senegal, recognized as far back as 2007 that identifying the needs of small firms requiring forms of support in addition to financing is a pressing concern (Seck & Mbaye, 2007).

In this field study, we use firm-level survey data organized by a rigorous qualitative coding process to reveal the supply chain challenges of irrigation sector firms, from large importers to last-mile retailers, and to identify opportunities to support them in practice and further research. We gain visibility into the chain, to a degree that is unique in existing development operations work, by surveying firms in 35 cities in Senegal. Responding to the ongoing policy debate about support to firms in Senegal and other lower-income countries, we answer two questions: What are managers’ supply chain risks and existing management strategies? Do risks and strategies vary with city size, and what factors moderate this relationship? In our discussion, we address: How may Senegal and similar countries identify and support firms facing risk? Do these risks and associated management strategies differ from those in higher-income economies?

There is little empirical supply chain management evidence that describes for decision-makers smaller firms’ risks and management strategies in lower-income countries. The scant research, even at the qualitative level, stems from the fact that data, especially from multiple firms and cities, are extremely difficult to gather. Rather, existing research uses convenience samples to generate insights primarily in Chinese and Indian markets; these samples skew upstream and represent challenges for very different economies from those of Senegal and the other 45 least developed countries (LDCs; UNCDP, 2021).

Across the LDCs, 36 of 46 of which are in Africa, private firms in liberalized economies like Senegal deliver products central to the livelihoods and health of more than one billion people. Given the potential of irrigation across Africa, we focus on the irrigation supply chain, which delivers two types of equipment necessary for agricultural policies to positively impact farmers. Investigating the supply chain challenges of firms in the irrigation equipment sector is especially timely because of the role irrigation plays in climate change, gender equity, and nutrition policy. Lessons about this supply chain may also offer general insight into similarly distributed, sized, and valued goods, such as medical products like crutches, agricultural machines like pesticide sprayers, household appliances like clean cookstoves, and microinfrastructure like solar panels.

We introduce an operations perspective to the active policy debate on what support to deliver to firms and how to target it. In the LDCs, public agencies generally deliver loans and sometimes information to firms identified based on their size and to some extent their suppliers. For example, medium-sized rice mills in Senegal benefit from low-interest credit. We provide some of the first empirical evidence that indicates the need to support firms other than with loans. We also indicate the potential of targeting this support using factors other than firm size, helping grow the policy toolbox used to aid firms essential to policy delivery. In the broadest terms, with this study, we aim to give decision-makers evidence needed for policy action to mitigate risks to these firms. This action can be taken in addition to the action already being taken to alleviate their (primarily credit) constraints.

Our empirical contribution is fourfold. First, the irrigation supply chain does not extend into many cities in remote rural areas, depriving local farmers of ready access to equipment and indicating that a major policy opportunity may be to extend it. Second, its managers face a mix of contractual and quality risks with financial implications; the most common risks are customers not repaying sales on credit (32 activities) and products being broken on arrival (20) and after sales (18). Third, risks are not homogeneously spread across activities but are moderated by city size, alongside supplier type, firm size, and manager ethnicity. These factors have been recognized by agricultural policy and political science research as being instructive for understanding commercial and public decision-making in countries like Senegal. Fourth, firms’ efforts to manage risk are more reactive than proactive (40%) and informal than formal (13%t); this finding, taken together with our other insights, suggests an opportunity for public decision-makers to support supplier and customer coordination to mitigate risks.

In Section 2, we summarize the supply chain literature as well as the policy and political science research relevant to irrigation and small firms in Senegal. We present in Section 3 the field study, including its site, sample, validity, and limitations. We report our results in Section 4 and discuss implications for future research and policymakers in Senegal in Section 5. Section 6 concludes.

2 LITERATURE

2.1 Sector view

Agricultural supply chains in Africa are necessary for development policies to be effective. Before international financial institutions imposed reforms on African countries in the 1980s that moved economic activity out of the public and into the private sector, public agencies handled both irrigation policy and supply (Gore, 2000; Ndiaye, 2013). Today, public decision-makers set policy while private firms “deliver policy,” or sell equipment, enabling public programs to benefit the 51 million African farmers (Lowder et al., 2016). Our analysis centers on the private firms that link farmers to irrigation equipment.

Irrigation equipment reduces uncertainty for farmers and is grossly underutilized. In Africa, 29 of 30 irrigable hectares are unirrigated (Xie et al., 2014). Irrigation could improve food security for 185 million people (Burney et al., 2013); enable effective farmer credit or contract farming initiatives (e.g., Rosch & Ortega, 2019); permit farming (high-value) vegetables, including in Senegal (Van den Broeck et al., 2018); and let countries, such as Senegal, work toward food self-sufficiency with another growing season (Van Oort et al., 2015). There is perhaps a paradox in that irrigation equipment reduces farmers’ production risks, whereas firms distributing it shoulder a range of business risks. Our study examines the firms that overcome such risks to make irrigated farming possible.

The supply chain for irrigation equipment is a major impediment to realizing farmers’ welfare gains (Burney et al., 2013). In response, African policymakers at a high level coordinate commercial activities to facilitate irrigation and mechanization for smallholder farmers (NEPAD, 2014). In Senegal, donor strategies recognize the “countless firms” that enable agriculture sector growth (USAID, 2018, p. 8). Our work addresses the challenges in this chain that African governments and donors recognize as crucial to policy.

Diagnosing specific challenges in irrigation equipment supply is difficult because of scant data across cities and firms. Colenbrander and van Koppen's (2013) survey of 21 pump retailers in Zambia is the main such effort at this time. They document importers in the national capital procuring from offshore manufacturers, mostly in Asia, and selling to a few rural retailers (see also, De Fraiture & Giordano, 2014). They find that retailers offer low-quality pumps and limited after-sales services. The supply chain issues they document motivate a study to systematically explore firms’ challenges and management practices, especially in areas beyond a country's capital and largest cities.

Donors and agencies work to “support” small firms. A quite common form of support is loans, given the wide-ranging credit constraints in lower-income countries (for a review, see, Dalberg, 2011). There are, however, other promising varieties of support, such as information sharing, insurance, and regulation, that may better meet needs. A common way of targeting support is to use firm size (for a review, see Kersten et al., 2017). There are, however, other promising factors beyond size and, to some extent, supplier type that may better steer support. Supplier type, while used to organize chains coming from farms (e.g., farmer, buyer, miller, supermarket), is not usually applied in a nuanced way to organize firms in chains leading to farms (e.g., importer, retailer, farmer). In one sector in Senegal, small firms have a 15% probability of being aware of public support and a 4% probability of using it, which may be due to programs not meeting needs and firms in need not being targeted (Cirera et al., 2021). New varieties of support and targeting require an understanding of the supply chain. The core policy concern this work addresses is that there is neither systematic evidence on how firms may be targeted for supply-chain interventions in ways other than size nor on what support firms may benefit from in addition to loans.

2.2 Academic view

Recent operations management research examines challenges related to supply chain management for irrigated farming. Agricultural policy research increasingly highlights the supply-side barriers to irrigation policy, and along with political science work explores how city, firm, and manager characteristics moderate economic activity in lower-income economies.

