Middle East and North Africa: Terrorism and Conflicts

Abstract

During 2002–2018, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) accounted globally for 36.1 per cent of terrorist incidents, 49.3 per cent of terrorist-induced casualties, and 21.4 per cent of conflict deaths. One focus here is to investigate how MENA's terrorist attacks and conflicts compare with those in the world's other six regions during selected periods, drawn from 1970–2018. There is a well-defined shift of terrorism from Latin America, Europe and Central Asia to MENA, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa after 1989. A second focus is to employ panel regressions to contrast the drivers of global terrorism with those of MENA terrorism. Democracy and civil conflicts are main drivers of MENA terrorism, followed by population. Regional peacekeeping can have an ameliorating effect on terrorism by limiting conflict. The Arab Spring and associated regime changes are shown to have ushered in a wave of terrorism in MENA. Policy recommendations conclude the study.

Policy Implications

- During 1970–2018, terrorist attacks have greatly shifted from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and Europe and Central Asia (ECA) to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), South Asia (SAS), and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), so that enhanced counterterrorism vigilance and resources are particularly needed in SAS, SSA, and MENA.

- Two main determinants of domestic and transnational terrorism in MENA have been democracy and the post-Arab Spring era. In MENA, greater democracy has not been a panacea for terrorism, contrary to the beliefs of the George W. Bush administration. The international community must build up the necessary institutional infrastructure to support democracy in the region.

- MENA is plagued by three major civil wars and other insurgencies that foment regional instability, so that international peacekeeping efforts are needed to curtail these conflicts. Given the huge importance of the number of civil conflicts in causing terrorism in the region, such peacekeeping also serves as a counterterrorism measure.

- Neither reduced poverty (low GDP per capita) nor defense spending ameliorates terrorism in MENA so that donor and local countries' policy makers must look beyond foreign aid or increased defense spending to address terrorism.

- Domestic terrorism poses a far-greater and growing threat than transnational terrorism in MENA and worldwide. Efforts to fight domestic terrorism require donor-country partnerships with terrorism-plagued MENA countries. Despite their difficulty, such partnerships must be forged even though domestic terrorism may not pose an immediate threat to the donor's interests at home or on foreign soil.

Since 1989, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has been plagued by growing terrorist attacks and conflicts, fueling significant increases in the region's military expenditure (ME) (Sandler and George, 2016; SIPRI, 2019; Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) 2017, 2019). For instance, MENA's global share of terrorist attacks rose from 9.8 per cent during 1970–1989 to 36.1 per cent during 2002–2018 – see Section 2.1. In this latter period, MENA accounted for 21.4 per cent of global conflict deaths. The political violence and unrest in MENA had negative consequences for other regions stemming from spillover terrorism abroad, foreign direct investment (FDI) losses, disrupted oil exports, reduced economic growth, and large refugee flows. Relatively few studies focus on MENA in terms of its terrorism and conflict. This relative absence of up-to-date terrorism and conflict analyses for MENA is quite surprising because this region has been the birthplace for many notorious terrorist groups (e.g., the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine [PFLP], Black September, Fatah, Abu Nidal Organization, Hezbollah, al-Qaida in Iraq, al-Nusra, al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula [AQAP], and Islamic State [IS]) and has been embroiled in conflicts over the last decades.

In a pathbreaking and related study, Piazza (2007) focuses on the determinants of terrorism in MENA during 1972–2003 and, like the current study, warns that democracy may worsen terrorism in the region. There are, however, many noteworthy distinctions between his article and ours. First, his sample period ended in 2003 well before the start of the Arab Spring in December 2010. Second, for MENA, Piazza (2007) examines the determinants of transnational and total terrorism, while we investigate the determinants of domestic and transnational terrorism. Third, unlike the earlier study, we contrast the drivers of terrorism for a global sample with those for MENA. Fourth, we can highlight these drivers for 2002–2018 for current relevance. Fifth, we include some novel controls as drivers including the post-Arab Spring era, the number of civil conflicts, an economic freedom index, defense spending burdens, and the number of resident religious fundamentalist terrorist groups. The number of civil conflicts is an especially important driver owing to the linkage between terrorism and these conflicts.

From a conflict vantage, consider the following: In recent years, nine of the 20 MENA countries deployed combat forces on their own territory (SIPRI, 2017). In Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, and Tunisia, internal conflicts involved IS, while in Iran, internal conflict concerned Kurdish armed groups (SIPRI, 2017). Currently, Libya, Syria, and Yemen endure civil wars with international interventions from the Middle East, Europe, Russia, and the United States (SIPRI, 2019). Ten MENA countries – Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – participated in one or more of these civil wars during recent years. The tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran, founded on religious and ideological differences, sparked conflicts throughout the region.

Many MENA countries suffered from a so-called ‘resource curse’ that often, but not always, results in low economic growth, authoritarian rule (e.g., Iran, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and UAE), inflationary pressures, or large military burdens.2. Such burdens, as measured by the ratio of military expenditure (ME) to gross domestic product (GDP), stem from a perceived need to protect resource wealth. MENA countries import their defense systems from varied suppliers with the United States, Russia, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and China being the major exporters of arms to the region during 2014–2018 (SIPRI, 2019). Major MENA arms importers include Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Algeria, UAE, and Iraq, in decreasing order.

Because of its regional conflicts, political violence, and vast oil wealth, MENA plays a key role in the prospects for global terrorism, world tranquility, and economic prosperity. An essential purpose of the current paper is to analyze the nature of the terrorist threat originating in the region since 1970 relative to the other six World Bank's (2019) designated regions – South Asia (SAS), Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), Europe and Central Asia (ECA), East Asia and Pacific (EAP), sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and North America (NA) – in terms of their changing shares of terrorist incidents and casualties (i.e., deaths and injuries). Unlike other regions, North America includes just two countries – Canada and the United States. We employ panel regressions to identify the drivers of MENA terrorism and distinguish them from those associated with global terrorism. In so doing, key similarities and differences of these drivers at the global and MENA levels are identified. Another essential purpose is to highlight changes in conflicts by regions over time. Like terrorism, conflicts shifted their primary regional focus to SAS, SSA, and MENA during the post-9/11 era. Because terrorism and civil conflict may occur in tandem, terrorism's regional shifts may mimic conflicts' regional movement (Findley and Young, 2012). Civil conflicts may induce terror attacks, but these attacks seldom cause civil conflicts. On average, terror attacks involve a small number of casualties unlike domestic conflicts.

