Public mental health facility closures and criminal justice contact in Chicago

Abstract

Research summary

In 2012, Chicago closed half of its public mental health clinics, which provide services to those in need regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay. Critics of the closures argued that they would result in service shortages and divert untreated patients to the criminal justice system. We explore this claim by examining whether and to what extent the closures increased criminal justice contact. Using a difference-in-differences framework, we compare arrests and mental health transports in block groups located within a half mile of clinics that closed to those equidistant from clinics that remained open. While we find evidence that police-initiated mental health transports increased following the closures, we do not observe similar changes in arrests.

Policy implications

Chicago's mental health clinic closures remain a contentious issue to this day. Our results suggest that the shuttered clinics were meeting a need that, when left unmet, created conditions for mental health emergencies. While the closures do not appear to have routed untreated patients to the county jail, they increased police contact and, subsequently, transportation to less specialized emergency care facilities. Our findings demonstrate the need to strengthen health care access, crisis prevention, and the mental health safety net to preclude police from acting as mental health responders of last resort.

With more than a third of inmates diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, Cook County Jail houses one of the largest populations of individuals with mental health conditions in the country (Ford, 2015). While Cook County stands out due to its size, facilities throughout the United States are facing similar situations. Today, jails and prisons house more individuals with serious mental illness than state mental hospitals (Treatment Advocacy Center, 2016). The criminal justice system's current role as mental health provider of last resort has been blamed on the underfunding of mental health services (Kuehn, 2014; Raphael & Stoll, 2013).

In Chicago, where the vast majority of inmates detained in Cook County Jail originate, the controversial closure of half of the city's public mental health clinics in 2012 features prominently in debates around policing (Cherone, 2023). Before the closures, the city operated 12 publicly funded mental health clinics that provided services to people with various conditions at no cost. Under then-Mayor Rahm Emmanuel, the city shuttered six clinics amid state budget cuts following the 2008 recession (Kadner, 2015). Officials cited redundancies as the reason for the closures, referring to them as consolidations that would improve efficiency without reducing the quantity or quality of care (CDPH, 2012; Corley, 2012). But critics pushed back on these claims, pointing to shortages in mental health care in some of the city's most underserved communities (Adams, 2020; Balde & Relerford, 2012; Kadner, 2015). Underlying these concerns was fear that the criminal justice system would fill the void, with mental health advocates and policing experts alike warning that the closures may divert untreated patients to the county jail (O'Shea, 2013). This paper explores these claims and contributes to discussions on the criminal justice implications of reduced access to mental health care.

This study examines whether the clinic closures influenced levels of criminal justice contact. In the absence of regular care, those in need are often directed to call 911, wherein police are dispatched (Watson & Wood, 2017). Upon answering mental health calls or encountering individuals considered a threat to themselves or others, officers generally have one of two options: arrest the individual or send them to a hospital for emergency treatment (Wood et al., 2021). If the closures resulted in mental health issues going untreated, we might anticipate changes in these two types of police interactions. This could occur if police assumed social control responsibilities formerly filled by the clinics or if the closures influenced socially deviant conduct or the risk of victimization near the shuttered clinics. To explore whether the closures affected police contact, we exploit variation in the timing and location of the closures using a difference-in-differences framework that compares block groups within half a mile of shuttered clinics to those equidistant from clinics that remained open. We find evidence that the closures increased mental health transports but not arrests. Thus, while the closures did not funnel individuals to the county jail, they shifted social control responsibilities from mental health clinics to the criminal justice system, ultimately placing police in the position of managing the distribution of patients throughout the city.

This paper expands on research exploring the connection between mental health care access and criminal justice involvement in important ways. Earlier studies have demonstrated that limited access to mental health care heightens the likelihood of incarceration (Frank & McGuire, 2011; Yoon et al., 2013), while improved access reduces the frequency of arrests (Deza et al., 2022; Evans Cuellar et al., 2004). Our study uniquely contributes to this literature by investigating contemporary patterns in this relationship, focusing on the impact of restricted access to public mental health facilities on police interactions within more localized geographies. We examine recent clinic closures and leverage the presence of comparable sites, which allows us to draw conclusions with empirical rigor. Further, by analyzing changes in police-initiated hospital transports in addition to arrest outcomes, we provide a comprehensive understanding of how reductions in mental health services influence these intersystem dynamics.

1 RELATED LITERATURE

One of the most frequently examined explanations for the overrepresentation of persons with mental health disorders in prisons and jails is the underfunding of mental health services (Kuehn, 2014). Beginning in the 1950s, the mental health system began to shift from more institutional forms of care to community mental health centers, resulting in the closure or downsizing of many state mental hospitals (Harcourt, 2011). Yet few community mental health centers were built, which created severe care shortages (Roth, 2018). The most rigorous empirical studies suggest that deinstitutionalization was responsible for small increases in incarceration between 1980 and 2000 (Raphael, 2000; Raphael & Stoll, 2013).

Studies exploring these intersystem dynamics since the 2000s have linked mental health care supply and access to rates of jail and prison confinement. For example, Yoon and Luck (2016) examined trends in jail populations in 44 states between 2001 and 2009 and found that a 10% increase in per capita public inpatient mental health expenditures led to a 1.5% reduction in jail inmates. Using administrative data from South Carolina and a matched difference-in-differences strategy, Jácome (2020) found that men aging out of Medicaid coverage were 15% more likely to be incarcerated. These effects were concentrated among those receiving behavioral health services, suggesting that losing access to mental health care played an important role in explaining this increase. These studies emphasize the importance of public funding for mental health, as insurance and cost are frequent barriers to care.

The connection between mental health care access and incarceration has been explained through a mechanism of increased criminal justice contact, where the absence or presence of personal or community resources to treat mental health conditions affect the relative risk of contact with the justice system (Markowitz, 2006; Yoon & Luck, 2016). Indeed, research has largely converged on the finding that access to mental health services is negatively associated with rates of arrest. In a national-level study, Deza et al. (2022) found that counties with more office-based mental health providers experienced lower rates of juvenile arrest. Yoon et al. (2013) found that declines in inpatient psychiatric hospital beds in King County, Washington increased the likelihood of arrest for minor offenses among persons with severe mental health disorders. In their analysis of youth in the Colorado child welfare system, Evans Cuellar et al. (2004) found that mental health and substance use treatment reduced the likelihood of arrest for all types of criminal offenses. Research on diversion programs has also demonstrated the ability of mental health services to influence criminal justice contact. Evans Cuellar et al. (2006) found that a Texas program diverting youth with mental health disorders to treatment reduced the probability of re-arrest. A more recent study found that a Chicago Police Department (CPD) program connecting individuals with substance use disorders to treatment lowered rates of arrest (Arora & Bencsik, 2021). Thus, improved access to mental health care appears to decrease arrests, while reductions have the opposite effect.

Aside from studies examining the fallout of state mental hospital closures during deinstitutionalization, little empirical work has examined whether the shuttering of public mental health facilities increases exposure to the criminal justice system. Our study seeks to fill this gap. Specifically, we consider whether the closure of Chicago's public mental health clinics—an important component of the mental health safety net—aggravated levels of criminal justice contact in communities already enduring the myriad consequences of systemic disinvestment.

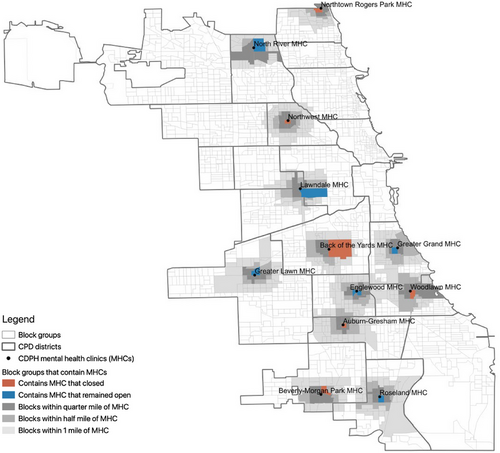

2 BACKGROUND ON THE CLINIC CLOSURES

Before the closures, Chicago operated and funded 12 mental health clinics that provided services to individuals regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay. In 2012, then-Mayor Rahm Emmanuel closed six clinics, most of which were located on the city's south and west sides in majority Black and Latino neighborhoods such as Gresham, Woodlawn, and Back of the Yards (Figure 1). Today, only five public facilities remain after the privatization of the Roseland clinic in 2016 (Black, 2016).