2.2.1 Supply chain management

Supply chain risk management is paramount to effective chains but undocumented in lower-income economies. Companies in higher-income economies coordinate their chain with formal contracts to manage risks. However, between developed and less developed economies and crucially between urban and rural areas of less developed economies, there exist differences in the reach of infrastructure, access to finance, and cost of enforcement in legal systems. In light of this variation, supply chain management insights may not apply to the majority of firms in the world (see, e.g., Lee & Tang, 2017; Sagasti, 1974). Yet, few field studies identify how these operations work and explain how they may differ.

There is research in operations management on irrigation infrastructure and farmer decisions, but not the firms that make irrigation possible. Research through the 1980s focused on making infrastructure decisions to extend irrigation to farmers (Rose, 1973). Recent work focuses on the problems that farmers face. Dawande et al. (2013) propose an optimal distribution of irrigation water to farmers at different distances from canals. Huh and Lall (2013) model a farmer deciding to allocate crops, irrigate the land, and accept a contract. These studies are a part of a growing line of analysis on farmer decisions (e.g., An et al., 2015). Yet, research has not analyzed the firms that make irrigation possible.

Analytical work indicates that understanding smaller firms is necessary to improve decision-making in lower-income economies, especially in solving last-mile operations challenges. Iyer and Palsule-Desai (2019) use a principal agent model to show how a manufacturer should assist multiple retailers (how to work with small firms is the focus of related work on multinationals’ reputational risks and sourcing and selling practices). Gui et al. (2019) show theoretically that a nonprofit wholesaler can create supply chain inefficiencies in a regulated market. Focusing specifically on last-mile firms, Sodhi and Tang (2014) use a stylized model to show how coordination can improve flood response outcomes. However, we are unaware of empirical supply chain work on small firms, especially in Africa.

Empirical operations work on lower-income economies addresses manufacturing and/or firms in Asia. Empirical studies document manufacturers’ problems (e.g., Amoako-Gyampah & Boye, 2001; Castañeda et al., 2019) and those of firms in the Indian and Chinese markets (e.g., Dong et al., 2016; Shou et al., 2016; Sreedevi & Saranga, 2017; Wang et al., 2016). These studies use convenience samples, often from online surveys or business plan competitions. Inventory and quality risk may be moderated with some types of contracts (Castañeda et al., 2019; Mitra et al., 2015), and contractual risk in the Chinese market may be mitigated by factors including social ties (Shou et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016), two important facts on which our study builds. Yet, a liberalized economy in Africa differs from that of India with its extensive manufacturing base and China with its industrialized socialist-market economy. These differences make how small-firm managers run chains in Africa a major unanswered empirical question.

2.2.2 Policy and political science

Supply chains are essential to irrigation policy but are understudied. In agricultural policy research, the interest in irrigation supply is related to how farmers adopt, and continue to use, equipment. Aryal et al. (2019) show that, in general, being far from a market means that households are less likely to adopt equipment, indicating that local retail is an important determinant of effective policy. Nakawuka et al. (2018) find that farmers face equipment unavailability and no guarantees on after-sales services. Existing research identifies key supply-side challenges but does not investigate how firms operate.

Small firms are key to positive farm-policy outcomes. Existing studies focus on small firms that participate in public programs. Yet recent work and our study build more generalizable evidence by canvasing multiple cities to study firms not necessarily in public programs. One survey in four Ugandan cities traces quality issues in the chain and finds that deliberate adulteration is not common (Barriga & Fiala, 2020). Another 96 Senegalese firms show that firms further from markets respond less sustainably, such as using distress selling, to climate shocks (Crick et al., 2018). This expanding evidence base, some that are attentive to the role of city size in risk exposure, generally does not address how firms manage risk.

City characteristics matter in managing goods and services. City size relates to the legal, financial, and built environment, which varies widely within lower-income countries. Agencies and nonprofits in lower-income economies, as a function of their location, face different challenges in delivering services. Kosec and Wantchekon (2020) summarize: “Service delivery is especially difficult in rural areas [given] unique logistical challenges.” We test the hypothesis that firms face different supply chain challenges in big versus small cities, like their public and nonprofit counterparts.

Firm size influences business practices. There is a long line of research on small firms in developing countries, broadly focused on their economic benefits (Kersten et al., 2017; Tendler & Amorim, 1996). Firm size is typically related to formality, which bears on risk exposure vis-à-vis access to banks, courts, and other institutions. Size also impacts access to technology. In Senegal, for example, one in four smaller firms cites demand uncertainty as a barrier to digitizing business processes (Cirera et al., 2021). We test the hypothesis that bigger firms, perhaps through more access to institutions and technology, have different supply chain risk exposure and management strategies than smaller firms.

A manager's network shapes what economic activity is feasible and successful, especially in a more informal economy. There is work in development and political science research, with parallels in operations management (Cui et al., 2013), on how ethnicity structures public and commercial decisions. In Senegal, ethnicity, even in rural areas, is a less salient feature of public service delivery (Wilfahrt, 2018). Yet, a conjoint experiment suggests that in Senegal, ethnicity and religion may shape, among other barriers to trade, perceived contractual risk (Bhandari, 2022). We test the hypothesis that ethnicity, specifically being in the majority ethnic group or not, affects commercial supply chain risk.

3 FIELD STUDY

This field study is based on unique survey data of firms across multiple tiers of the supply chain and cities. The intent was to collect data from all firms in the Senegalese irrigation supply chain that sell irrigation pumps and/or pipes. In the chain, we study firms that distribute to other firms and/or retail to farmers, farmer associations, the state, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). In canvasing 35 cities, we interviewed 60 firms, of which 20 sell both pumps and pipes and 40 sell one or the other.

3.1 Design

This field study uses a census-type approach to systematically canvas firms in 35 towns and qualitative methods to parse the survey data as outlined by Eisenhardt (1989) and Yin (2003), adopting grounded theory to organize open-ended responses to questions about risk. Meredith (1998) writes, if “cost, time, and access hurdles” can be overcome, a field study like ours is appropriate for investigations where the phenomenon is not yet well understood. Data collection entailed 10 person-months of canvasing cities to connect with managers in French, Wolof, and Pulaar in far rural Senegal.

3.2 Context and external validity

Senegal, in terms of its private markets, is a representative LDC, a set of 46 countries with agrarian economies. Private firms, including irrigation-sector firms, deliver essential agricultural goods and services (Ndiaye, 2013, p. 139). Relatively stable political and market institutions support 4%–5% per year of economic growth. We believe our results are relevant to the other LDCs. LDCs’ economies are quite different from China and India, where related supply chain research primarily occurs. China and India have extensive manufacturing bases and can shape production and distribution in ways typically not observed in LDCs.

Senegal in its irrigation coverage is somewhat positively atypical for Africa, having irrigated three in 10 irrigable hectares. This is not attributable to a unique supply chain per se. We find that its irrigation supply chain structure aligns with piecemeal evidence on irrigation chains elsewhere. Rather, its coverage seems attributable to standard government efforts to increase agricultural production (Tendler & Amorim, 1996), which have primed the demand for irrigation (Ndiaye, 2013). Yet, irrigation remains a policy concern; for instance, coverage of fruit (31%) is low (FAO, 2016, p. 9). Additionally, the extent of coverage, with at least $32 million per year of equipment flowing to farms (FAO, 2016, p. 11), means there are firms to identify and interview. We are confident that these results are germane to discussions in Dakar and to the governments contemplating efforts to boost farming output in the eight arid river basins that cover half of the continent.