There are several findings to highlight. First, the large geographic displacement in the venue of terrorism from Latin America and Europe to the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia has significant implications for the practice of counterterrorism in terms of intelligence, international cooperation, conflict aid, and antiterrorism resource prepositioning. Second, there are important differences between the drivers of global and MENA terrorism. The latter is especially bolstered by democracy, civil conflicts, and the post-Arab Spring era. Third, the recent rising share of domestic terrorism is less likely to motivate strong Western countries to provide counterterrorism assistance. Fourth, the changing location of internal conflicts affects refugee flows, resource supplies, and peacekeeping missions. Fifth, by gaining a perspective on MENA terrorism drivers, the global community is better able to decide how best to ameliorate instabilities in the region. Given the importance of conflict as a driver of terrorism, reduced arms exports to MENA may foster great tranquility and reduced terrorism.

Preliminaries

Terrorism is ‘the premeditated use or threat to use violence by individuals or subnational groups to obtain a political or social objective through the intimidation of a large audience beyond that of the immediate victims’ (Enders and Sandler, 2012, p. 4). This definition emphasizes that subnational entities, and not the state, are the terrorists, thereby ruling out state terror. In the above definition, the political motive of perpetrators is an essential ingredient. Without this motive, a tactic such as kidnapping for ransom is a criminal act of extortion rather than a terrorist incident to further or fund a political agenda. The same is true for other modes of attack such as bombings, assassinations, and armed attacks. Another crucial component of terrorism is audience intimidation, intended to mobilize public pressure on the government to concede to terrorists' demands for political change to end the terror campaign. The definition here concurs with those utilized by the two major terrorist event data sets – namely, International Terrorism: Attributes of Terrorist Events (ITERATE) (Mickolus et al., 2019) and Global Terrorism Database (GTD) (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) 2019).

Terrorist attacks can be decomposed into two main categories. Domestic terrorism involves victims and perpetrators whose citizenship is exclusively from the venue country hosting the incident. Moreover, domestic terrorist attacks have consequences for just the host or venue country, its institutions, citizens, and property. For instance, the assassination of a Lebanese official by a Lebanese terrorist to influence local politics is a domestic terrorist attack. Most countries can be self-reliant in addressing domestic terrorist incidents if their governments possess enough resources. Unless there is an eventual spillover of terrorism to neighboring or other countries, domestic antiterrorist policies do not have to involve foreign governments. The key exception is when domestic terrorism presents a clear danger to the host government's stability, which, in turn, affects trade flows, resource supplies, and other interests abroad. In such instances, foreign donor countries may provide a terrorism-plagued country with conflict aid to address domestic terrorism (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2011).

Transnational terrorism constitutes the second kind of terrorism when an attack in one country involves perpetrators, victims, institutions, governments, or citizens from another country. If a terror attack includes perpetrators from the venue country and one or more victims from another country, then the attack is transnational. Transnational incidents may also involve an attack that starts in one country and concludes in another. The coordinated attacks in Paris on 13 November 2015, involving suicide bombers outside a football match in Saint-Denis, armed attacks at the Bataclan Theater, and shootings at cafes and restaurants, are transnational terrorist attacks. The perpetrators were from terrorist cells in Belgium, who crossed a border before and after the attacks. At the Bataclan Theater, victims came from 17 different countries. Moreover, IS, a foreign terrorist group, organized the attack, which had been planned outside of France. In response to the attacks, the French later carried out bombing raids on IS targets in Syria. Thus, the Paris attacks had many international linkages. With transnational terrorism, countries' counterterrorism policies become interdependent. Efforts by the United States and European countries to secure their borders and ports of entry following 9/11 or the 11 March 2004 Madrid commuter train bombings may merely displace future attacks to US and European interests in MENA, where borders may be more porous (Enders and Sandler, 1993, 2006, 2012).

For our comparative investigation of terrorism in MENA and other regions, we focus on three key time periods. In regards to 1970–1989, the initial date closely corresponds to the start of the modern era of transnational terrorism in 1968 when terrorist groups (e.g., PFLP and Black September) staged major terrorist attacks (e.g., transnational skyjackings or the 1972 abduction of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics) in foreign cities to publicize their cause to a global community (Hoffman, 2006). Terrorist groups' transnational strategy was fostered by advances in communication, especially satellite television transmissions in the 1960s. This 1970–1989 time period not only includes the dominance of the leftist terrorists, but also the bloody era of state-sponsorship in the 1980s (Hoffman, 2006). Both the PFLP and the Abu Nidal Organization engaged in prominent state-sponsored terrorist incidents. The second noteworthy period runs from 1990 to 2001 and encompasses the rising prominence of the religious fundamentalist terrorists and the decline of the leftist terrorists (Enders and Sandler, 2000, 2012; Hoffman, 2006; Rapoport, 2004). This period concludes with the four skyjackings on 9/11, leaving almost 3,000 dead and constituting the largest terrorist incident in the modern era. Finally, our third focus period is 2002–2018, which witnesses the dominance of religious fundamentalist terrorists, the continued presence of nationalist terrorists, enhanced post-9/11 border security, and the decline in transnational terrorism (Gaibulloev and Sandler, 2019; Hou et al., 2020). When we present our panel regressions, we focus on just two periods – 1970–2018 and 2002–2018 – to ensure adequate observations to identify significant drivers of domestic and transnational terrorism at the global and MENA levels.

A final preliminary involves the component countries for each of the seven World Bank (2019) regional classifications. These are given in Table 1, along with their regional abbreviation for easy reference.

| East Asia and Pacific (EAP) | ||||

| Australia |

Fiji |

Lao PDR | New Zealand |

Thailand |

| Brunei Darussalam | Indonesia | Malaysia | Papua New Guinea | Timor-Leste |

| Cambodia | Japan | Mongolia | Philippines | Vietnam |

| China | Korea, Rep. | Myanmar | Singapore | |

| Europe and Central Asia (ECA) | ||||

| Albania | Czech Republic | Ireland | Netherlands | Sweden |

| Armenia | Denmark | Italy | Norway | Switzerland |

| Austria | Estonia | Kazakhstan | Poland | Tajikistan |

| Azerbaijan | Finland | Kyrgyz Republic | Portugal | Turkey |

| Belarus | France | Latvia | Romania | Turkmenistan |

| Belgium | Georgia | Lithuania | Russia | Ukraine |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Germany | Luxembourg | Serbia | United Kingdom |

| Bulgaria | Greece | Macedonia | Slovak Republic | Uzbekistan |

| Croatia | Hungary | Moldova | Slovenia | |

| Cyprus | Iceland | Montenegro | Spain | |

| Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) | ||||

| Argentina | Colombia | Guatemala | Mexico | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Belize | Cuba | Guyana | Nicaragua | Uruguay |

| Bolivia | Dominican Republic | Haiti | Panama | Venezuela, RB |

| Brazil | Ecuador | Honduras | Paraguay | |

| Chile | El Salvador | Jamaica | Peru | |

| Middle East and North Africa (MENA) | ||||

| Algeria | Iran | Kuwait | Morocco | Syria |

| Bahrain | Iraq | Lebanon | Oman | Tunisia |

| Djibouti | Israel | Libya | Qatar | United Arab Emirates |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | Jordan | Malta | Saudi Arabia | Yemen, Rep. |