CPD patrol boundary and CDPH mental health clinic locations. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Source: Jurisdictional boundaries were retrieved from the Chicago Police Department, and public mental health clinic locations were obtained from the Chicago Department of Public Health.

The reason for the closures and why specific clinics were targeted remain unclear. City officials cited redundancies and claimed that the closures saved the city $2.2 million, which could be redirected toward other mental health resources (Joravsky, 2013). Officials asserted that the clinics targeted for closure were underutilized (Quinn, 2018), but critics questioned these motives, highlighting a lack of transparency and little public deliberation. Before the closures, city officials estimated that 5200 people were receiving services at the clinics; this dropped to roughly 2800 after the closures (Coen, 2019). While city officials estimated that about 3400 more people received services from other organizations, there was no official tracking of patients, leaving significant uncertainty regarding how many people fell through the cracks.

Nonprofit organizations, providers, patients, and their families emphasized the toll the closures would have on uninsured and economically marginalized residents (Joravsky, 2013). Despite assurances from officials that patients could find care at other clinics, medical staff at these facilities, including therapists and psychiatrists, declined following the closures (Lydersen, 2015). Journalists reported instances of former patients enduring longer and more complicated commutes to access services at other clinics (Coen, 2019). Those transferred to private providers frequently faced long wait times and unaffordable copays once they got in (Black, 2019). For these reasons, critics argue that the closures resulted in the interruption or termination of treatment—a claim corroborated by stories of former patients discontinuing care after the closure of an accessible clinic (Coen, 2019). Some contend that these disruptions left many without treatment and at greater risk of criminal justice contact (Fawcett, 2014). Whether and to what extent these fears were realized remains an open question.

3 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND HYPOTHESES

By reducing access to mental health care, the closures likely resulted in mental health conditions going untreated. Each of the city's public mental health clinics provided outpatient care (i.e., medication management) to those with serious mental illness, and most of the centers offered walk-in services for individuals experiencing psychiatric emergencies (see Table A1). Journalists documented multiple cases of former patients struggling to secure appointments and facing long wait times with other providers (Williams et al., 2008), encountering obstacles accessing alternative facilities (Joravsky, 2014), and ultimately interrupting or discontinuing treatment (Coen, 2019).

By disrupting both routine and emergency mental health treatment, the closures could have affected the frequency of police contact through interrelated institutional and individual channels. Institutionally, the closures may have shifted social control responsibilities from geographically based mental health facilities to the criminal justice system. Without the care previously offered by the clinics, police may have been more likely to respond to symptoms of untreated mental health conditions—thereby increasing police-based remedies like arrest and mental health transport. The absence of clinical care may have also increased socially deviant conduct or the risk of victimization near the clinics—ultimately affecting criminal activity and, by extension, arrests.

Scholars have viewed the mental health and criminal justice systems as alternative institutions of social control for individuals displaying deviant behaviors (Lincoln, 2006; Liska et al., 1999). The interchangeability of these two systems is evident in the convergence of findings demonstrating the inverse relationship between mental health care and criminal justice contact (Deza et al., 2022; Jácome, 2020; Markowitz, 2006; Yoon & Luck, 2016). Yet, while both systems serve social control functions, they interpret and address the symptoms of mental health issues differently. Where mental health providers are more likely to diagnose socially disruptive behavior as a manifestation of untreated mental illness, police tend to see troublesome situations through the lens of their role as law enforcers—which can result in the “criminalization” of mental illness (Lamb et al., 2002; Teplin, 1984). The supplanting of public mental health clinics by law enforcement as institutions of social control may have increased the likelihood of police handling untreated mental health conditions as conflict situations. While arrest is one way officers can address deviant behavior, it is not their only recourse. If an officer sees that an individual is in mental health distress, they may decide to transfer that individual to the hospital. This tends to be a preferred remedy among CPD officers responding to mental health-related calls, especially when an individual shows signs of medication noncompliance—in which case, officers see hospitalization as an opportunity to get individuals back on track (Watson & Wood, 2017). Regardless of the specific response, we would expect the institutional transfer of social control responsibilities from the mental health system to law enforcement after the closures to increase police contact.

Yet a rise in police contact following the closures may not be solely attributable to structural shifts in social control mechanisms but, in part, due to changes in arrest-generating behavior. If the shuttered clinics were a site of routine care for patients, we'd expect crime, and by extension, arrests, to increase when mental health conditions were left untreated. This could occur for different reasons.

First, untreated mental illness might increase the likelihood of socially deviant behavior among those for whom the clinics remained a site of routine activity. These behaviors may emerge from the concurrence of mental health issues and other conditions like homelessness (Evans et al., 2021; Fazel et al., 2009) and substance use (Harris & Edlund, 2005; Swendsen et al., 2010). Qualitative research has shown that Chicago police often encounter individuals experiencing these issues when responding to mental health-related calls (Watson & Wood, 2017; Wood et al., 2017). Individuals with mental illness experiencing homelessness are at increased risk of arrest for public disorder offenses, such as vagrancy, intoxication, or disorderly conduct (Markowitz, 2006). Substance use is also a strong predictor of contact with the criminal justice system among persons with mental illness (Swartz & Lurigio, 2007). Those with mental health issues using substances may be more likely to encounter law enforcement for reasons ranging from impaired judgment to the possession of illicit drugs. Indeed, scholars have found that the relationship between mental illness and crime is largely mediated by substance use (Borum et al., 1997; Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Fazel et al., 2009). Following Cohen and Felsons’ (1979) routine activities theory—which posits that crime occurs when there are suitable targets, likely offenders, and an absence of capable guardians—untreated mental health conditions may affect the pool of offenders engaging in minor crimes, thereby affecting levels of arrest.

Second, untreated mental health conditions could heighten the risk of victimization. Persons with mental illness have higher rates of victimization than the general population (Maniglio, 2009; Teplin et al., 2005) and are notably more likely to become victims of violent crime (Hiday et al., 2002; Latalova et al., 2014). In fact, individuals with mental illness are more often victims of violence rather than perpetrators of it (Choe et al., 2008). Substance use disorders and homelessness only heighten this vulnerability (Maniglio, 2009). That is, in the absence of medical care, individuals experiencing mental health episodes may become more vulnerable crime targets. Applying routine activities theory, changes in suitable targets may influence levels of violent crime and, by extension, arrests.

Given the institutional and individual mechanisms discussed above, we propose competing hypotheses regarding the impact of the closures on police contact. Following the closures, patients may have sought care at the shuttered clinics or continued their routine activities if they lived nearby. If law enforcement assumed a social control role formerly filled by the clinics, we would expect arrests and mental health transports to increase as police respond to the symptoms of untreated mental health conditions. While we are unaware of formal directives issued by CPD after the closures, it is possible that command staff proactively deployed officers to areas near the shuttered clinics, anticipating a rise in disorder problems. Untreated mental health conditions may have caused former clinic patients to exhibit disruptive behavior, resulting in arrests for less serious offenses such as drug possession, trespassing, and petty theft. Additionally, the lack of care could elevate the risk of victimization among former patients, potentially resulting in arrests for violent crimes like robbery, assault, and homicide. However, it is also possible that the closures dispersed rather than congregated individuals with mental health issues. After the closures, individuals may have sought care elsewhere. This shift could decrease or leave unchanged the number of individuals experiencing the symptoms of untreated mental health conditions near the closed facilities. If this occurred, the clinic closures might have the opposite effect, failing to increase mental health transports or arrests. Which of these potential shifts dominate is an empirical question we investigate in our analysis.