Senegal's irrigation systems are representative of those in other lower-income economies. Some 225,000 farmers irrigate their fields (based on restricted-use data; ANSD, 2018). Farmers use pumps attached to pipes to feed river water into 1–2-m wide canals and repair and maintain equipment and canals themselves. The similarities in irrigation systems between Senegal and other African countries make this work practical beyond Senegal.

Finally, insight into Senegal's irrigation chains may serve as a relevant starting point for research and policy work on the broad genre of similarly distributed, sized, and valued goods in African economies, which also have health and welfare implications. These include medical equipment (e.g., wheelchairs, crutches), household appliances (e.g., water filters, clean cookstoves), agricultural machines (e.g., pesticide sprayers, hand-held plows), and microinfrastructure (e.g., solar panels, semipermanent latrines).

3.3 Site selection

Our intent is to identify all cities in which firms selling irrigation equipment could be located. First, to determine where to focus, we use administrative data to identify two areas where public irrigation agencies work and mechanized irrigation occurs. These are the Senegal River Valley and the Anambé River Valley. These areas produce 78% of all rice, often an irrigated crop (ANSD, 2017).

Second, we select 35 cities to canvas. Senegal refers to the places we canvas as cities, and so do we, even if in other contexts some may be called towns. Our guiding principle is to select cities in the irrigated areas in which government administration (and commerce) occurs, which aligns with key informant suggestions and recent studies (Barriga & Fiala, 2020; Crick et al., 2018). Cities where administration occurs are termed communal, department, regional, or national capitals. We report the selected cities by type in Table 1. In the two irrigated areas, we select 33 capitals to canvas. We exclude five capitals more than a day's travel from the irrigated areas that are so unlikely to sell equipment and four extremely small capitals that are too difficult to access. Outside the irrigated areas, we select large and commercial capitals en route to the irrigated areas: we include the national capital (Dakar) and a regional capital that is the economic hub of southern Senegal (Tambacounda). Hence, the final design encompasses 35 cities. Twenty-six of the 35 cities are commune capitals, with a median population of just 8373.

| Count Cities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital type | Senegal River Valley | Anambé River Valley | En-Route to irrigated area | Rowtotal | Median population |

| National | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1,056,000 |

| Regional | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 103,994 |

| Departmental | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 14,802 |

| Communal | 21 | 5 | 0 | 26 | 8373 |

- Note: For example, we select 21 cities that are commune capitals in the Senegal River Valley. Population data come from Senegal's statistic agency (ANSD, 2016). In Senegal, the smallest cities are communal capitals, followed by departmental capitals that govern 3−7 communes, then regional capitals with 3−6 departments under each, and finally the national capital (Dakar).

3.4 Respondent identification

Next, our intent is to identify all firms in these cities that sell irrigation equipment. We identify 75 firms and interview 60. The interview guide is discussed in Section 3.5. The field research team was made up of two researchers, each paired with an enumerator. We conducted pilot visits to three cities.

First, upon arriving in each city, the team identifies commercial neighborhoods of the type identified in the pilot work as hosting firms selling irrigation equipment. These neighborhoods surround a city's major roads and host markets or include the grandée mosque or mayor's office. These areas usually overlap (in Dakar, we canvas the five main commercial-trading neighborhoods).

Second, the team approaches the three types of firms that our pilot visits suggested might sell pumps and pipes. Examples of these firms are shown in Figure 1. These are agricultural firms selling farm inputs and durable equipment; firms selling and repairing machinery (such as motorcycle engines, which are similar to pumps); and hardware firms selling electronics and construction materials and, in four rare instances, primarily pumps. We identify an estimated 1100 candidate firms that might sell pumps and pipes based on their names, signs, advertisements, and products on display outside and inside.

Third, for each candidate firm, we did an initial two-question interview (that nobody declined) to see if they sell pumps or pipes. Of the roughly 1100 firms, we find 75 firms that do sell pumps or pipes. Of the 75, 60 consent to be fully interviewed (the 15 declines are slightly more prevalent in large cities). We speak with a person in a managerial role with knowledge of operations, returning if one is unavailable. Of the 60 firms, six are agricultural input firms, eight are machining firms, and 46 are hardware firms; the predominance of firms not primarily in the agriculture business differs from stylized understandings that suggest such a chain is made up of small agricultural shops specialized in farming.

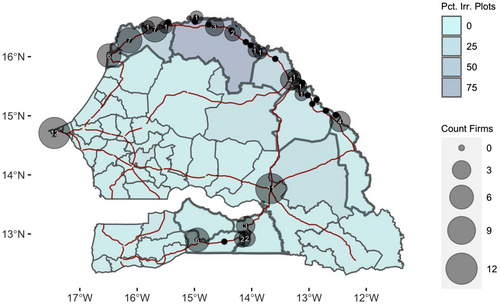

Fourth, at the end of an interview, the team asks if there are other firms in the city that should be interviewed. From the answer, we do not identify additional firms that we were unaware of by visual sampling. This indicates that our approach was likely comprehensive. In Figure 2, we display the cities in which we interviewed firms relative to where irrigated farming occurs.

Map of cities selected and firms interviewed.

Note: The width of a circle is proportional to the count of irrigation-industry firms in a canvased city. A solid black dot represents where each canvased city is. The percent of irrigated plots is represented by the shade of the department, with darker departments having a higher count of irrigated plots. Irrigation data come from the 2018 restricted-use farmer census (ANSD, 2018). Outlined departments represent those where mechanized surface-water irrigation occurs. The national roads are represented by the red lines. Roadway data are from the World Bank's Senegal Roads dataset

This approach is feasible in terms of the time required. More than half of the cities are surveyable in a few hours. Nine of 35 cities required visits over 2 days; five of 35 required 3 days; and two of 35 required 6 days.

3.5 Interview process and guide

The interview guide is available in Supplement Table S1 and includes 53 questions, most of which require one-word answers and were designed for and administered to managers. We focus the interview on the firm's “middle range” pump and/or pipe in terms of price. For each product, we ask about its sourcing, stocking, and selling practices. In addition, we briefly cover the firm's customers (e.g., farmers, other firms), suppliers (i.e., location and type of firm), and partners (e.g., the government), as well as the firm's other products.

The core two-part open-ended question is: What is a risk that comes from being in the [product] business? We clarify with “what uncertainty is associated with sourcing, stocking, and selling [product]?” Next, for each risk, we ask, “how do you address or manage that risk?” We clarify with “what strategies do you use to address that risk?” We define risks for respondents as the uncertainties that can arise from being in the pump and/or pipe business. We define risk-management strategies as how the firm addresses a risk or its impacts. About one-quarter of the time, we prompt that a risk, if well managed, is not necessarily a problem. We encourage the respondents to cite all sizes and types of risks and strategies.