| North America (NA) | ||||

| Canada | United States | |||

| South Asia (SAS) | ||||

| Afghanistan | Bhutan | Nepal | Pakistan | Sri Lanka |

| Bangladesh | India | |||

| Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) | ||||

| Angola | Congo, Dem. Rep. | Guinea | Mauritius | Somalia |

| Benin | Congo, Rep. | Guinea-Bissau | Mozambique | South Africa |

| Botswana | Cote d'Ivoire |

Kenya |

Namibia |

South Sudan |

| Burkina Faso | Equatorial Guinea | Lesotho | Niger | Sudan |

| Burundi | Eritrea | Liberia | Nigeria | Tanzania |

| Cabo Verde | Ethiopia | Madagascar | Rwanda | Togo |

| Cameroon | Gabon | Malawi | Senegal | Uganda |

| Central African Rep. | Gambia, The | Mali | Seychelles | Zambia |

| Chad | Ghana | Mauritania | Sierra Leone | Zimbabwe |

Changing terrorism threat in MENA relative to other regions

To offer some context to our subsequent panel regressions of the determinants of terrorism, we present an overview of terrorism for three essential time periods. This overview involves the regional distribution of terrorist incidents and casualties, along with the changing composition of total terrorism into its domestic and transnational components. Then we turn to the breakdown of conflicts, a key driver of terrorism, for the seven regions of the world and for the countries of MENA.

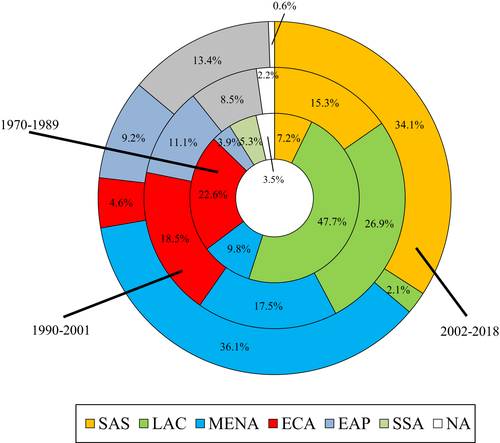

Although Americans have been a prime target of terrorism since 1970, most attacks against US interests take place on foreign soil in terms of transnational terrorism (Gaibulloev and Sandler, 2019). Figure 1 displays the shifting regional distribution of terrorist incidents – domestic and transnational combined – for the three highlighted periods. In moving forward in time, there are some unmistakable patterns in regional venues, revealed by START (2019) GTD event data.3. For simplicity, the percentages, and not the count, of total terrorist attacks for each region in the three periods are shown. Over time, MENA, SAS, and SSA accounted for an increasing percentage of attacks, while LAC, ECA, and NA accounted for a decreasing percentage of attacks. The huge percentage decreases in LAC and ECA are particularly noteworthy in terms of the allocation of counterterrorism resources since 2002. A somewhat mixed pattern applied to EAP. By 2002–2018, just over 70 per cent of terrorism occurred in MENA and SAS combined, with SSA, EAP, and ECA experiencing 13.4 per cent, 9.2 per cent, and 4.6 per cent of incidents, respectively. Just over 2 per cent and less than 1 per cent of incidents took place in LAC and NA, respectively, after 2001. The last percent indicates that the United States must protect its interests against terrorism abroad, especially after its security upgrades following 9/11.

The changing geographical distribution of terrorism was driven by several considerations. The shift of terrorist events to MENA, SAS, and SSA was due to the rise of religious fundamentalist terrorism in Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Nigeria, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Yemen, and elsewhere. In the case of MENA, regional civil wars and the Arab Spring instability reinforced the rise in terrorism. Post-9/11 enhanced security in NA and parts of ECA was also responsible for some of those regional redistributions. Since 1970–1989, the ECA terror decline was also tied to the fall of communism and the reduction in state-sponsorship terrorism, especially in Europe (Enders and Sandler, 1999; Hoffman, 2006). The reduction in leftist and nationalist terrorism in South America drove the falling percentage of attacks in LAC.

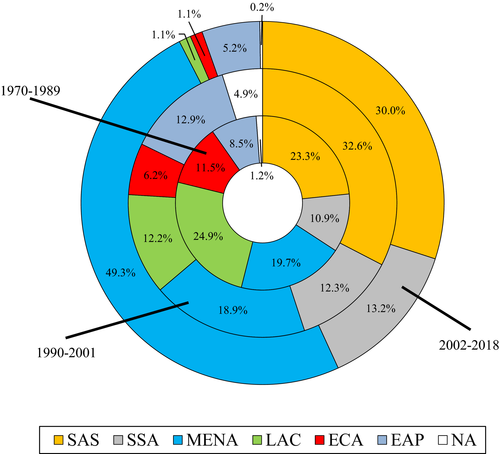

In Figure 2, we decompose terrorism carnage in percentage terms for attacks taking place in the seven regions for the three selected time periods. Percentages of regional casualties are calculated from START (2019) GTD terrorist event data. Understandably, the intertemporal patterns in Figure 2 are like those in Figure 1. As time moves forward, the regional percentages of casualties increased in MENA and SSA, while these percentages decreased in LAC and ECA. For SAS, the earlier pattern from Figure 1 is broken somewhat in Figure 2, where the middle period displayed a slightly greater regional percentage of casualties than for 2002–2018. This slight aberration comes from our use of percentages; SAS casualties increased fourfold from just under 50,000 during 1990–2001 to over 205,000 during 2002–2018. However, the huge increase of casualties in MENA to 337,432 is responsible for the slight fall in SAS's relative percentage of the global total during 2002–2018. The mixed pattern for NA is attributed to the large carnage of 9/11, that is, the 7,423 casualties during 1990–2001 was mostly due to the deaths and injuries from 9/11 in the United States. The pattern for EAP is like that of Figure 1. Generally, the drivers behind Figure 2 as those of Figure 1. During 2002–2018, the regions of most concern are MENA, SAS, and SSA for which MENA accounts for almost half of all terrorist casualties, thus justifying our focus on this region. Almost 80 per cent of all terrorist casualties are in MENA and SAS, thereby providing a clear roadmap for where counterterrorism resources are most needed today.