4 DATA AND MEASURES

4.1 Criminal justice contact

To measure criminal justice contact, we made a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to CPD for data on all recorded arrests and mental health transports between 2008 and 2016. Using information on the date and location of each incident, we produced block group-level quarterly counts of arrests and mental health transports.1

Arrest totals reflect the number of arrests made by CPD officers in each quarter. A series of offenses committed by one individual may culminate in a single arrest, or a single offense may result in the arrest of more than one person. If two people were arrested for the same offense, we recorded this as two separate arrests. If someone was arrested for more than one offense, we referred to the most serious offense to characterize the arrest using the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Hierarchy Rule (FBI, 2004). We created arrest counts for violent crimes and nonviolent misdemeanors to distinguish different types of criminal behavior possibly associated with the closures.2 Violent crimes consist of homicide, sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and aggravated battery. We classified all remaining offenses as nonviolent and used detail indicating whether the arresting offense was a felony or misdemeanor under the Illinois Criminal Code to identify nonviolent misdemeanors. Most nonviolent misdemeanor arrests were for simple battery (21%), drug-related offenses (20%), criminal trespassing (12%), larceny (11%), and simple assault (5%).

We also produced block group-level quarterly counts of mental health transports. These incidents occur when officers request that a person experiencing a mental health emergency be transported to a mental health intake facility. As of 2002, all CPD officers receive guidance on mental health issues during their preservice academy training (Watson et al., 2010). Part of this training includes guidance on identifying signs and symptoms of mental health conditions and common behaviors associated with individuals in crisis, such as self-injury, extreme emotional responses, statements of harm to self or others, and hallucinations (CPD, 2022, 2023). When an officer encounters someone they believe needs immediate hospitalization to protect themselves or others from physical harm, they may take that person into protective custody and transport them or request they be transported to an intake facility, most of which are hospitals.3

4.2 Mental health clinics

We retrieved data on the city's public mental health clinics (MHCs) from a report published by the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH, 2012). We used this report and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Directories of US Mental Health Facilities to confirm each MHC's location and operating status.4 Figure 1 shows the location of each MHC and block groups within a quarter mile, half a mile, and one mile of the clinics. We exploit this geographic variation by comparing block groups located within walking distance, which we define as a half mile, of MHCs that closed to those equidistant from MHCs that remained open.5 Our analytic sample includes 6552 block group quarter-level observations (182 block groups and 36 quarters).

We focus on block groups within walking distance of MHCs to more precisely target areas served by the facilities. Residents within walking distance of a particular clinic likely seek treatment at that facility. We cannot assume the same for residents living farther away as we lack information on the catchment area of each MHC. Additionally, individuals commuting to the clinics by public transit or other nonactive means may have an easier time transitioning to different locations than those who walk. This is particularly relevant for clinic clientele, including those with a history of trauma, for whom taking public transit may be a triggering experience (Fawcett, 2014), or those with low incomes who may not have access to a car or be able to afford public transit. Methodologically, limiting the spatial buffer improves the comparability of treated and comparison block groups, which reduces confounding and allows for cleaner identification of the closures’ impact.

As shown in Table A1, all MHCs offered services for adults with serious mental illnesses, but the closed MHCs provided a more extensive range of services and programs. A larger proportion of the closed clinics provided treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder, accepted referrals from the criminal justice system, served youth with severe emotional disturbance, treated individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders, and offered walk-in services for individuals experiencing psychiatric emergencies. In only one aspect did the open MHCs surpass the closed clinics, with two-thirds having on-site professionals trained in crisis intervention compared to just one of the closed clinics.

4.3 Sociodemographic, policy, and health provider characteristics

We supplement these data with information on block group sociodemographic characteristics. Using the American Community Survey's 5-year estimates, we collected information on population size, median household income, percent of residents living below the federal poverty line, receiving public assistance, unemployed, under age 18, male between the age of 15 and 24, identifying as Black or Hispanic, the percent of vacant housing units, and the share of nonvacant housing units occupied by owners.

We also collected information on other policies that may confound the impact of the closures. We retrieved data on the location and timing of CPD's rollout of body-worn cameras, which prior research has linked to increased arrests (McCarty et al., 2021). Body-worn camera adoption began in mid-2016 and was active in six CPD districts over our study period. We identified the CPD district encompassing each block by overlaying district and block group boundaries. We do not directly control for CPD's implementation of crisis intervention teams between 2005 and 2006 (Watson, 2010) or its 2018 drug diversion program (Arora & Bencsik, 2021) as their implementation did not overlap with our study period.

To account for potential confounding induced by public and private investment, we collected information from the Chicago Department of Planning and Development on the number of tax increment financing (TIF) projects. Specifically, we retrieved information on redevelopment and intergovernmental agreements approved by the City Council over our study period.

We also retrieved information on other affordable health facilities that may have offset the MHC closures. We first gathered information on affordable mental health facilities. We began by retrieving the complete list of mental health facilities within 25 miles of downtown Chicago operating in 2021 from the SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator.6 We supplemented these data with information on facilities included in the 2008 and 2012−2016 SAMHSA Directories of US Mental Health Facilities. We combined these lists and restricted the facilities to those that accept Medicaid, offer payment assistance, or charge sliding scale fees. We gleaned whether a facility provided services each year based on their presence or absence in the annual directories.7 Using geographic data for each facility, we calculated the number of alternative mental health facilities in each block group and year of our study period. We also collected information on federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). FQHCs are federally funded nonprofit health centers or clinics that serve medically underserved areas. Using geographic data and information on the date HRSA approved the site's application, we calculated the number of FQHCs or FQHC “look-alikes” in each block group per quarter.8 Absent information on when FQHCs closed, we assumed that once a site was approved, it remained open for the remainder of the study period.

4.4 Calls for service and public transit ridership

We also collected information on public transit ridership and calls for police service for use in supplemental analyses. We obtained data on calls for police service through a FOIA request to Chicago's Office of Emergency Management and Communications. We mapped calls onto block groups using the hundredth block address where the call originated. We classified calls as mental health-related if the dispatcher described the event as a mental health disturbance or the responding officer indicated that the call was related to mental health. We also retrieved information on local transit patterns from the Chicago Transportation Authority (CTA) from the Chicago Data Portal. Specifically, we used data on the location of each bus and train (“L”) stop as well as daily ridership totals for every bus and “L” route. We geocoded every CTA bus and “L” stop, placing each in its respective block group and assigned quarterly ridership totals for the routes that pass through block groups with CTA stops. Because CTA could not provide entry and exit totals for every route and stop, we used aggregate route ridership totals to gauge the amount of foot traffic in each block group.

5 EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

We include several controls to account for potential sources of confounding. The time-varying block group-level vector, , adjusts for population size, median household income, and population composition by poverty status, public assistance receipt, unemployment, age, gender, race/ethnicity, housing vacancy and ownership, as well as the presence of affordable mental health facilities. These regressors were available on a yearly basis. Also included in this vector are quarterly block group-level controls for the presence of body-worn cameras, number of TIF projects, and number of FQHCs. We also include fixed effects to account for unobserved, time-invariant block group characteristics () and quarterly systematic time trends () that account for citywide events or policies that affect all block groups in a given quarter and year.

Our two primary outcomes, arrests and mental health transports, are count variables. We model these outcomes using a Poisson fixed effects regression because it is not uncommon for block groups to have zero counts over a three-month period.10 All models were weighted using block group populations in 2008, the first year of our study period, and we clustered standard errors at the block group level. Our parameter of interest, , captures the change in criminal justice contact after the closures in block groups within a half mile of closed MHCs relative to block groups within a half mile of MHCs that remained open.

Equation (2) includes leads and lags to MHC closure, allowing us to examine trends 12 quarters before and after the closures. Any systematic differences between block groups near the closed MHCs and those that remained open before the closures could suggest that factors other than the closures are responsible for changes observed after the closures. This approach helps to dispel concerns regarding the confounding impact of unobserved and unaccounted-for factors by allowing us to gauge if outcomes differed systematically across block groups before the closures and whether there is a break thereafter.