For this question, there is a trade-off between (1) giving managers a list of risks derived from the literature, as a list may encourage them to cite more risks independent of their importance or prevalence, and (2) using an open-ended interview instrument to let each manager build a list of risks salient to them. In this exploratory study, we err toward an open-ended interview instrument to identify risks. In early-stage empirical research, this approach helps avoid biasing results toward risks that have been identified in the literature.

As with any interview work, this data collection relies on the openness and knowledge of the respondent. To preserve openness, we do not probe their core business model (e.g., supplier names), which can lead to apprehension. We also sequence our questions to avoid giving any impression that we want to buy equipment, which was an issue in piloting. To balance openness and knowledge concerns, we ask questions to check a manager's awareness of finances at the end of the interview. Two of the 60 respondents could not answer the awareness check, which could mean underappreciating financial risk (omitting their responses, the results are qualitatively unchanged). As well, to avoid any speculation, we only ask basic questions to managers about their suppliers, customers, and partners. As such, we do not indirectly capture suppliers’, customers’, and partners’ important perspectives on risk.

The interview takes 40–60 min to complete, including momentary interruptions when customers arrive. The interviews are administered in French, Wolof, or Pulaar by the researchers and translators. All answers are recorded on Qualtrics, an electronic survey platform. Open-ended answers were recorded in short-hand and edited by two researchers after the interview. Of the 53 questions, on average, 1.4% of answers (or 0.7 of 53) were not recorded; 0.9% (or 0.5 of 53) were declined; and 0.7% (or 0.4 of 53) could not be answered. This study was approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology internal review board (#1805389213) and by the Senegalese Ministère de L'Enseignement Supérieur (# 00015052).

3.6 Constructs for data collection and analysis

An activity is the work a firm undertakes to achieve a business objective and is our unit of analysis. It is a common way of organizing the work that happens within one firm (e.g., Alcácer & Delgado, 2016). For this study, we have two possible activities that map to the key pieces of irrigation equipment; one activity is sourcing, stocking, and selling irrigation pumps, and the other is doing so for irrigation pipes. The activity lets us explore factors that may differ between two activities in one firm (i.e., supplier type) and examine the presence of risk in the network at the most granular level possible. One alternative unit of analysis is the firm, which is intuitive but offers no clear way to present results for firms that do both activities.

For each activity, a firm faces risks, our first outcome of interest. We use three principles in the supply chain risk literature to organize our analysis. The first principle is to distinguish risk as operational or disruptive. Tang (2006) defines operational risk, or nominal risk, as the day-to-day uncertainty in the supply chain. Disruptive risk is the uncertainty of large unexpected events such as factory fires. The second principle is to differentiate risk by the source of uncertainty: for example, there is a quality risk, quantity risk, and contractual risk, the latter being a topic of interest in emerging economies (e.g., Shou et al., 2016). The third principle groups risks based on their impact. Financial risk in a supply chain can be understood as a possible inability to profit. Reputational risk is damage to brand and relationships and is also of interest in emerging economies (e.g., Chen & Lee, 2017).

In facing a risk, firms use management strategies, our second outcome of interest. We organize our analysis of strategies along two lines. The first is whether a strategy is an anticipatory effort. Proactive management means addressing a risk before it occurs (e.g., Knemeyer et al., 2009). Examples are contracting to manage the quantity and financial risk (e.g., Cachon & Lariviere, 2005) or certifying suppliers to handle quality and reputational risk (e.g., Chen & Lee, 2017). Reactive management means responding to a realized risk. An example of reactive management for quality risk is repairing a pump or pipe when it arrives broken. The second is whether a strategy is a formal effort. Managers enforce informal strategies through norms and personal relations and formal strategies through the law and contracts.

Our explanatory factors are city size, supplier type, firm size, and manager network. First, city size partitions the few large cities of more than 50,000 people from the many small cities, which is a clear differentiator in Senegal and many other least-developed countries (see Supplement Figure S1). Second, supplier type differentiates upstream activities that source from a manufacturer or an exporter abroad from downstream activities that source from a domestic importer or nonimporting distributor. In other words, a broker intermediates the chain for downstream activities. Third, firm size divides big firms with more than three regular employees from small firms that have three or fewer regular employees. Three is the median-size firm in our population, and microenterprises are sometimes defined by three or fewer employees. Finally, the manager network separates Wolof managers, the predominant ethno-linguistic group in Senegal, and other managers, each being approximately half of the sample.

We pick these factors because of their theoretical relevance, which was introduced in Section 2.2. A description of the correlations between factors is available in Supplement Table S2. This study is directed at policymakers who are concerned with identifying characteristics of firms likely exposed to certain risks: to the extent that these factors are correlated with one another, and some are, this means policymakers can use the most politically or practically tractable factor(s) to group and support firms.

3.7 Data coding and cleaning

We coded the answers to the core risk questions after fieldwork. Three researchers did the coding, two of whom did the data collection and one for additional internal validity, who did not. We adopt a grounded theory approach to abstract patterns and assign codes to the open-ended responses without privileging any one explanation of what constitutes risk (management). However, before starting, we agree to use “textbook-like” operations terms, concepts outlined in Sections 2.2 and 3.6, and markers in codes like what (e.g., quality), when (e.g., on arrival), and who (e.g., customers). With this approach, an answer like “demand cannot come so soon and I cannot buy other products as I wait” is coded as “working capital tied in inventory.” Every risk and strategy that managers cite we code, as none were so afield to require omission. Each response was a few pointed sentences, making coding more a rigorous data cleaning exercise rather than a full, inductive, labeling process; as such, we did not code and jointly review a small sample first. We next label the risk codes as being disruptive, quality, or contractual, as well as financial (or not), and the strategy codes as proactive as well as formal (or not).

Agreement between raters is essential to validate the data and is organized and coded consistently. Among other measures, rater agreement can be measured using Cronbach's alpha (Cronbach, 1951), where 1 is perfect agreement or even a simple percent of agreement between raters’ codes (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The initial interrater reliability (IRR) for all coded fields using Cronbach's alpha between coders 1 and 2 was 0.90 (or 79% simple agreement). The final IRR, after discussion, was 1.00. The initial IRR between coder 3 and the existing codes using Cronbach's alpha was 0.94 (or 85% simple agreement). After discussion between 2 and 3, it was 1.00. We equate codes that are effectively identical and use the better descriptor to standardize them. Quotes used in the discussion are edited for tense and person (when the meaning remains unchanged).

3.8 Assumptions

Our design rests on one main assumption about site selection: Firms in the sector are located in capital cities en route to or in irrigated areas. Our key informants supported this assumption. The data suggest that the assumption is generally valid. It is extremely unlikely that there is a further rural component to the chain that we missed: In the 17 least populated cities out of the 35 that we canvased, we identified only four of the 60 firms. This is itself perhaps a finding. It is also unlikely that we missed many firms in other cities en route to the irrigated areas: There is only one city (Touba) that we did not canvas but in which firms cite having suppliers (2% of firms’ suppliers are based there). With hindsight, we would have canvassed it, as it is a large, departmental capital on a national road indirectly leading to an irrigated area. Ultimately, we canvas more and smaller cities than any other study of which we are aware.