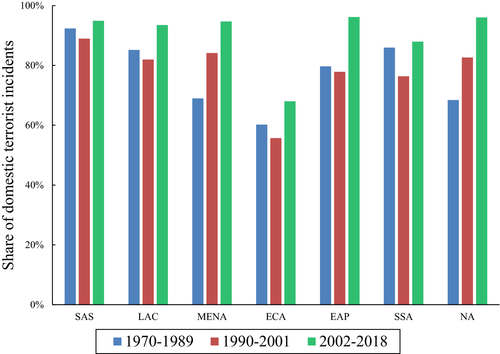

Using the method devised by Enders et al. (2011), we decompose GTD terrorist events into domestic and transnational attacks to offer yet another perspective on terrorism in MENA and the other six regions. As shown in Figure 3, the share of domestic terrorist incidents4. for all seven regions increases from 1990–2001 to 2002–2018 due, in part, to post-9/11 security augmentation. MENA's share of domestic terrorist attacks goes from 69 per cent in 1970–1989 to 95 per cent in 2002–2018 so that only one in twenty attacks involves foreign interests. As such, non-MENA countries may be unmotivated to do much about MENA's recent terrorism given its apparent insular nature, which may be short-sighted if domestic terrorism eventually morphs into transnational terrorism as shown by Enders et al. (2011). By 2002–2018, domestic shares of terrorism in the other six regions were as follows: SAS, 95 per cent; LAC, 93 per cent; ECA, 68 per cent; EAP, 96 per cent; SSA, 88 per cent; and NA, 96 per cent. Those shares underscore that domestic terrorism is the overriding concern in all regions except Europe and Central Asia.5. That concern is bolstered because domestic terrorist incidents display a greater proportion of attacks with casualties than transnational incidents (Gaibulloev and Sandler, 2019; Gaibulloev et al., 2012). Although the international media emphasize the threat of transnational terrorism, this focus is misplaced in recent years as domestic terrorism accounted for the lion's share of attacks. The predominance of domestic terrorism means that donor countries are less motivated to curb terrorism in aid-recipient countries because their resident terrorist groups do not export many incidents or harm much foreign interests on the recipient's soil except in ECA.

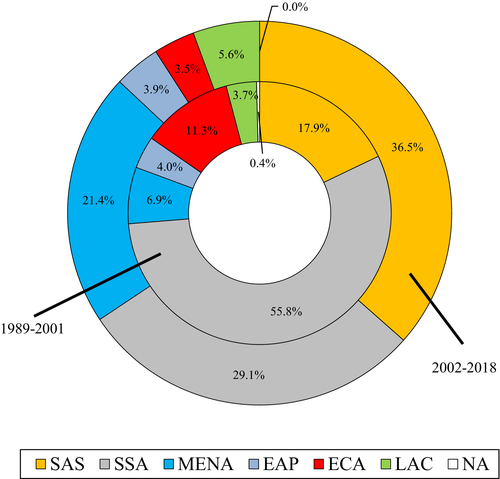

Within-region conflicts are apt to fuel terrorist attacks, particularly domestic terrorism; however, domestic terrorism does not generally fuel domestic conflict. To motivate the importance of conflict as an independent variable in our subsequent regressions, we take a closer look at the regional distribution of conflict deaths for just two intervals – 1989–2001 and 2002–2018 – based on Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) data (Sundberg and Melander, 2013). We remove deaths from Rwanda, which is a huge outlier given its human toll of over half a million. In Figure 4, the regional shares of deaths rose in SAS, MENA, and LAC, while these shares fell in SSA and ECA from the first to second period. The major SSA conflict in the initial period was the war between Ethiopia and Eritrea with 87,692 and 79,452 deaths in 1989–1991 and 1999–2000, respectively.6. Conflicts in Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Sierra Leone, and Somalia also contributed SSA conflict deaths in the pre-2002 period. Although conflict deaths fell in SSA after 2001, this region still accounted for 29.1 per cent of the global total in 2002–2018 when conflicts in Sudan, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Somalia were the main sources of the violence. SAS and MENA are tied to the largest percentage growth in conflict deaths between the two periods. For SAS, conflict deaths during the pre-2002 period came from the Afghan government's engagement with the United Islamic Front for Salvation of Afghanistan, al-Qaida, and the Taliban. Conflict deaths in SAS were also from the Tamil Tigers insurgency in Sri Lanka and the Kashmir insurgency in India in the pre-2002 period. In the ensuing period, SAS's conflict deaths arose from the war and subsequent insurgency in Afghanistan, the insurgency in Sri Lanka, and Taliban-related conflict in Pakistan. MENA conflict deaths came from the Gulf War (1990–1991), Iraq's post-war insurgency, and the Algerian civil war during the initial period, while MENA conflict deaths stemmed from the US-led Iraq invasion (2003), regional civil wars (Libya, Syria, and Yemen), and IS attacks in the subsequent period.

During the most recent period, 87 per cent of conflict deaths were contributed by SAS, SSA, and MENA. By consulting the terrorism-related casualties in Figure 2, we see that those three regions also accounted for the most human toll. This suggests that there is a link between terrorism- and conflict-induced casualties; however, the link is by no means perfect. The connection is greatly blurred when war, but not insurgency, was the main factor behind conflict deaths as in SSA, where the regional percentage of conflict deaths was much greater than that of terrorism-related casualties. Because insurgencies often involve some terrorist tactics, the regional shares for casualties can be more closely tied for conflicts and terrorism.

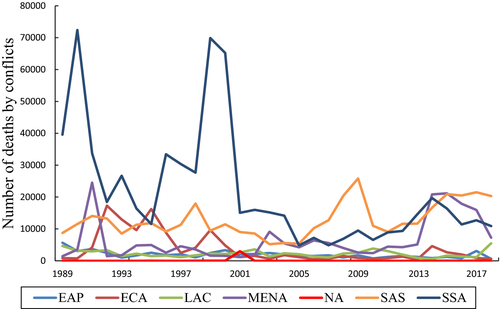

Figure 5 provides an annual perspective of conflict deaths since the start of 1989, based on UCDP data (Sundberg and Melander, 2013). The overall impression is that these conflict deaths were mainly tied to SSA, SAS, and MENA throughout the sample period, with some link to ECA until around 2000. In Figure 5, the two highest SSA peaks were driven by the Ethiopia-Eritrea conflicts. The persistent deaths in MENA since 2014 were because of IS and civil wars in Yemen, Syria, and Libya. Insurgencies in Sri Lanka and Afghanistan were behind recurrent peaks in SAS.