6 RESULTS

6.1 Descriptive evidence

Table 1 displays baseline descriptive statistics for the city and our sample by closure status. Residents living near MHCs tend to earn less, rely more on public assistance, are more likely to identify as Black, are younger, have lower levels of home ownership, and experience higher levels of poverty, unemployment, housing vacancies, TIF investments, and criminal justice contact than the average city resident. When inspecting block group differences by closure status, we see that while arrests for violent crime and mental health transports are similar, block groups proximate to closed MHCs had higher levels of nonviolent misdemeanor arrests, were older, less economically disadvantaged, had fewer males age 15 to 24, more Hispanic residents, fewer Black residents, lower rates of home ownership, less TIF investment, and fewer affordable mental health facilities than block groups near MHCs that remained open.

| Chicago | Block groups w/in 0.5 mi of MHCs | Block groups w/in 0.5 mi of MHCs by closure status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remained open | Closed | ||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p Value | |

| Outcomes | |||||||||

| Violent arrests | 0.54 | 1.04 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.861 |

| Nonviolent misdemeanor arrests | 10.71 | 16.36 | 12.68 | 12.32 | 11.38 | 9.99 | 13.86 | 14.02 | 0.006 |

| Mental health transports | 0.59 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.201 |

| Covariates | |||||||||

| Log population | 7.05 | 0.42 | 6.99 | 0.43 | 6.96 | 0.41 | 7.02 | 0.45 | 0.071 |

| Log median household income | 10.69 | 0.50 | 10.48 | 0.49 | 10.41 | 0.52 | 10.54 | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| % below FPL | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| % receiving public assistance | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| % unemployed | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| % under 18 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.25 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| % male 15 to 24 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.002 |

| % Black | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.56 | 0.43 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| % Hispanic | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.042 |

| % vacant units | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.055 |

| % own home | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.42 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.001 |

| # of TIF projects | 0.12 | 0.65 | 0.21 | 0.72 | 0.26 | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.74 | 0.047 |

| # of affordable mental health facilities | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | <0.001 |

| # of FQHCs | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.080 |

| Number of block groups | 2147 | 182 | 95 | 87 | |||||

- Note: Table displays 2008–2011 unweighted averages. p Values from two-sided t-tests for differences in means comparing block groups within a half mile of closed MHCs to block groups within a half mile of those that remained open.

If residents experiencing more economic hardship made greater use of the clinics, the baseline characteristics presented in this table partly corroborate claims made by CDPH that the shuttered MHCs were underutilized compared to clinics that remained open. Yet it is worth noting that there were no affordable mental health facilities in block groups within a half mile of closed MHCs in the preclosure period. The absence of alternative providers in these areas supports claims by critics that the clinics filled a critical need that went unmet after the closures.

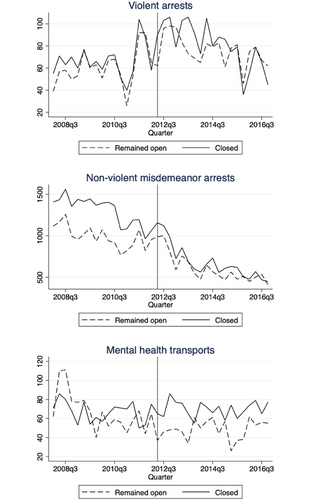

We motivate our analysis with plots illustrating arrest and mental health transport trends over our study period. As seen in the top panel of Figure 2, arrests for violent crimes in block groups within a half mile of MHCs that closed resembled those in block groups near MHCs that remained open for much of the preclosure period. After the closures, violent arrests near the closed MHCs exceeded those near open MHCs for roughly two years. Turning to the middle panel, we see that before the closures, arrests for nonviolent misdemeanors were noticeably higher near the shuttered MHCs than those that remained open. However, these gaps began to narrow roughly two quarters before the closures and tracked one another thereafter. In the third panel, it's evident that mental health transports fluctuated in the preclosure period, with block groups near the open MHCs experiencing more transports in the early period, lower levels after that, and levels similar to block groups near closed MHCs just before the closures. However, immediately after the closures, mental health transports increased in block groups near the shuttered MHCs and remained above those in comparison block groups for the remainder of the study period. In what follows, we assess if this descriptive evidence prevails once we take important confounding factors into account.

Quarterly trends in arrests and mental health transports by closure status. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Sample restricted to block groups with a half mile of MHCs. Vertical line indicates the quarter of MHC closure.

6.2 Main results

Table 2 reports difference-in-differences estimates predicting the relationship between the MHC closures and violent arrests, nonviolent misdemeanor arrests, and mental health transports. We first estimate a baseline specification that adjusts for quarter and block group fixed effects and subsequently control for time-varying block group sociodemographic characteristics, body-worn cameras, TIF projects, as well as affordable mental health facilities and FQHCs.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violent arrests | Nonviolent misdemeanor arrests | Mental health transports | ||||

| Baseline | Full | Baseline | Full | Baseline | Full | |

| MHC closure | ‒0.039 | 0.001 | ‒0.156* | ‒0.157* | 0.439*** | 0.411*** |

| (0.101) | (0.100) | (0.069) | (0.065) | (0.106) | (0.087) | |

| Observations | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.236 | 0.239 | 0.622 | 0.624 | 0.199 | 0.202 |

| Dep var mean | 0.824 | 0.824 | 10.638 | 10.638 | 0.789 | 0.789 |

| Quarter fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Block fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying cntrls | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from Poisson models predicting quarterly block group-level outcomes. The baseline models include quarter and block group fixed effects and estimates from the full model specification further adjust for time-varying block group characteristics outlined in Equation (1). Coefficient estimates for time-varying controls are reported in Table A2.

The coefficients reported in Table 2 reflect the change in each outcome following the closures in block groups within a half mile of MHCs that closed relative to block groups within a half mile of MHCs that remained open. As seen therein, regardless of the specification used, the closures did not have a statistically discernable impact on violent arrests but were associated with declines in nonviolent misdemeanor arrests and increases in mental health transports. Based on estimates from our full model specification, the closures were associated with a 15% drop in nonviolent misdemeanor arrests and a 51% increase in mental health transports.11

6.3 Robustness checks

In Table 3, we conduct a series of robustness checks to assess the sensitivity of our results to alternative model specifications. In column (1) of Table 3, we introduce a linear district time trend that allows arrests and mental health transports in different CPD districts to follow dissimilar patterns over time. This adjustment provides an additional control for changes in CPD programming that could influence police contact. Our findings are robust to this modification as violent arrests remain unchanged, while declines in nonviolent misdemeanor arrests and increases in mental health transports persist.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| District trend | Crime trend | OLS | Unweighted | |

| Panel A: Violent arrests | ||||

| MHC closure | 0.139 | 0.008 | 0.034 | 0.002 |

| (0.114) | (0.104) | (0.087) | (0.090) | |

| Observations | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 |

| Pseudo R2† | 0.241 | 0.239 | 0.349 | 0.241 |

| Dep var mean | 0.824 | 0.824 | 0.824 | 0.783 |

| Panel B: Nonviolent misdemeanor arrests | ||||

| MHC closure | ‒0.180** | ‒0.156* | ‒3.224* | ‒0.167** |

| (0.059) | (0.066) | (1.436) | (0.059) | |

| Observations | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 |

| Pseudo R2† | 0.627 | 0.624 | 0.732 | 0.599 |

| Dep var mean | 10.638 | 10.638 | 10.638 | 9.677 |

| Panel C: Mental health transports | ||||

| MHC closure | 0.332*** | 0.422*** | 0.329*** | 0.374*** |

| (0.083) | (0.086) | (0.088) | (0.086) | |

| Observations | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 |

| Pseudo R2† | 0.206 | 0.202 | 0.359 | 0.182 |

| Dep var mean | 0.789 | 0.789 | 0.789 | 0.691 |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from Poisson models predicting violent arrests (Panel A), nonviolent misdemeanor arrests (Panel B), and mental health transports (Panel C), adjusting for quarter and block group fixed effects and time-varying block group controls. Column (1) includes CPD district time trends to account for district-specific changes over the study period, column (2) controls for block-group crime trends, column (3) reports estimates using OLS, and column (4) reports unweighted regression results.