Our design also rests on one assumption about respondent identification: Firms typically have advertisements (e.g., signs) if not storefronts, and we will identify firms without advertisements through snowball sampling. We made this assumption based on pilot visits and in consultation with key informants. Of the 60 firms we analyze, crucially including those that we snowball sample, all have signs, advertisements, and/or products on display that would (and did) prompt us to recruit them. The extent of advertising among firms, including at firms working out of warehouses, is perhaps a finding. It also appears that truck-based traders, which is an interesting concept, are relatively few. Firms only cited 3% of suppliers as working out of trucks without fixed storefronts.

Taken together, as a lower bound, the data indicate that we missed 5% of the firms in the sector, the 2% of suppliers in the uncanvassed city and the 3% working out of trucks.

4 RESULTS

We first report the characteristics of the firms and the industry. Then, we report patterns in risks and risk-management strategies by city size, supplier type, firm size, and manager network.

4.1 Industry characteristics

- Composition: Of the 60 firms we analyze, 20 sell both products, 16 sell only pumps, and 24 sell only pipes. Almost all firms are Senegalese-owned. All managers are male. Approximately half the firms are big firms, with more than three employees; a similar fraction of firms are run by Wolof managers. The median age of the firms is 12 years. Two managers completed college, and 19 completed secondary school.

- Policy engagement: Managers identify “only” as “commerçants” rather than key policy actors. Twenty-eight percent of the firms provide advice to customers about irrigation practices. Just 13% of firms work with the government in some way to promote irrigation policies (e.g., farm demonstrations).

- Inventory: The median number of pumps in the on-hand inventory is one, and the median value of the pump inventory-on-hand is $408. The median number of pipe eaches (10 m) on-hand is 4.2, and the median value of the on-hand pipe inventory is $90.

- Firms by type: Hardware firms house most activities (78%). Machining firms and agriculture firms house the remainder. In general, customer types are comparable across shop types, although agriculture shops disproportionally sell to farmers’ associations (88%).

- Firms by city size: Firms are concentrated in the bigger cities. Exactly half the firms that we analyze are located in the five big cities, and the others are located in 15 small cities (out of 30 small cities). This generally aligns with Colenbrander and van Koppen's (2013) study of the Zambian irrigation supply chain, although we do appear to find more activity outside of major cities.

- Activities by supplier: There are fewer upstream activities than downstream ones. Four in 10 activities are upstream, sourcing from manufacturers or exporters abroad, and the remaining are downstream, sourcing from domestic importers or nonimporter wholesalers.

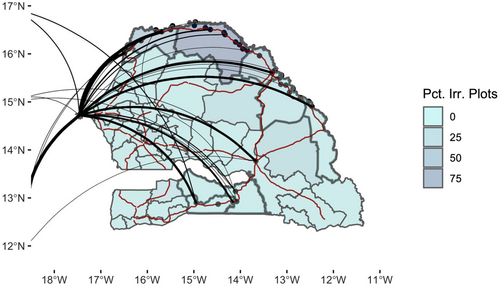

- Suppliers by location: Firms in Dakar intermediate, or broker, downstream firms’ access to manufacturers and international suppliers. Of activities with international suppliers, about one-third of the international suppliers are in China, one-third are in Europe, and one-third are elsewhere. Firms in only five cities in addition to the Dakar order on international suppliers. Of activities with domestic suppliers, just over 90% of suppliers are in Dakar, and the remaining 10% are in four other cities. This pattern is salient when represented spatially as in Figure 3.

- Supplier types by customer types: Farmers and their associations have direct, or disintermediated, access to both upstream and downstream firms. On average, a firm sells to three types of customers (among farmers, associations, other firms, NGOs, and the state). All firms make direct sales to farmers, and two in three firms make direct sales to farmer associations. But, half of the firms also do business-to-business (B2B) irrigation equipment sales. This makes customer type a less helpful way to analytically organize firms, pointing us to use supplier type instead.

Supplier-firm dyads.

Note: In the figure, an arc in the network represents a city-to-city dyad, and all flows are from left to right. The thickness of an arc represents the number of activities in that city-to-city dyad. The interpretation and data sources for other variables are the same as in Figure 2

We summarize these observations in Table 2, which tabulates activities by supplier, customer, and city size. Three results stand out. First, relatively few upstream firms are in small cities, suggesting that upstream firms in big cities intermediate, or broker, chains reach small cities. Second, NGOs source disproportionally from upstream firms, and NGOs and the state source disproportionally in big cities. Third, as noted above, half the activities sell to other firms, so while we do not have visibility on specific activity-to-activity dyads, we do capture firms on both sides of B2B transactions.

| Customer type | City size | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activities | Farmers | Associations | Firms | NGOs | State | Big | Small | |

| Supplier type | Downstream | 49 | 31 | 19 | 4 | 10 | 22 | 27 |

| Upstream | 31 | 24 | 21 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 8 | |

| City size | Small | 35 | 18 | 12 | 1 | 3 | – | – |

| Big | 45 | 37 | 28 | 15 | 19 | – | – | |

- Note: The counts are of activities. For example, 31 activities are downstream and sold to associations.

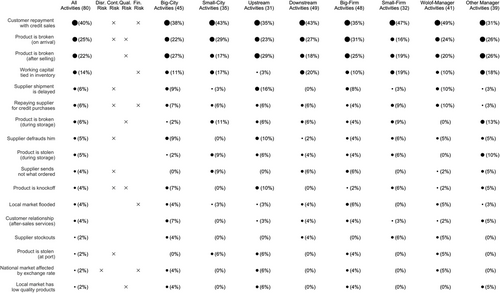

4.2 Supply-chain management risks

What are the risks in the chain? Firms cite 21 distinct risks, with counts of the common ones visualized in Figure 4. The data supporting the figure are available in Supplement Tables S3 and S4. The most common risks are customer repayment with credit sales (32 activities), products being broken on arrival (20) or after selling (18), and working capital being tied in inventory (10). The convergence among many managers on the top 5–10 risks suggests that these are salient aspects of doing business in Senegal. Risks stem from contractual and quality uncertainties and have financial implications as the second set of columns in Figure 4 indicates.

Risks.

Note: In studying this figure, the most revealing comparisons are looking for within-factor differences in counts or percentages (e.g., between big-city and small-city activities). The size of the dot is proportional to the count of activities for which a risk is cited. An X indicates a risk of that type. Risk types are disruption (disr.), contractual (cont.), quality (qual.), and financial (fin.). The percentage adjacent to each dot is the share of the activities experiencing that risk (e.g., share of big-city activities). Only risks cited for two or more activities are presented for readability. The counts in the column headers are the total number of activities used to build the percentages. The full list of risks is in Supplement Table S3

Among contractual risks, nonfeasance and misfeasance are the most common issues that managers report. Nonfeasance is not taking actions that should be taken, such as ensuring quality. Misfeasance is taking inappropriate actions that break a contract, such as suppliers not sending what is ordered. Furthermore, qualitative data suggest that malfeasance, taking actions with an intent to harm such as defrauding, is relatively uncommon in domestic dyads. However, malfeasance appears among upstream transactions, for instance, in long-distance international dyads. One manager explained, “vendors on Alibaba [based in China] used to send me emails about fake Dutch pumps.” Hence, the work of Shou et al. (2016) and Wang et al. (2016) on contract breaches in China addresses an issue that our data confirm is also salient for Senegalese firms, although our data add nuance to contractual risk in suggesting that less deliberate types of it are prevalent within Senegal.