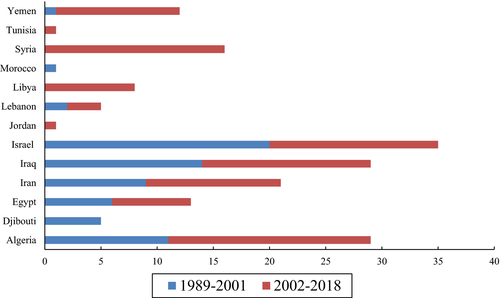

Our last conflict perspective involves the individual MENA countries, 13 of which surpassed the conflict threshold of 25 battle-related deaths once or more times during 1989–2018 based on UCDP/PRIO (International Peace Research Institute, Oslo) Armed Conflict Dataset Version 19.1 (Gleditsch et al., 2002; Pettersson et al., 2019). For the two sample periods, Figure 6 indicates the number of conflicts of a MENA country. Countries with no conflicts are not listed. A country may experience multiple conflicts having the requisite deaths but with different antagonists in a given calendar year, for example, Israel battled both Fatah and Hezbollah in 1990 resulting in two conflicts that year. Throughout 1989–2018, the MENA countries most plagued by conflicts were Israel, Iraq, Algeria, Iran, Syria, and Egypt. For the most conflict-prone countries during the pre-2002 period, the conflict threshold was met or surpassed the following times: 20, Israel; 14, Iraq; 11, Algeria; 9, Iran; 6, Egypt; and 5, Djibouti. During the post-2002 period, the conflict threshold of conflict-ridden MENA countries was met or surpassed as follows: 18, Algeria; 16, Syria; 15, Israel; 15, Iraq; 12, Iran; 11, Yemen; 8, Libya; and 7, Egypt. MENA is a region whose tranquility was disrupted in eight countries by civil wars, insurgencies, or terrorist campaigns since 1989. In addition, conflicts shifted recently to embroil Yemen, Syria, and Libya in civil wars. The Gulf Wars and the Arab Spring have fueled continued regional instability and conflicts, as unintended consequences.

Theoretical and empirical considerations in the study of global and MENA terrorism

Theoretical perspective on the drivers of terrorism

Through a series of panel regressions for 1970–2018 and a recent subperiod, we seek to identify the main determinants of domestic and transnational terrorist incidents for global and MENA samples. In so doing, our dependent variable is either the number of domestic or transnational terrorist attacks for the relevant sample and time periods. There is a rich literature on the determinants of terrorism (e.g., Gaibulloev and Sandler, 2019; Gassebner and Luechinger, 2011; Krieger and Meierrieks, 2011). We draw from this literature to assemble relevant independent variables, commencing with the global analysis before considering MENA.

A country's population (POP) provides more potential targets for terrorist attacks, offers a greater terrorist recruitment pool, and allows for more cover. As such, population is anticipated to exert a positive influence on either domestic or transnational terrorist incidents (e.g., Campos and Gassebner, 2013; Piazza, 2006). As is customary, a log transformation is applied to this variable. The log of gross domestic product per capita (GDP/POP) may have a positive or negative influence on the two forms of terrorism. During the reign of the leftist terrorist up through the early 1990s, a positive influence is predicted because these leftists resided in affluent countries (Abadie, 2006; Piazza, 2006). If, instead, poverty drives terrorism, then a negative relationship between GDP/POP and alternative forms of terrorism is expected. However, the literature usually finds a positive empirical relationship, which is against the conventional poverty argument (Enders et al., 2016; Gassebner and Luechinger, 2011). Democracy is viewed as exerting opposing effects on terrorism. This regime type can facilitate terrorism through strategic considerations including freedoms of movement, association, and privacy. Constraints on the country's executive branch (e.g., preservation of due process) can further foster terrorism. Also, press freedoms can augment terrorism in democracies as terrorists get much-needed visibility (Eubank and Weinberg, 1994; Li, 2005). By contrast, democracy-induced political participation can limit grievances and, thus, terrorism (Eyerman, 1998). By abiding by its mandate to protect lives, democracies can also limit terrorism through swift counterterrorism measures. Autocracies can also take draconian actions against terrorists to curb terrorism. Gaibulloev et al. (2017) argue that these opposing influences mean that highly democratic and highly autocratic states have relatively low levels of terrorism compared to in-between anocratic regimes that have greater difficulty in either protecting lives or assuaging grievances. Anocracies often characterize autocracies that are transitioning to democracy (i.e., some MENA regimes after the Arab Spring) and do not yet have sufficiently functioning bureaucratic institutions. Gaibulloev et al. (2017) predict an inverted U-shaped relationship between regime type and terrorism so that anocracies are most plagued by terrorism (also see Lai, 2007). This relationship can be tested with a quadratic measure of regime type based on a regime index and its squared value.

At the global level, six regions (EAP, ECA, LAC, NA, SAS, and SSA) are anticipated to experience less terrorism than MENA during 1970–2018 as hinted by earlier-presented Figures 1 and 2. The number of civil conflicts should fuel terrorist attacks with a larger positive effect on domestic, relative to transnational, terrorism. As a deterrent, a country's share of GDP devoted to defense is expected to have a negative influence on both kinds of terrorism. If, by contrast, greater defense spending augments grievances with heavy-handed actions, the defense share may be a positive driver of terrorism. Finally, the post-9/11 era should reduce transnational terrorism as borders are tightened; but this era may increase domestic terrorism, especially in hotspots like MENA, as terrorist attacks are not exported.

There are a few necessary adjustments when ascertaining the determinants of MENA terrorism. Given the significant reduction in sample size, we must reduce the number of independent variables to conserve degrees of freedom. Hence, we replace our two measures of democracy with a single measure, Democracy, that distinguishes between democratic and non-democratic states. In so doing, we do not include a regime index and its squared value (described in the following section) to test for a nonlinear relationship. Also, we include a dummy for the post-Arab Spring era of 2010–2018, which we expect increases MENA terrorism. For the MENA estimates, there is obviously no need for regional dummies. In a robustness test, we include the number of religious fundamentalist terrorist groups in the MENA region.

Data

In our global sample for 1970–2018, there are 164 countries that are regionally distributed as follows: 19, EAP; 48, ECA; 23, LAC; 2, NA; 7, SAS; 45, SSA, and 20, MENA. GDP/POP, POP, and Defense shares of GDP are drawn from the World Bank (2019), along with regional classifications. Regime or Polity scores vary from −10 (highly autocratic) to 10 (highly democratic) (Marshall et al., 2018). Polity values below −5 denote autocracies, values 6 and above indicate democracies, and values from −5 to 5 correspond to anocracies.7. The total number of terrorist incidents comes from START (2019) for which we apply the methods of Enders et al. (2011) to distinguish between domestic and transnational attacks. The number of civil conflicts is drawn from UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (Gleditsch et al., 2002; Pettersson et al., 2019). For robustness runs, the number of religious terrorist groups in MENA countries is taken from Hou et al. (2020). A larger number of such groups is anticipated to fuel terrorism, especially at the domestic level. Additionally, we use a measure of economic freedom, which averages five indicators that account for government size, legal system/property rights, sound money, trade freedom, and regulation (The Fraser Institute, 2019). This economic freedom measure is reported from 1970 until 2000 at five-year intervals; thereafter, it is reported annually.