- † Column (3) value reflects R2 from OLS regression.

Recognizing that changes in police contact may reflect shifts in criminal activity, in column (2) of Table 3, we introduce a crime trend variable that interacts block group-level index crime in 2007, the year before our study period, with a linear quarterly time trend.12 The inclusion of this control variable did not alter our results. As before, we see that the closures had no discernable impact on violent arrests but continue to be associated with decreases in nonviolent misdemeanor arrests and increases in mental health transports.

We then estimate our full model specifications using OLS to alleviate concerns that our results are driven by our choice of functional form. As seen in column (3) of Table 3, we continue to find that the closures reduced nonviolent misdemeanor arrests and increased mental health transports. While the magnitude of our estimates for nonviolent misdemeanor arrests increased under the OLS specification, likely due to the function's sensitivity to outliers, the direction of effect aligns with our main results.

In column (4) of Table 3, we remove population weights to assess whether our results are sensitive to their use. We continue to find that the closures reduced nonviolent misdemeanor arrests and increased mental health transports. The similarity of these estimates to those derived from our preferred model specification suggests that our results are not driven by more populous block groups, where the potential for police contact may be greater.

In Tables 4 and 5, we experiment with excluding block groups proximate to each MHC to ensure that our results are not reflective of idiosyncratic shifts near specific clinics. In Table 4, we drop block groups within a half mile of each closed MHC. We can see in Panel A that our null findings for violent arrests hold across each sample. In Panels B and C, reductions in nonviolent misdemeanor arrests and increases in mental health transports remain robust regardless of which MHC we drop from the sample. In Table 5, we exclude block groups located within a half mile of each MHC that remained open. In Panel A, we continue to see no association between the closures and violent arrests, and in Panel C, the increases in mental health transports we identified earlier persist. However, column (1) of Panel B reveals that reductions in nonviolent misdemeanor arrests are rendered statistically insignificant when block groups within a half mile of the Englewood MHC are dropped. This clinic would have served as the nearest open MHC for residents closest to half of the shuttered MHCs (Table A4). If the closures redirected patients to the Englewood MHC, as reported by some news outlets (Lydersen, 2015), this may have increased arrests near this clinic relative to those that closed.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHC dropped | Auburn-Gresham | Back of the Yards | Beverly-Morgan | Northtown Rogers Park | Northwest | Woodlawn |

| Panel A: Violent arrests | ||||||

| MHC closure | 0.012 | ‒0.013 | ‒0.005 | 0.071 | ‒0.000 | ‒0.012 |

| (0.108) | (0.105) | (0.101) | (0.102) | (0.103) | (0.103) | |

| Observations | 5724 | 6228 | 6228 | 6084 | 5652 | 5976 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.256 | 0.245 | 0.234 | 0.235 | 0.230 | 0.243 |

| Dep var mean | 0.792 | 0.807 | 0.831 | 0.797 | 0.908 | 0.803 |

| Panel B: Nonviolent misdemeanor arrests | ||||||

| MHC closure | ‒0.148* | ‒0.171* | ‒0.152* | ‒0.124* | ‒0.158* | ‒0.160* |

| (0.063) | (0.069) | (0.066) | (0.060) | (0.068) | (0.068) | |

| Observations | 5724 | 6228 | 6228 | 6084 | 5652 | 5976 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.641 | 0.622 | 0.622 | 0.576 | 0.616 | 0.632 |

| Dep var mean | 10.195 | 10.184 | 10.838 | 9.749 | 11.726 | 10.577 |

| Panel C: MH transports | ||||||

| MHC closure | 0.427*** | 0.420*** | 0.451*** | 0.272*** | 0.437*** | 0.418*** |

| (0.092) | (0.092) | (0.085) | (0.080) | (0.089) | (0.094) | |

| Observations | 5724 | 6228 | 6228 | 6084 | 5652 | 5976 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.214 | 0.209 | 0.202 | 0.160 | 0.192 | 0.211 |

| Dep var mean | 0.793 | 0.781 | 0.794 | 0.671 | 0.873 | 0.780 |

| For all specifications above | ||||||

| Quarter fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Block group fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from Poisson models predicting violent arrests (Panel A), nonviolent misdemeanor arrests (Panel B), and mental health transports (Panel C) using the full model specification outlined in Equation (1). Each column reports estimates for samples that iteratively exclude block groups within half a mile of each MHC that closed.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHC dropped | Englewood | Greater Grand | Greater Lawn | Lawndale | North River | Roseland |

| Panel A: Violent arrests | ||||||

| MHC closure | 0.048 | ‒0.001 | 0.025 | ‒0.006 | 0.004 | ‒0.062 |

| (0.111) | (0.105) | (0.102) | (0.108) | (0.101) | (0.108) | |

| Observations | 5976 | 5832 | 5940 | 6084 | 6372 | 5976 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.242 | 0.243 | 0.229 | 0.237 | 0.234 | 0.244 |

| Dep var mean | 0.784 | 0.867 | 0.883 | 0.801 | 0.847 | 0.777 |

| Panel B: Nonviolent misdemeanor arrests | ||||||

| MHC closure | ‒0.074 | ‒0.238*** | ‒0.158* | ‒0.150* | ‒0.155* | ‒0.162* |

| (0.060) | (0.062) | (0.068) | (0.070) | (0.066) | (0.081) | |

| Observations | 5976 | 5832 | 5940 | 6084 | 6372 | 5976 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.633 | 0.631 | 0.619 | 0.632 | 0.623 | 0.630 |

| Dep var mean | 10.327 | 10.930 | 11.341 | 10.775 | 10.872 | 10.190 |

| Panel C: MH transports | ||||||

| MHC closure | 0.380*** | 0.398*** | 0.420*** | 0.416*** | 0.405*** | 0.420*** |

| (0.090) | (0.093) | (0.091) | (0.090) | (0.088) | (0.097) | |

| Observations | 5976 | 5832 | 5940 | 6084 | 6372 | 5976 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.209 | 0.208 | 0.198 | 0.206 | 0.204 | 0.204 |

| Dep var mean | 0.784 | 0.814 | 0.835 | 0.806 | 0.801 | 0.744 |

| For all specifications above | ||||||

| Quarter fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Block group fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from Poisson models predicting violent arrests (Panel A), nonviolent misdemeanor arrests (Panel B), and mental health transports (Panel C) using the full model specification outlined in Equation (1). Each column reports estimates for samples that iteratively exclude block groups within half a mile of each MHC that remained open.

To better understand whether our findings are sensitive to the comparison used, in Table 6, we compare block groups located within a half mile of closed MHCs to block groups between 1 and 1.5 miles of the same clinics. These areas should be similar ecologically and sociodemographically to block groups proximate to the shuttered MHCs but far enough away to be less influenced by their closing.13 If our results are sensitive to this change, it could suggest that our findings are driven more by shifts around the MHCs that remained open rather than changes near the shuttered MHCs. As seen in column (1) of Panel B, when we make this change, the closures are no longer associated with declines in nonviolent misdemeanor arrests. Yet, while our estimates attenuate slightly, we continue to find that mental health transports increased following the closures. As seen in column (2), these results remain when we apply propensity score weights to account for preclosure covariate differences.14

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Full model specification | Propensity score weighted | |

| Panel A: Violent arrests | ||

| MHC closure | ‒0.081 | ‒0.031 |

| (0.084) | (0.085) | |

| Observations | 15,480 | 15,480 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.209 | 0.249 |

| Dependent variable mean | 0.601 | 0.687 |

| Panel B: Nonviolent misdemeanor arrests | ||

| MHC closure | ‒0.074 | ‒0.026 |

| (0.055) | (0.057) | |

| Observations | 15,480 | 15,480 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.581 | 0.620 |

| Dependent variable mean | 8.361 | 9.423 |

| Panel C: MH transports | ||

| MHC closure | 0.216* | 0.183* |

| (0.089) | (0.075) | |

| Observations | 15,480 | 15,480 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.164 | 0.172 |

| Dependent variable mean | 0.648 | 0.662 |

| For all specifications above | ||

| Quarter fixed effects | Y | Y |

| Block group fixed effects | Y | Y |

| Time-varying controls | Y | Y |

| Propensity score weights | N | Y |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from Poisson models predicting violent arrests (Panel A), nonviolent misdemeanor arrests (Panel B), and mental health transports (Panel C). Block groups within a half mile of the MHCs that closed are compared to block groups between 1 and 1.5 miles of the shuttered MHCs. Column (1) employs the full model specification outlined in Equation (1) weighted by block group population in 2008. Column (2) swaps population weights for propensity score weights that balance preclosure covariates across groups.