Quality is another major source of risk that managers report, where they detect issues on receipt, during storage, and after selling. In this context, sourcing quality equipment is intertwined with contracting. One manager explained how quality risk percolates through the chain: “When [I buy equipment] in bulk from Dubai, I don't have time to check if every pump works.” That quality after selling is an issue indicates, at best, the unavoidable quality issues in the chain, and, at worst, nonfeasance because this is mostly avoidable. These insights on farm machinery add to the general evidence base around farmers accessing quality goods (e.g., see for farm inputs, Barriga & Fiala, 2020).

The last sets of columns in Figure 4 indicate at a descriptive level the extent to which common risks are prevalent among big-city and small-city activities, as well as other factors.

What factors are associated with risk? City size primarily moderates financial risk exposure across supplier type, firm size, and manager network as reported in brief in Table 3 and in detail in Supplement Table S5. With a Fisher exact test, we evaluate the association of an outcome (i.e., presence of a risk) with a factor (i.e., a city, firm, or manager characteristic). In terms of partitioning activities into those likely exposed to a risk (and not), the factors indicated in Table 3 outperform only using firm size, which Supplement Table S5 confirms in reporting all cross-tabulations and their associated p-values. For further context, we calculate the implied effectiveness of partitioning activities for support (or not) using these salient factors. Relevant to policy-equity concerns, these partitions achieve a low chance of an activity not receiving support despite facing a risk (i.e., Type II error rate). We discuss the results in terms of upstream activities, large firms, and Wolof managers for consistency between the table and text.

| Targeting effectiveness ratios | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk | Characteristic | Risk Not cited | Cited | Fisher exact p | Positive predictive value (PPV) rate | Negative predicative value (NPV) rate | Spec. rate | Type I rate | Sens. rate | Type II rate |

| Activities in all cities | ||||||||||

| Working capital tied in Inventory | Upstream | 30 | 1 | |||||||

| Downstream | 40 | 9* | 0.079 | 18% | 97% | 43% | 57% | 90% | 10% | |

| Supplier shipment is Delayed | Upstream | 26 | 5*** | 0.007 | 16% | 100% | 65% | 35% | 100% | 0% |

| Downstream | 49 | 0 | ||||||||

| Product is broken (during storage) | Wolof manager | 41 | 0 | |||||||

| Other manager | 34 | 5** | 0.024 | 13% | 100% | 55% | 45% | 100% | 0% | |

| Activities in big cities | ||||||||||

| Customer repayment with credit sales | Wolof manager | 13 | 13* | 0.065 | 50% | 79% | 54% | 46% | 76% | 24% |

| Other manager | 15 | 4 | ||||||||

| Working capital tied in Inventory | Upstream | 23 | 0 | |||||||

| Downstream | 18 | 4** | 0.049 | 18% | 100% | 56% | 44% | 100% | 0% | |

| Repaying supplier for credit purchases | Big firm | 33 | 0 | |||||||

| Small firm | 9 | 3** | 0.016 | 25% | 100% | 79% | 21% | 100% | 0% | |

| Activities in small cities | ||||||||||

| Working capital tied in Inventory | Big firm | 15 | 0 | |||||||

| Small firm | 14 | 6** | 0.027 | 30% | 100% | 52% | 48% | 100% | 0% | |

| Repaying supplier for credit purchases | Upstream | 6 | 2** | 0.047 | 25% | 100% | 82% | 18% | 100% | 0% |

| Downstream | 27 | 0 | ||||||||

- Note: Significance from Fisher's exact test marked a more skewed outcome for readability. See Supplement Table S5 for details on the Fisher exact test and all cross-tabulations, as this table only presents cross-tabulations with a Fisher exact p-value of < 0.1. For the effectiveness panel, we assume support is delivered to the grouping that in absolute terms experiences a risk most, which is highlighted in gray for readability. We report six standard measures of effectiveness. The null hypothesis underpinning the effectiveness ratios is that an activity is not risky. There are four outcomes: the activity faces the risk or not and gets support or not. PPV is the chance of facing the risk among those who receive support. NPV is the chance of not facing the risk among those who do not receive support. Specificity (Spec.) is the chance of not getting support among those who do not face the risk; Type I error is one minus that. Sensitivity (Sens.) is the chance of receiving support among those facing the risk; Type II error is one minus that.

- ***p < 0.01; **p < 0.05; *p < 0.1.

With respect to supplier type, the risk associated with working capital is less prevalent in upstream activities than in downstream activities (p = 0.08), especially if they are in large cities (p = 0.05). This may be because upstream activities, compared to downstream activities, are also associated with a broader customer base and thus enjoy more pooled demand, and in bigger cities, this pooling is especially present. A different pattern exists for repaying suppliers for credit purchases, with upstream activities being positively associated in smaller cities with supplier repayment issues (p = 0.05).

Large firms are less exposed to financial risks as compared to small firms. The risk of working capital tied in inventory is significantly less associated with large firms as compared to small firms in small cities (p = 0.03), possibly because of more stable demand or better inventory planning. As one manager explains the concern, “I have to have other investments. I do not spend money on pumps only.” The consequence, another notes, is, “I run out of money to buy [other] stock because it is in inventory.” The issue of repaying suppliers for credit purchases is also significantly less associated with larger firms as compared to small firms in big cities (p = 0.02), perhaps because larger firms have other credit access in big cities.

Wolof managers, those making up the majority ethno-linguistic group in Senegal, are exposed to greater risks of customer nonrepayment, compared to managers of other ethnicities, especially in large cities (p = 0.07). Farmers in the irrigated areas are mainly from ethnic minorities. It is possible that the Wolof managers in big cities are missing social ties with customers that managers of any ethnicity in smaller cities near farms have, as well as the ethnic ties with customers that managers of minority ethnicities in large cities have.

Across all factors, quality risks, while burdensome in the chain, do not vary significantly. This fact is perhaps not surprising, as faulty equipment may be an equally unpredictable problem across all activities. However, it could also have been true that upstream firms unable to quality check far-away suppliers would disproportionally face quality risk, and at the descriptive level, the data do point to this.

Finally, most textbook operational risks are perhaps delayed shipments. All of the firms citing shipment delays are upstream compared to downstream; these upstream firms are likely sourcing from far-away suppliers, which results in correlating supplier type and delay in the network (p = 0.01). Nevertheless, at a descriptive level, in small cities, delays are also an issue. “When I place an order—-it takes 1 day only. The route is good. But, if rain comes, I make the truck go [3 days via] Tamba or Orou because the road holds up better.”