Table 2 indicates our independent variables, their sources, mean values, standard deviation (SD), and minimum (Min) and maximum (Max) values over the panel. By taking the anti-logarithm of population, we derive a mean value of 34.05 million persons for an average country-year. The Min is 0.054 million persons for the Seychelles in 1970 and the Max is 1.392 billion persons for China in 2018. The converted mean for GDP/POP is US$11,107 averaged over all countries and years, with a Min of US$161.7 for Myanmar in 1973 and a Max of US$116,232.8 in UAE in 1980. The mean Defense shares of GDP is 2.79 per cent for the entire sample period, while it is 3.65 per cent, 2.96 per cent, and 1.99 per cent for 1970–1989, 1990–2001, and 2002–2018, respectively, indicating a decline since the end of the Cold War. The average Polity score is 1.41, indicative of an anocracy. For the Democracy dummy, 44 per cent of our sample has a Polity score 6 or higher on average. The regional mean indicates each region's average share of the sample – e.g., EAP accounts for 12 per cent of sample countries during 1970–2018. For sample countries, the average annual number of transnational and domestic terrorist attacks is 1.8 and 13.33, respectively. Germany and the United Kingdom experienced the largest number of transnational attacks of 135 in 1995 and 2013, respectively, while Iraq experienced the greatest number of domestic attacks of 3,098 in 2014. The average number of civil conflicts per country-year was 0.25 with a Max of 7 corresponding to India in 1996, 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2003. Moreover, the average annual number of religious terrorist groups is 0.45 with Pakistan having the most – 27 in 2015. Finally, the mean economic freedom index is 6.08 out of 10 with Singapore displaying the largest index of 8.82 during 1995–1999.

| Count | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ln (Population) | 7957 | 15.86 | 1.65 | 10.89 | 21.06 | World Bank (2019) |

| Ln (GDP per capita) | 6794 | 8.25 | 1.55 | 5.09 | 11.66 | World Bank (2019) |

| Defense shares of GDP | 6161 | 2.79 | 3.33 | 0 | 117.35 | World Bank (2019) |

| Polity score | 6995 | 1.41 | 7.29 | −10 | 10 | Marshall et al. (2018) |

| Democracy | 6995 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 | Marshall et al. (2018) |

| East Asia and Pacific | 8036 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0 | 1 | World Bank (2019) |

| Europe and Central Asia | 8036 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | World Bank (2019) |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 8036 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0 | 1 | World Bank (2019) |

| Middle East and North Africa | 8036 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 | World Bank (2019) |

| North America | 8036 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0 | 1 | World Bank (2019) |

| South Asia | 8036 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0 | 1 | World Bank (2019) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 8036 | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 | World Bank (2019) |

| Num of transnational incidents | 8036 | 1.80 | 7.01 | 0 | 135 | GTD (2019) and Enders et al. (2011) |

| Num of domestic incidents | 8036 | 13.33 | 87.94 | 0 | 3098 | GTD (2019) |

| Num of civil conflicts | 8036 | 0.25 | 0.67 | 0 | 7 | UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset version.19.1 |

| Num of religious groups | 8036 | 0.45 | 1.67 | 0 | 27 | Hou et al. (2020) |

| Economic freedom index | 5188 | 6.08 | 1.90 | 1.84 | 8.82 | The Fraser Institute (2019) |

Empirical methodology

Given that our dependent variable is the count of domestic or transnational terrorist incidents, we must use a regression whose distribution is geared to count data. Options include Poisson or negative binomial (NB) regressions. If there is overdispersion such that the observed variance exceeds the sample mean, then the NB regression is appropriate (Cameron and Trivedi, 2013). When we later test for the underlying distribution in terms of Ln (alpha), overdispersion is confirmed for all our regressions at the .01 level of significance. Thus, we display NB estimates throughout the text and online appendix. Moreover, we report venue-country-clustered robust standard errors.

Results

In Table 3, the NB regressions identify potential determinants for domestic and transnational terrorist incidents for 1970–2018 and 2002–2018. We begin with the results for domestic attacks during the entire sample period. Population has the anticipated positive influence, where a 1 per cent increase in a sample country's population raises the country's expected number of domestic incidents by 0.73 per cent after transforming the coefficient appropriately.8. For the entire period, a 1 per cent increase in GDP per capita augments expected domestic terrorist incidents by 0.20 per cent, which suggests that poverty is not a driver of such attacks. The significant positive coefficient on Polity and the significant negative coefficient on Polity squared are consistent with an inverted U-shaped relationship for which most domestic terrorism occurs in anocracies.9. Next, we consider the influence of the six regional dummies relative to MENA. In the case of EAP, domestic terrorism is 82.5 per cent smaller than that in MENA.10. Domestic terrorism is also significantly smaller in ECA, NA, and SSA by 54.5 per cent, 84.5 per cent, and 64.7 per cent, respectively, compared to MENA. The significant positive coefficient on the Number of civil conflicts means that domestic terrorism increases by about 322 per cent for every additional internal conflict. This represents the expected strong relationship between such conflicts and domestic terrorism, consistent with our overview of such conflicts in Figures 4-6. The Defense shares of GDP has a positive influence where a 1 per cent increase in these shares raises domestic terrorism by 13.2 per cent, so that defense is not having a deterrent effect. Finally, the post-9/11 era does not experience a significant fall in domestic terrorism.

| Domestic incidents | Transnational incidents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970–2018 | 2002–2018 | 1970–2018 | 2002–2018 | |

| Coefficients | Coefficients | Coefficients | Coefficients | |

| Ln (Population) | 0.729*** | 0.717*** | 0.677*** | 0.793*** |

| (0.084) | (0.090) | (0.079) | (0.153) | |

| Ln (GDP per capita) | 0.257** | 0.198 | 0.193* | 0.233 |

| (0.101) | (0.130) | (0.108) | (0.176) | |

| Polity score | 7.042*** | 3.289 | 6.924*** | 7.874*** |

| (2.101) | (3.200) | (1.345) | (2.544) | |

| Polity score squared | −5.810*** | −2.086 | −5.610*** | −5.799*** |

| (1.850) | (2.743) | (1.258) | (2.177) | |

| East Asia and Pacific | −1.743*** | −2.052*** | −1.578*** | −2.222*** |

| (0.505) | (0.681) | (0.344) | (0.449) | |

| Europe and Central Asia | −0.788* | −1.785*** | 0.015 | −0.801** |

| (0.467) | (0.502) | (0.371) | (0.403) | |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 0.327 | −1.935*** | 0.314 | −2.068*** |