Collectively, these robustness checks corroborate our finding that the closures increased mental health transports. However, while our initial estimates suggested that the closures decreased nonviolent misdemeanor arrests in areas near the shuttered clinics, these results were highly sensitive to the use of block groups near open MHCs as a comparison. Because of this, we cannot confidently conclude that the closures affected patterns of arrest.

6.4 Identification check

An important consideration when interpreting the results presented above is the nonrandom nature of the MHC closures. While the specific rationale for closing the targeted MHCs was not clearly stated, if the closures were influenced by unobserved or unaccounted-for factors, such as the utilization of mental health services—as suggested by city officials (Quinn, 2018)—this would bias our results.

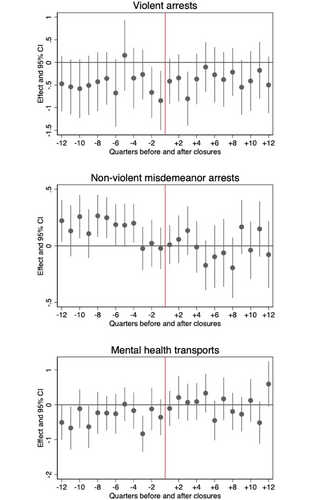

To address these concerns, we conducted event studies to gauge whether preclosure trends systematically differed in block groups within a half mile of shuttered MHCs relative to block groups near MHCs that remained open. Figure 3 displays the coefficients from Equation (2) predicting each outcome. Focusing on the top panel, we see that violent arrests in block groups located within a half mile of MHCs that closed were lower or statistically similar to those in block groups near MHCs that remained open for the entire study period. In the middle panel, we see that arrests for nonviolent misdemeanors near the shuttered MHCs exceeded those near MHCs that remained open for much of the preclosure period but began to equalize shortly before the closures, continuing a downward trajectory thereafter. The bottom panel reveals that mental health transports near the closed MHCs in the preclosure period were statistically similar or lower than those near MHCs that remained open.15 Yet after the closures, mental health transports began to increase. While these increases did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance, point estimates were positive in over half of the postclosure period but consistently negative in the preclosure period.

Event studies predicting the effect of MHC closures. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Note: Figures plot the coefficients from Equation (2) estimating the effect of the MHC closures on violent arrests, nonviolent misdemeanor arrests, and mental health transports. The reference period, , represents the quarter the MHCs closed and is marked by a red vertical line. Solid vertical bands around point estimates represent 95% confidence intervals for each coefficient.

Overall, the patterns in Figure 3 reveal that declines in nonviolent misdemeanor arrests started before the closures occurred, while increases in mental health transports did not emerge until after the closures. This gives us confidence that increases in mental health transports following the closures were not likely driven by unobserved or otherwise unaccounted-for factors.

6.5 Exploring mechanisms

The evidence provided up to this point suggests that the closures increased police contact in the form of mental health transports but not arrests. In what follows, we perform a series of supplemental analyses to better understand these shifts.

We begin by investigating whether the effect of the closures was more pronounced in areas closest to the shuttered MHCs. Table 7 includes estimates from our full model specification for three subsamples: block groups located within a quarter mile, between a quarter and a half mile, and those between a half and one mile of MHCs. In Panel A, we continue to see that the closures had no discernable impact on arrests for violent crimes. In Panel B, we see that reductions in nonviolent misdemeanor arrests were only observed in block groups between a quarter and a half mile of MHCs. While this seems counterintuitive, as we would expect changes to manifest closer to the closure sites, we remind readers that these declines are strongly influenced by the comparison used and are likely not indicative of shifts in arrest-generating behavior near the closed clinics. In Panel C, mental health transports increased by 54% in the immediate vicinity of the closed MHCs and 44% in block groups between a quarter and a half mile of the clinics.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance from MHC | < 0.25 mi | 0.25−0.5 mi | 0.5−1.0 mi |

| Panel A: Violent arrests | |||

| MHC closure | ‒0.073 | 0.042 | 0.115 |

| (0.149) | (0.139) | (0.078) | |

| Observations | 2808 | 3744 | 11,664 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.225 | 0.260 | 0.276 |

| Dependent variable mean | 0.871 | 0.789 | 0.796 |

| Panel B: Nonviolent misdemeanor arrests | |||

| MHC closure | ‒0.114 | ‒0.182* | ‒0.091 |

| (0.099) | (0.077) | (0.071) | |

| Observations | 2808 | 3744 | 11,664 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.613 | 0.635 | 0.634 |

| Dependent variable mean | 11.208 | 10.206 | 10.388 |

| Panel C: Mental health transports | |||

| MHC closure | 0.435** | 0.364*** | 0.107 |

| (0.134) | (0.100) | (0.074) | |

| Observations | 2808 | 3744 | 11,664 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.198 | 0.207 | 0.162 |

| Dependent variable mean | 0.901 | 0.705 | 0.658 |

| For all specifications above | |||

| Quarter fixed effects | Y | Y | Y |

| Block group fixed effects | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying controls | Y | Y | Y |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from Poisson models predicting violent arrests (Panel A), nonviolent misdemeanor arrests (Panel B), and mental health transports (Panel C) using the full model specification outlined in Equation (1). Each column reports estimates for a different sample of block groups based on their geographic proximity to MHCs. Column (1) restricts the sample to block groups within a quarter mile, column (2) between a quarter and a half mile, and column (3) between a half and a full mile of MHCs.

Next, we consider whether the closures affected requests for police presence, as it may be the case that residents near the MHCs became more vigilant after the closures and called the police more often. To explore whether our results reflect residents activating the criminal justice system, in Table 8, we estimate whether 911 calls changed in areas within a half mile of the shuttered MHCs relative to those that remained open. We find no evidence that the closures affected total calls nor calls related to mental health disturbances. These results suggest that increases in mental health transports were not simply reactive responses by police but may have stemmed from proactive police activity following the closures.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total CFS | MH-related CFS | |

| MHC closure | 0.020 | 0.102 |

| (0.036) | (0.080) | |

| Observations | 6552 | 6552 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.834 | 0.298 |

| Dep var mean | 198.458 | 2.064 |

| For all specifications above | ||

| Quarter fixed effects | Y | Y |

| Block group fixed effects | Y | Y |

| Time-varying controls | Y | Y |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from Poisson models predicting the total number of calls and mental health-related calls for police service using the full model specification outlined in Equation (1). We arrive at similar results using OLS.