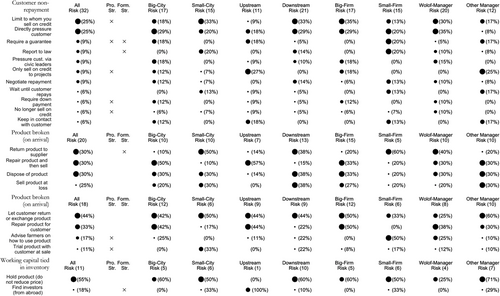

4.3 Supply-chain management strategies

What strategies do managers use? Firms cite 48 distinct strategies to manage the risks; we visualize the most cited ones for the more common risks in Figure 5. The data supporting the figure are available in Supplement Tables S6 and S7. The heterogeneity in strategies for the same risk may imply that there is no standard approach to risk management, with each manager pulling levers available to them due to their city, firm, personal, and other characteristics.

The majority (60%) of risk management strategies used in the supply chain are reactive, which is seen in Figure 5 for the more common risks. Indeed, there is no proactive strategy for 19 out of 20 activities at risk for products being broken on arrival and none to handle supplier delays or the pressure of repaying suppliers for credit purchases. This is detailed in Supplement Table S8. A probable consequence of reactive management is the burden on managers in terms of costs and time. One explanation for the reliance on reactive strategies is that proactive strategies require more enforcement and usually bargaining, which is difficult if firms hold little power relative to customers and suppliers (e.g., Cachon & Lariviere, 2005).2 For instance, with proactive coordination, parties may need to agree to compensate the downstream party for unsold inventory.

We also observe more informal (87%) than formal strategies, which is of interest in both political science and operations management (see, An et al., 2015; Shou et al., 2016). Few firms cite using the law as a way of managing risk. For example, relationship-based strategies are predominant for handling credit risks. One manager begins informally before escalating to a more formal strategy to deal with customer credit issues: “I call three times. Then, go to the police or head of district—but not courts.” Another, in the very worst case, explains, “I go to the village and see the Imam of the mosque.”

The last sets of columns in Figure 5 indicate at a descriptive level the extent to which common strategies are prevalent among risks cited for big-city and small-city activities, as well as other factors.

What factors are associated with proactive strategies? We look in particular to understand the use of proactive strategies because in coordinating the chain they can preserve managers’ time and cost. However, looking across city sizes, supplier types, firm sizes, and manager networks, there are no significantly more proactive than reactive strategies. This is seen in detail in Supplement Table S8. In other words, managers in a range of situations work with comparably reactive toolboxes.

City size specifically does not moderate strategy type, somewhat counterintuitively. Among possible outcomes, it could have been the case that firms in large cities would have used more proactive strategies because of the leverage in bargaining and enforcement that comes with more direct access to technology, institutions, or sales volume, among other likely advantages of operating in a major city. At a descriptive level, managers in small cities do appear to work with a different toolbox, although not a significantly more reactive one. One manager reflecting on quality risk notes, “After-sales service when it breaks is difficult here because Tamba is a remote place with few qualified technicians.” Another talking about local customers repaying him on credit says, “The best option is to stay patient and know they will pay back eventually. I need to keep goodwill with the farmers because that is my customer base.”

5 DISCUSSION

The field study offers some of the first empirical, systematic evidence about the challenges and innovative management strategies of smaller firms in sub-Saharan Africa, focusing on risks at firms that link farmers to large and often foreign irrigation equipment companies. To guide future work, we connect findings to ongoing research streams, new questions, and steps the Senegalese government, donors, and nonprofits could take in practice.

5.1 Implications for research

Our contribution to the operations literature is fourfold. First, we offer the first comprehensive, empirical analysis in the operations literature of the supply chain for agricultural equipment in a less developed economy. The chain does not serve most small cities (15 of 30). Second, managers face primarily contractual and quality risks with financial implications. Third, in contrast to ubiquitous quality risks, financial risks are associated with supplier type, firm size, and/or manager ethnicity, and these relationships are moderated by city size. Fourth, managers creatively, although reactively (60% of strategies) and informally (87) manage risk, indicating an opportunity to coordinate the chain to better manage risk.

The supply chain extends well past large cities but not to 15 of the 30 small cities in Senegal that we study, depriving farmers of ready access to equipment. For the 15 small cities that are part of this supply chain, their firms' source equipment from upstream firms located in the big cities, which intermediate, or broker, the chain. This finding is among the first empirical characterizations of the private-sector last-mile problem, which is extremely difficult to document from a data perspective. This finding raises the possibility that the reach of other chains carrying comparably sized, valued, and sourced goods may be similarly limited, such as those conveying health and livelihood products. To the extent that risks and constraints impede firms from participating in a chain, our results on risk are instructive for policymakers who aim to deliver support to extend chains to unserved areas.

A significant research opportunity is to identify interventions that extend these chains. What empirically is the rural reach of supply chains of similar products in other sectors? The counterfactual empirical question to ours would be why, in terms of risk, do firms in some cities not participate in a chain? Using analytical (experimental) approaches, what forms of support could (do) address the risk to the point of inducing firms to participate in the chain? One specific idea that emerges from our work is NGOs and the state disproportionally source in big cities: to the degree that there is an economic policy interest in diversifying where procurement occurs, how can they support firms to successfully source in small cities?

Day-to-day quality and contractual risks with financial implications, not disruptive risk, are salient to managers. On its own, this finding is important because of the few studies that systematically account for supply chain challenges in lower-income economies. Our observation about the importance of quality risk aligns with Amoako-Gyampah & Boye's (2001) investigation of upstream firms in Accra, Ghana; reinforcing quality is a priority challenge in this context. We compare our findings to theirs in Supplement Figure S2. Our result on the prevalence of contractual risk is consistent with the focus of the supply chain literature on emerging markets (see Shou et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016), although we report two nuances about this risk in Senegal: contractual breaches are generally not based on deceit, and while the contractual risk is related to the manager network, as in China, city size, firm size, and supplier type also play a role in Senegal.

The importance of day-to-day risks is especially relevant for research and practice because it suggests that this risk landscape differs from high-income countries. Disruptive risks are cited for only 3% of activities in our sample, in contrast with APICS (2015) and Deloitte (2013) supply chain management surveys in (mostly) higher-income economies that report varieties of disruption risk as the most cited by managers. We compare our findings to theirs in Supplement Figure S2.

A need then is for research to identify how to mitigate day-to-day quality and contractual risk, perhaps starting with customers not repaying credit sales (32 activities) and products broken on arrival (20) and after sales (18). In doing so, it may be fruitful to consider other (divergent) perspectives in the chain. Building on development research, for farmers, far-upstream firms, and public agencies, which of the firms’ risks are most problematic? What do models suggest about risks’ consequences? One idea that emerges from our findings is that quality risks are commonplace and supplier certification is a potential remedy, but what is a fair and competitive way to push information about certified suppliers, which benefits certified firms, down the chain and to small cities?

Financial risks are moderated by city size, alongside supplier type, firm size, and manager ethnicity. That risk varies with supplier type is long understood but that risk may be sensitive to a firm's location is a less common observation, as high-income countries on which operations literature is based have more homogeneous financial, legal, and built environments (though see Gray et al., 2011). By borrowing factors from the agricultural policy and political science literature, which have been working longer to understand commercial and public decision-making in countries like Senegal, our finding offers new analytical leverage in supply chain work. Taken together, one problem with clear trade-offs that emerges is that a decision-maker, in grouping firms by factors that indicate probable exposure to risk, must balance over- and underinclusively targeting support. This parallels Iyer and Palsule-Desai's (2019) work on (risk-insensitive) criteria for manufacturers to identify “suitable” intermediaries between themselves and very small firms in India.