| (0.467) | (0.507) | (0.335) | (0.444) | |

| North America | −1.864*** | −2.875*** | −1.398*** | −4.114*** |

| (0.524) | (0.632) | (0.370) | (1.082) | |

| South Asia | 0.282 | 0.819 | −0.545 | 0.020 |

| (0.511) | (0.564) | (0.477) | (0.622) | |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | −1.042*** | −1.213*** | −0.732*** | −0.589** |

| (0.370) | (0.423) | (0.276) | (0.239) | |

| Number of civil conflicts | 1.440*** | 1.673*** | 0.913*** | 0.791*** |

| (0.254) | (0.314) | (0.225) | (0.252) | |

| Defense shares of GDP | 0.124** | 0.150* | 0.078** | 0.193*** |

| (0.057) | (0.081) | (0.037) | (0.058) | |

| Time (2002–2018) | −0.100 | −0.905*** | ||

| (0.206) | (0.224) | |||

| Constant | −14.142*** | −12.704*** | −13.912*** | −17.451*** |

| (1.678) | (2.043) | (1.812) | (3.758) | |

| Ln (alpha) | 1.641*** | 1.576*** | 1.279*** | 1.463*** |

| (0.073) | (0.094) | (0.087) | (0.188) | |

| N | 5,613 | 2,364 | 5,613 | 2,364 |

Notes:

- Cluster-robust standard errors based on country are in the parentheses.

- * p < 0.1,

- ** p < 0.05, and

- *** p < 0.01.

Next, we consider domestic terrorism estimates for 2002–2018. Domestic terrorism is still positively correlated with Population. However, income per capita and regime type are no longer significant determinants of domestic attacks in this much-abbreviated period. Five of the six regions – the exception being SAS – experience significantly less domestic terrorism than MENA, consistent with Figures 1 and 2. The Number of civil conflicts greatly raises domestic terrorism for which an additional conflict increases this terrorism by 432.8 per cent. Finally, Defense shares of GDP only marginally increases domestic terrorism.

We now consider the drivers of transnational terrorist incidents for 1970–2018. Generally, the estimates are like those for domestic terrorism for this period. Population, GDP per capita, Number of civil conflicts, and Defense shares of GDP are positive influences on transnational attacks. Also, most transnational terrorism is associated with anocracies. EAP, NA, and SSA display significantly fewer transnational terrorist incidents relative to MENA. The Number of civil conflicts is a smaller positive determinant of transnational terrorism attacks – one additional internal conflict raises terrorism by 149.2 per cent – which is less than half the influence on domestic terrorism during 1970–2018. Some consequences of these conflicts arise owing to cross-border concerns and international intervention. Another notable difference is that transnational terrorism greatly falls during the post-9/11 era, where the −0.905 coefficient is consistent with a 59.6 per cent drop, which likely stems from more secure borders.

For 2002–2018, the determinants of transnational terrorism are quite like those for the entire period, except where noted. Now five of the six regions display less transnational terrorism relative to MENA, thereby highlighting the key post-9/11 role that MENA plays as a driver of transnational terrorism. The Number of civil conflicts displays a much diminished, but still important, influence on transnational, relative to domestic, terrorism.

In Table 4, overdispersion is again detected so that our four sets of estimates for the MENA sample apply the NB estimator. As explained earlier, there are fewer independent variables for the MENA runs. For 1970–2018, domestic terrorism rises with increases in Population, democratic regimes, the Number of civil conflicts, and the post-9/11 era. MENA's democracies have almost four times as much domestic terrorism as their non-democratic counterparts.11. Since 2002, Iraq, Lebanon, and Tunisia moved from anocracy to democracy, while Egypt, Libya, and Morocco moved from autocracy to anocracy. Six of 20 MENA countries became more democratic. Algeria, Djibouti, Jordan, and Yemen stayed anocracies. Israel maintained its democracy, while the other MENA countries are autocracies. Transitioning regimes are particularly prone to terrorism. Based on the empirical findings in Table 4, the policy of encouraging democracies in this region was clearly unwise in regard to domestic terrorism. Internal wars have a large effect on domestic terrorism – one additional war increases the number of domestic terrorist incidents by almost nine-fold. The post-9/11 era sustains 2.48 times as many domestic attacks as the pre-9/11 period. The Defense shares of GDP has the anticipated deterrent effect.

| Domestic incidents | Transnational incidents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970–2018 | 2002–2018 | 1970–2018 | 2002–2018 | |

| Coefficients | Coefficients | Coefficients | Coefficients | |

| Ln (Population) | 0.511*** | 0.493** | 0.299* | 0.291 |

| (0.165) | (0.245) | (0.178) | (0.204) | |

| Ln (GDP per capita) | 0.324 | 0.268 | −0.023 | −0.074 |

| (0.394) | (0.440) | (0.245) | (0.299) | |

| Democracy | 1.603*** | 2.124*** | 0.837* | 1.356*** |

| (0.460) | (0.402) | (0.474) | (0.481) | |

| Number of civil conflicts | 2.278*** | 2.715*** | 0.942** | 1.186*** |

| (0.599) | (0.539) | (0.390) | (0.398) | |

| Defense shares of GDP | −0.105** | 0.018 | −0.019 | 0.153** |

| (0.053) | (0.085) | (0.049) | (0.068) | |

| Time (2002–2018) | 1.247** | 0.366 | ||

| (0.511) | (0.490) | |||

| Time (2010–2018) | 3.202*** | 0.871** | ||

| (0.464) | (0.353) | |||

| Constant | −10.237** | −11.658* | −4.959 | −5.723 |

| (5.041) | (7.050) | (4.444) | (5.490) | |

| Ln (alpha) | 1.828*** | 1.315*** | 1.325*** | 1.029*** |

| (0.245) | (0.211) | (0.269) | (0.268) | |

| N | 594 | 254 | 594 | 254 |

Notes:

- Cluster-robust standard errors based on country are in the parentheses.

- * p < 0.1,

- ** p < 0.05, and

- *** p < 0.01.

For 2002–2018, the drivers of domestic terrorism in MENA are analogous to those for the entire period, except for defense spending and the Arab Spring. The influence of Democracy on domestic terrorism rises sharply from 396.8 per cent to 736.5 per cent relative to non-democratic regimes when the entire period is compared to 2002–2018. The Arab Spring era experiences a huge increase in domestic terrorism of 2,358.2 per cent. The negative influence of democracy on domestic terrorism is due to some fledgling democracies that do not possess strong bureaucracies to support governance or to address grievances (Gaibulloev et al., 2017).

For transnational terrorism, there are a few noteworthy differences compared to corresponding MENA estimates for domestic terrorism. Internal wars drive transnational terrorism but at a much lower rate than domestic terrorism for corresponding periods. Population is only marginally significant in inducing more transnational attacks during 1970–2018. Democracy still encourages transnational terrorism but at a reduced rate of 130.9 per cent (at the 0.10 level) and 288.1 per cent during 1970–2018 and 2002–2018, respectively. Defense spending positively affects transnational terrorism during 2002–2018. The effect of the Arab Spring is a much-reduced rate of 138.9 per cent for transnational terrorism, compared to domestic terrorism.