Lastly, we explore whether the closures affected transit patterns as resident activity near the MHCs may have changed in the wake of the closures. In the absence of clinical care, this could have influenced the social control responsibilities of the police or impacted the probability of socially deviant behavior and risk of victimization. To assess this, we examine CTA ridership patterns. While not a perfect representation of resident activity, CTA ridership should indicate whether the closures diverted traffic away from the closed MHCs. Yet, as seen in columns (1) and (2) of Table 9, the total number of passengers riding CTA buses and “L” trains that pass through block groups within a half mile of the shuttered MHCs did not change following the closures compared to ridership around the MHCs that remained open. While we cannot definitively say that those served by the shuttered clinics were not diverted to alternative locations, this finding suggests that the closed clinics continued to be sites of routine activity, which aligns with our main findings.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| CTA bus rides | CTA “L” rides | |

| MHC closure | ‒83.943 | 161.793 |

| (52.155) | (144.776) | |

| Observations | 6552 | 6552 |

| R2 | 0.985 | 0.882 |

| Dep var mean | 9778 | 3423 |

| For all specifications above | ||

| Quarter fixed effects | Y | Y |

| Block group fixed effects | Y | Y |

| Time-varying controls | Y | Y |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from OLS models predicting the number of Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) bus and “L” rides adjusting for quarter and block group fixed effects and time-varying block group-level controls. Estimates are weighted using block group populations in 2008. Standard errors are in parentheses and clustered at the block group level.

7 DISCUSSION

Critics continue to argue that the 2012 closure of half of Chicago's public mental health clinics created service shortages that diverted untreated patients to the criminal justice system. We explored these claims by examining whether and to what extent the closures affected patterns of criminal justice contact in areas proximate to the shuttered clinics. Using block group-level data on arrests and mental health transports made by CPD officers between 2008 and 2016, we compared trends in areas within walking distance of the closed clinics to those equidistant from clinics that remained open. We found that the closures increased police-initiated mental health transports near the shuttered clinics. These results were robust to the inclusion of various sociodemographic and ecological controls, the rollout of body-worn cameras, local development projects, and the presence of alternative low-cost mental and physical health care facilities, as well as alternative model specifications and samples. Further, event studies suggest that our results were not likely driven by unobserved or otherwise unaccounted-for factors.

We did not find robust evidence that the closures increased arrests. While our initial estimates suggested that the closures decreased nonviolent misdemeanor arrests, these results were highly sensitive to our use of block groups near open MHCs as a comparison. More specifically, they were driven by block groups within walking distance of the Englewood MHC—the nearest open MHC for residents closest to half of the shuttered clinics. While this could indicate that the closures redirected individuals with untreated mental health conditions to the nearest open MHC, leading to increased police contact for minor offenses, we remain cautious about drawing overly broad conclusions from this finding due to its reliance on a single clinic.

Our findings regarding arrests diverge from previous research that has linked improved mental health care access with reductions in arrest. However, our study presents a unique perspective by examining the localized effects of clinic closures rather than broader geographic trends and the impact of increased access to mental health services. This localized approach allows us to capture shifts that might be obscured in studies using aggregated data from multiple law enforcement agencies with diverse mental health policies. While the closures did not lead to increased arrests, they did result in more police-initiated mental health transports, highlighting a shift in the role of police within the broader health care system. This suggests that the social control of mental illness is evolving, with police increasingly facilitating access to emergency mental health care rather than funneling individuals into the criminal justice system. Our results challenge the common assumption about the direct relationship between jails and mental health services, indicating that reduced mental health care access does not necessarily lead to more arrests. Instead, it may prompt a reallocation of responsibilities, with police stepping in to manage acute mental health crises. This shift underscores the need to rethink how we address mental health within the framework of public safety and social control.

Although we could not conclusively pinpoint the exact factors that caused an uptick in mental health transports, we were able to rule out some explanations. We did not find evidence that the closures affected requests for police presence or foot traffic near the shuttered clinics. Instead, the closures likely created an opportunity for police to proactively initiate contact. This response in the immediate vicinity of the closed MHCs suggests that the clinics served a localized group of patients who may not have resorted to alternative transportation to access other sites. These findings raise important questions about who is served by MHCs and how barriers to care further expose poor and marginalized communities to law enforcement.

Taken together, our findings suggest that the closures shifted social control responsibilities from geographically based mental health care facilities to the criminal justice system. While the closures did not influence the arrest-generating behavior of individuals near the closed clinics, they placed police officers in the position of managing the distribution of patients throughout the city through mental health transports. In this capacity, officers played a “connecting” role to the emergency medical system, which accords with prior research showing that hospitalization is a preferred response among CPD officers responding to mental health calls (Watson & Wood, 2017). This response could demonstrate a form of “burden shuffling” (Seim, 2017), where officers transfer the responsibility of managing untreated mental health conditions—or poverty, more broadly—from the criminal justice system to the medical system. Ultimately, our findings indicate that the closures increased police contact and, subsequently, transportation to less specialized emergency care facilities, which likely had minimal impact on long-term mental health outcomes (McKenna et al., 2015). These shifts in the social control landscape could have dire consequences for affected communities given the amplified risk of fatal police encounters for individuals exhibiting signs of mental health issues (Saleh et al., 2018). Using the criminal justice system to meet health care needs blurs the relationship between these two institutions in ways that undermine personal agency and increase dependence on law enforcement for basic needs.

While this study is the first to examine the criminal justice implications of Chicago's 2012 clinic closures, it is not without limitations. Though we know that the city's public mental health clinics provided care for people with serious mental health disorders, we lack detailed information on the quantity or quality of treatment. This limits our ability to discern the specific services that, when removed, increased the conditions for police contact. Additionally, we lack information on the quality of services provided by the clinics, which prevented us from investigating whether the type or standard of care precluded criminal justice contact. Further, we focus our attention on arrests and mental health transports—two common police responses when encountering individuals experiencing mental health episodes. We did not examine situations where police resolve situations informally, such as calming down individuals or moving persons to different locations (Watson & Wood, 2017; Wood et al., 2017). As a result, our study may understate the full extent of police contact following the closures. Lastly, our results speak to the period before and after the closures, which predates recent reforms and investments in affordable mental health services in the city. Shifting CPD policies concerning mental health encounters and programs like Crisis Assistance Response and Engagement teams—where an officer, mental health clinician, and paramedic are jointly dispatched to mental health-related calls—may amplify the prioritization of emergency care over arrest. Future research might consider how these efforts shape patterns of criminal justice contact and patient outcomes.

Debates surrounding the criminal justice consequences of Chicago's controversial clinic closures are center-of-mind today as the city waits to see if Mayor Brandon Johnson will follow through on his campaign promise to reopen the shuttered clinics (Woelfel, 2023). This comes on the heels of Mayor Lori Lightfoot's term as mayor, who reneged on a similar campaign promise (Nelson, 2021; Spielman, 2020), deciding instead to bolster short-term investments in community-based mental health care (Mayor's Press Office, 2021). Advocates argue that public mental health clinics are an important safety net that ensures the city's most vulnerable residents have access to mental health care (Nelson, 2021). The fact that neighborhoods experiencing the most severe shortages in mental health care are also disproportionately exposed to law enforcement only bolsters arguments that public clinics are an important refuge from criminal justice contact.

This study sheds important light on the consequences of reduced access to mental health services that policymakers should consider when deliberating paths forward. Our findings emphasize the importance of mental health care access and punctuate the need for adequately funded and functional mental health services in systemically disinvested neighborhoods. While efforts to train officers in crisis intervention and deploy clinicians and emergency responders to mental health incidents are well-warranted, they treat the symptoms of what is fundamentally a public health issue and do little to address the shortage of accessible, affordable, and consistent behavioral health treatment in the city. Policy efforts should focus on bolstering mental health services and crisis prevention resources that preclude police from acting as mental health responders of last resort.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was ably supported by PhD candidate Michael Disher and undergraduate research assistants Victoria Thor, Lisa King, and Hanee Chang. We are grateful to Emily Owens, Julie Wiegandt, Solveig Cunningham, and participants at the University of North Texas Colloquium for helpful feedback on working versions of this paper. We also thank Patrick Burke and Patrick Corrigan for their insights on mental health care and police response in Chicago.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This project benefited from a Creative Activity Award granted by the University of Illinois Chicago Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and a Rapid Response Grant from the Institute for Research on Race and Public Policy at the University of Illinois Chicago.