A major opportunity for research then is to account for how city size moderates risk exposure, in order to recommend how support should be targeted. There remain fundamental empirical questions, such as exploiting the exogeneity in a change in a factor over time and/or firms, like a change in manager, to estimate its effect on risk exposure. An actionable investigation concerns how to target support to firms using these factors. What degree of error in targeting support is acceptable or optimal, a question answered by Verme and Gigliarano (2019) in the humanitarian context? Are there helpful spillovers to unsupported firms sharing a city or supplier with supported firms?

Managers rely more on reactive (60%) than proactive strategies across the board. This is an important distinction for empirically grounded research to build on, as it suggests an opportunity for research and action on supplier and customer coordination. We also primarily observe informal strategies (87%) underpinned often by social ties. The relationship-centric risk-management landscape in Senegal does have similarities with that of high-income countries, seen cited by managers in the PWC (2013) and Deloitte (2013) surveys. We compare our results with those of the surveys in Supplement Figure S3. That interfirm relationships matter is of course globally true, but this fact is taken in higher-income economies against a backdrop of contractual enforcement (e.g., Cachon & Lariviere, 2005).

There is a need, then, for empirical research to highlight innovative strategies organic to lower-income economies, especially the few proactive yet informal ones, or for experimental work to evaluate the potential of existing strategies from higher-income ones (see Castañeda et al., 2019). A manager in a 12,000-person city joked about the reliance on proactive inventory strategies popular in high-income countries like Kanban: “We are not Japanese. For us it is God and [our religious leaders].” There is presumably opportunity both in uplifting creative Senegalese strategies and adapting some from abroad.

5.2 Implications for practice

This work has clear implications for government agencies, organizations like the World Bank, and local nonprofits, which shape supply chains that deliver products like agricultural equipment (GoS, 2014, p. 54; USAID, 2013, p. 8). We propose how Senegal and other sub-Saharan African countries with arid river valleys may extend support to smaller firms, which is an open policy debate both in terms of how to target firms and what support to deliver to them (GoS, 2014, p. 48).

First, the information about the network appears to have use in implementing policy, indicating our approach may serve as a template for decision-makers in other countries and industries. Two local NGOs requested sanitized data for additional analyses, with a particular interest in the rural tails of these supply chains. With these data, the NGOs solved tactical problems, such as checking where farmers can buy replacement pipes when they break.

Second, the analysis of risk appears relevant to broader policy questions in Senegal, suggesting that these insights contribute to the debate on support for firms. Summarizing our results, there are several fronts on which agencies can provide support. We observe across all cities that agencies should provide working capital support to downstream activities and help upstream activities with delayed shipments, the latter possibly by certifying timely far-upstream suppliers. In big cities, agencies should help Wolof managers handle customer repayment issues, perhaps by intervening directly to give loans to farmers. Also in big cities, agencies should target downstream activities for working capital issues, possibly by offering salvage contracts for when demand ebbs, and target small firms for help repaying credit to suppliers, potentially by providing working capital financing. Within small cities, agencies should deliver working capital relief to small firms and help upstream activities repay the credit to suppliers. Across all types of activities, there is room to manage quality risk, perhaps by certifying far-upstream suppliers.

We presented this work to two government agencies in Dakar based on feedback-provided maps of firms and lists of their challenges. We conducted additional descriptive analysis on the most common risks to provide practical guidance on how to target support based on the factors most associated with exposure to the most common risks. This guidance is in line with “new” agricultural programs with “careful targeting” and private partners (Jayne et al., 2018).

5.2.1 Finance customers

Customer nonrepayment is the most common risk. A manager notes, “Now we refuse [to sell on credit to] a lot. If 20 come to buy, 15 will be fine, and the others not.” Public and voluntary agencies can provide loans to farmer associations. Manager ethnicity is modestly associated with this risk exposure in big cities (p = 0.065), with Wolof managers in big cities at a disadvantage for customer repayment; to the extent that this risk is driven by weaker ties between majority managers and minority customers, an agency could deliver loans to minority farmers, indirectly supporting firms. A farmer loan program would proactively shift the risk of repayment issues from firms to the lender and may have other positive implications, such as on water usage (Dawande et al., 2013). A loan program fits into Senegal's ongoing effort to aid farmers, which includes weather-indexed insurance and equipment-leasing programs. A follow-on concern, although, is that loans present a risk to farmers when crop yields fall short.

5.2.2 Certify suppliers

The second and third most common risks are related to quality. Agencies could intervene in the chain by certifying far-upstream suppliers and communicating quality information to upstream firms (Chen & Lee, 2017; and agriculture specifically, Coulter & Onumah, 2002). Being upstream is most (though not significantly) associated with being exposed to the risk of products being broken on arrival (p = 0.178). The overall idea of making available quality information is not new in the chain; managers already communicate bad quality to customers. A small-city manager selling to farmers and associations explains, “We tell them it's not good. However, it is up to them to buy or not.” Supplier certification would proactively extend communication about good quality across the chain.

5.2.3 Share inventory risk

Working capital tied up in inventory is the fourth most common risk. Agencies could offer a salvage program in which they buy excess inventory from downstream activities, helping firms stock to meet demand but manage working capital if demand ebbs. Being downstream is associated with working capital risk exposure (p = 0.079), with downstream firms citing the risk compared to upstream ones at a rate of 9:1. One firm already has a salvage agreement with a commercial partner that can be executed if irrigation equipment demand falls. Downstream activities participating in a salvage scheme would proactively shift the risk of tied-up working capital away from the downstream firms toward agencies, which may be in a better position to reallocate excess inventory.

6 CONCLUSION

This field study introduces an operations perspective to the active policy debate over how to support small firms delivering essential products in a country like Senegal, focusing on the risks that firms selling irrigation equipment face. Our findings indicate that firms would benefit from support other than loans targeted to firms based on their size, which is generally how agencies aid firms today. An evidence-driven effort to manage firms’ most common risks would entail financing farmers, certifying suppliers, and transferring inventory risk to public or nonprofit partners. Our results suggest that efforts to mitigate financial risks should be differentially targeted based on city, firm, and manager characteristics, rather than based on firm size, ensuring public resources are directed at firms likely to be in need of support. We draw these conclusions based on a survey of 35 cities in which we interviewed managers from 60 firms selling irrigation equipment, which is unparalleled in the operations literature in terms of its comprehensiveness of an industry, and offers a potential template for future policy and research studies directed at public decision-makers.

ENDNOTES

- 1 See https://www.sec.gouv.sn/actualit%C3%A9/conseil-des-ministres-du-15-juillet-2020. See also https://www.sec.gouv.sn/actualit%C3%A9/conseil-des-ministres-du-22-juillet-2020.

- 2 Uniquely, one manager, to change this power dynamic, started flying to Dubai to source.