Robustness

In the online appendix, we provide 16 sets of robustness runs. In Table A1, we display robustness runs for domestic or transnational terrorism for the global sample, where we include two new variables – Economic freedom index and Number of religious groups. By promoting trade, property rights, and deregulation, economic freedom is expected to promote prosperity and reduce grievances, thereby curtailing both forms of terrorism (Basuchoudhary and Shughart, 2010). In contrast, the prevalence of religious fundamentalist terrorist groups is anticipated to increase both types of terrorism. Because panel data on religious terrorist groups are only available until 2016, we must truncate the estimates by two years. Qualitatively, the coefficient estimates in Table A1 are amazingly consistent with those of analogous variables in Table 3. For the global sample, only the Number of religious groups displays the anticipated positive influence on transnational terrorism for 1970–2016. Economic freedom does not show any significant impact.

Table A2 augments our four MENA runs to include the economic freedom and religious groups variables. Key independent variables – Democracy, Number of civil conflicts, and the Arab Spring era – provide similar findings to those in Table 4. A noteworthy difference is that internal wars have a smaller, but still significant, positive impact on the two forms of terrorism for the sample periods. In addition, the Arab Spring era is only a significant inducer of domestic terrorism in MENA. Economic freedom now has the predicted negative and significant effect on domestic terrorism. Moreover, the prevalence of religious terrorist groups increases domestic and transnational terrorism in MENA for both sample periods, which is notably different than for the global sample.

For a global sample, another set of robustness checks, reported in online Table A3, investigates the determinants of domestic and transnational terrorist incidents for two earlier periods: 1970–1989 and 1990–2001. During the earlier intervals, both types of terrorism still indicate a significant positive response to population and internal conflicts. Once again, an inverted U-shaped response characterizes regime type with anocracies attracting the most terrorism. Given the prevalence of terrorism in LAC and ECA during 1970–1989 (see Figures 1 and 2), the larger response in these two regions relative to MENA is to be expected. For the brief 1990–2001 period, population and internal conflicts continue to be positive drivers of both forms of terrorism. The regime type is not a significant influence probably due to the period's brevity. Domestic terrorism in EAP and NA fall relative to that in MENA. For transnational terrorism, NA attacks decline greatly compared to MENA, while LAC attacks rise relative to those in MENA.

Table A4 complements Table 4 as we examine two earlier hotspots for terrorism – LAC and ECA – for the 1970–2001 period. By necessity, we drop the post-2001 time dummies in Table 4 for this new pre-2002 exercise. We again find Population, the Number of civil conflicts, and Defense share of GDP to be robust positive determinants of domestic and transnational terrorism in these two earlier regional hotspots. The noteworthy distinction is that, unlike MENA, Democracy is not a determinant of terrorism in LAC and ECA during 1970–2001.

Concluding remarks and policy implications

Given its strategic location and oil wealth, MENA plays a pivotal role in world stability and economic prosperity. The spillover of terrorism to Europe and North America, coupled with the recent refugee exigency in Europe stemming from three civil wars in MENA, aptly illustrate the region's impact on political stability and violence. The paper's comparative study of terrorism and conflicts in MENA and the other six regions point to the following significant findings. The regional distribution of terrorism is not static but affected by major events (e.g., the rise of religious fundamentalist terrorists after 1990) and policy reactions to these events (e.g., enhanced border security following 9/11). Since 1989, there have been large-scale geographical displacements of terrorism to MENA, SAS, and SSA away from LAC and ECA. For policy purposes, these displacements require repositioning of counterterrorism assets (e.g., intelligence officers, conflict assistance, and commando squads). The analysis here also underscores the rising importance of domestic terrorism over transnational terrorism for all seven regions, especially MENA. With this shifting importance, developed-country donors are less inclined to supply counterterrorism assistance because their assets are not so threatened at home or abroad. This response is probably short-sighted because domestic terrorism is shown elsewhere to induce more transnational terrorism over time as terrorists try to gain more attention after honing their craft (Enders et al., 2011). For 2002–2012, MENA now accounts for almost half of all terrorism casualties, making this region the epicenter of global terrorism. This is an alarming statistic for world security against terrorism. From our country-by-country breakdown, terrorism is mostly prevalent since 2002 in six MENA countries involved in civil wars or confronting insurgencies, thereby pinpointing where any aid against terrorism should flow.

From a conflict viewpoint, SAS, SSA, and MENA now account for the lion's share of conflict deaths worldwide. The correlation between terrorist violence and conflicts strongly suggests that efforts to curb conflicts through reduced arms sales and peacekeeping missions may pay a ‘double dividend’ by also ameliorating terrorism. The geographical distribution of conflicts morphed over time in the same direction as terrorism. Given conflicts in SAS, SSA, and MENA, NATO must contemplate a greater peacekeeping presence in these regions; however, NATO's decreasing coherence under the Trump administration stifles such a change. Currently, the United Nations deployed peacekeepers to Africa and Asia, while NATO dispatched peacekeepers specifically to Iraq and Afghanistan. Even the latter is being drawn down under the current US administration. The three civil wars in Libya, Syria, and Yemen foment regional instability with negative spillovers to Europe. For Syria and Yemen, arms sales by major arms suppliers, including the United States and Russia, foster the carnage. Without greater restraint by these suppliers, total military spending in MENA is poised to rise sharply and may spark future conflicts in this volatile region, fueled by religious hatreds. Actions to assist countries in MENA to develop their own arms industries, which Saudi Arabia and others seek to do, would eliminate current controls by arms suppliers to constrain client nations' hostile actions. This development should be resisted to bolster world peace.

A final policy conclusion is that pushing democracy in MENA is not a useful counterterrorism policy unless there are enhanced efforts to provide supporting infrastructure and institutions, coupled with the elimination of civil conflicts. The introduction of democracy needs to be more gradual and thoughtful.

Notes

Biographies

Wukki Kim is an assistant professor in the Department of Economics and Law at the Korea Military Academy, Seoul, Republic of Korea. He holds the rank of Major in the Korean armed forces and earned his PhD at the University of Texas at Dallas in April 2020. His research interests are in defense economics, peacekeeping, and terrorism.

Todd Sandler is the Vibhooti Shukla Professor of Economics and Political Economy at the University of Texas at Dallas. His research interests include collective action, environmental economics, terrorism, public economics, and defense economics. His most recent book is Terrorism: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Open Research

Data availability statement

Replication files at: https://personal.utdallas.edu/~tms063000/website/downloads.html.