ENDNOTES

- 1 We use quarterly counts as they are small enough to detect changes over time but large enough to avoid low outcome counts per block group.

- 2 While we recognize that violent crimes are rare events, we include them in our analysis to better understand how the closures may have affected arrest-generating behavior.

- 3 Individuals are typically transported via ambulance. Once an ambulance arrives, they are assessed by paramedics and taken to the nearest intake facility with the responding officer riding along or following the ambulance. On rare occasions, an individual may be restrained and transported by a CPD squadrol. It is also possible for an individual to be transported by an officer, though this is also uncommon.

- 4 Though the Cook County Health and Hospital System took over management of the Roseland MHC in the final months of 2016, we kept block groups near this MHC in our set of comparison sites. Results are robust to their exclusion.

- 5 While walking distance is usually considered within 0.25 miles, studies have found that the median distance people walk is 0.5 miles per trip (Yang & Diez-Roux, 2012).

- 6 We downloaded this list on December 20, 2022 from findtreatment.gov.

- 7 Directories for 2009 to 2011 were unavailable. If a facility was present in the 2008 and 2012 directory, we assumed they were operational in 2009, 2010, and 2011. If a facility was in the 2008 directory but not in the 2012 directory, we assumed they were operating in 2009 and 2010, but not 2011.

- 8 “Look-alikes” meet the eligibility requirements of an FQHC but do not receive Health Center Program funding.

- 9 All six MHCs closed in April 2012.

- 10 We used Poisson over a negative binomial fixed effects model as it is robust to different variance-mean relationships and allows for serial correlation (Guimarães, 2008; Wooldridge, 1999). We estimated these models using the ppmlhdfe command in Stata (Correia et al., 2020).

- 11 Computed as: (. Coefficient estimates for time-varying controls are reported in Appendix Table A2. Declines in non-violent misdemeanor arrests stemmed from drops in simple assault arrests (Appendix Table A3).

- 12 Data were retrieved from: https://data.cityofchicago.org/Public-Safety/Crimes-2001-to-Present/ijzp-q8t2. Index crimes include homicide, rape, robbery, burglary, aggravated assault, larceny over $50, motor vehicle theft, and arson. We do not directly control for incidents because crime and police contact mutually influence each other.

- 13 We dropped 51 block groups within 1.5 miles of MHCs that remained open to ensure that changes in these areas did not affect our results.

- 14 We derived propensity score weights that balance covariates in the first quarter of 2011 between block groups within a half mile of closed MHCs to block groups between 1 and 1.5 miles of these clinics. Weights were calculated using Stata's psmatch2 command employing a 0.3 caliper as the maximum acceptable difference in propensity scores between matched units.

- 15 While not all coefficients were equal to zero during the preclosure period, we do not see evidence of a clear upward or downward trend. This gives us confidence that the increases detected in our difference-in-differences models are not an extension of pre-closure trends.

APPENDIX

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General services | Emergency services | ||||||

| MHC | PTSD | CJ referral | SED (youth) | SMI (adult) | Co-occurring MH & SA | Psych walk-in | CIT |

| Closed | |||||||

| Auburn-Gresham | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Back of the Yards | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Beverly/Morgan Park | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Northtown Rogers Park | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Northwest | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Woodlawn | x | x | |||||

| Remained open | |||||||

| Englewood | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Greater Grand | x | x | |||||

| Greater Lawn | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Lawndale | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| North River | x | x | x | ||||

| Roseland | x | ||||||

- Note: Table lists select services provided in each MHC using information in the 2012 SAMHSA Directory of US Mental Health Facilities. We requested related details for Lawndale, Northtown Rogers Park, and Northwest MHCs from CDPH because these clinics were not included in the SAMHSA directory. Each column indicates whether the respective MHC offered special programs or services for persons: (1) experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder, (2) referred to the MHC by the criminal justice system, (3) under age 18 experiencing severe emotional disturbance, (4) age 18 and over with serious mental illness (i.e., bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, schizophrenia), and (5) with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders. Columns (6) and (7) indicate whether the MHC provided walk-in services for individuals experiencing psychiatric emergencies or had professionals trained in crisis intervention at the facility, respectively.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Violent arrests | Nonviolent misdemeanor arrests | Mental health transports | |

| MHC closure | 0.001 | ‒0.157* | 0.411*** |

| (0.100) | (0.065) | (0.087) | |

| Log population | 0.099 | ‒0.024 | ‒0.008 |

| (0.148) | (0.160) | (0.162) | |

| Log median hhld inc | 0.094 | 0.093 | ‒0.120 |

| (0.138) | (0.075) | (0.114) | |

| Percent below FPL | 0.353 | 0.023 | ‒0.163 |

| (0.322) | (0.177) | (0.371) | |

| Percent public assist | 0.595 | 0.630 | 1.604* |

| (0.580) | (0.419) | (0.632) | |

| Percent unemployed | ‒0.076 | ‒0.026 | 0.491 |

| (0.307) | (0.257) | (0.347) | |

| Percent under 18 | ‒1.026* | ‒0.439 | 0.222 |

| (0.402) | (0.344) | (0.453) | |

| Percent male 15 to 24 | ‒0.060 | 0.138 | 0.989 |

| (0.672) | (0.571) | (0.708) | |

| Percent Black | 1.025 | 1.001* | 0.770 |

| (0.735) | (0.446) | (0.620) | |

| Percent Hispanic | 1.392** | 0.584 | 0.249 |

| (0.516) | (0.374) | (0.500) | |

| Percent vacant units | 0.210 | 0.163 | ‒0.959** |

| (0.365) | (0.323) | (0.371) | |

| Percent own home | ‒0.248 | ‒0.276 | ‒0.220 |

| (0.264) | (0.213) | (0.315) | |

| BWCs | ‒0.630** | 0.072 | ‒0.001 |

| (0.214) | (0.098) | (0.197) | |

| TIFs | 0.215* | 0.052 | 0.115 |

| (0.089) | (0.030) | (0.079) | |

| MH providers | 0.154 | 0.285** | 0.053 |

| (0.289) | (0.096) | (0.187) | |

| FQHCs | 0.070 | 0.000 | ‒0.069 |

| (0.186) | (0.087) | (0.229) | |

| Observations | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.239 | 0.624 | 0.202 |

| Dep var mean | 0.824 | 10.638 | 0.789 |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from Poisson models using the full model specification outlined in Equation (1).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Violent arrests | Homicide | Sexual assault | Robbery | Agg assault | Agg battery |

| MHC closure | 0.320 | ‒0.014 | ‒0.054 | 0.040 | 0.014 |

| (0.298) | (0.478) | (0.150) | (0.134) | (0.212) | |

| Observations | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.192 | 0.325 | 0.214 | 0.209 | 0.221 |

| Dep var mean | 0.047 | 0.030 | 0.369 | 0.259 | 0.109 |

| Panel B: Nonviolent misdemeanor arrests | Simple battery | Drugs | Criminal trespassing | Larceny | Simple assault |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHC closure | ‒0.034 | ‒0.170 | ‒0.291 | ‒0.168 | ‒0.182* |

| (0.065) | (0.097) | (0.154) | (0.124) | (0.092) | |

| Observations | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 | 6552 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.323 | 0.608 | 0.385 | 0.568 | 0.223 |

| Dep var mean | 2.186 | 2.168 | 1.613 | 1.322 | 0.573 |

| For all specifications above | |||||

| Quarter fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Block group fixed effects | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Time-varying controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

- Note: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. Table displays estimates derived from Poisson models using the full model specification outlined in Equation (1). Panel A reports estimates predicting the impact of MHC closures on arrests for homicide, sexual assault, robbery, aggravated assault, and aggravated battery. Panel B reports the estimated effect of the closures on the five most common types of nonviolent misdemeanor arrests: simple battery, drug offenses, criminal trespassing, larceny, and simple assault.

| MHC preclosure | Avg preclosure commute time (minutes) | MHC postclosure | % of block groups | Avg postclosure commute time (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|