Tradition as a resource: Robust and radical interpretations of operatic tradition in the Italian opera industry, 1989–2011

Giulia Cancellieri, Gino Cattani, and Simone Ferriani contributed equally to this study.

Abstract

Research Summary

A major challenge that organizations face in cultural industries in dealing with cherished traditions is how to best mediate between adherence to tradition and pursuit of innovation, how to accommodate renewal without stifling tradition. We address this conundrum by integrating ideas from consumer-oriented psychological research on evaluative judgments and design-oriented innovation research. We show that firms can improve customers' perceptions of value by offering robust interpretations of traditional products that preserve the most familiar aspects of a tradition while departing from it on more peripheral features; however, when the interpretation is more radical—that is, it alters core elements of the tradition—customers are more likely to experience incongruity with their schemas, resulting in a negative perception of value. We also postulate that different audience segments will respond differently to the (re)interpreted tradition because individuals vary in the use of generic schemas depending on their level of expertise, and different schemas may accommodate smaller or greater changes in a configuration of attributes. We develop and test these hypotheses in the context of the Italian opera industry over the period 1989 to 2011. The results offer insights into how firms can maintain a sense of continuity with a revered tradition while ensuring its renewal over time.

Managerial Summary

Reinterpreting revered traditions is a way to exploit timeless resources encased in history by recasting them in new ways. This article reveals how firms can balance tradition and innovation through the design choices they make, thus expanding the range of strategic tools that can be leveraged to influence customers' perceptions of value. In doing so, it helps managers address the need for renewal, while at the same time remaining sensitive to the heterogeneity of different customer segments, by manipulating the core and/or peripheral features of a product (here the opera). Although firms in cultural industries often face the challenge of resolving the tension between the preservation of tradition and risky innovation, many other firms across different industries also confront the issue of developing new products while building intimate links with their traditions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Management and organizational scholars have paid increasing attention to the role of tradition in strategy making (Dacin et al., 2010; Dacin & Dacin, 2008; De Massis et al., 2016). One exciting trajectory of this literature focuses on how organizations use tradition as a resource and, in particular, how managers leverage tradition to preserve valued rituals, support desired identities, and bolster firm performance. Dacin et al. (2019), for instance, use the term custodians to refer to individuals or organizations that “maintain and adapt traditions because, far from constraining action, traditions enable them to accomplish important goals” (p. 351). Eyerman and Jamison (1998) similarly characterized tradition as a process of connecting a selected or usable past to contemporary life. It is through this process that traditions “are interpreted and reinterpreted by successive generations in an ever-moving present” (Suddaby & Jaskiewicz, 2020, p. 235). Likewise, Soares (1997) defined tradition as a resource linking the past to the future, more precisely a “cultural resource which patterns the responses of particular communities to contemporary challenges” (p. 14). Collectively, these views share an interest in how actors vested in the continuity of traditions proactively, and often strategically, link the past to the future through a “continuous work of interpretation” (Giddens, 1994, p. 64).

Yet the actual understanding of how this interpretation of the past occurs in contemporary strategy making is still limited. This is a significant shortcoming in light of consistent managerial evidence suggesting that traditions may be less malleable than typically assumed, as revered traditions may trap firms into their historical rituals, values, and symbols (De Massis et al., 2016; Sasaki et al., 2019). For instance, recent findings indicate that long-lived firms may be reluctant to abandon their traditions and rather seek opportunities to leverage a cherished past (Cattani, Dunbar, & Shapira, 2017; Erdogan et al., 2019). Sasaki et al.'s (2019, p. 815) findings in the context of long-lived Japanese firms similarly suggest that commitment to tradition may impose “constraints on the latitude that […] managers have when trying to change and innovate,” locking firms in the continuation of historical trajectories. These conflicting demands between preserving a sense of continuity and supporting change reflect two competing approaches to using tradition: conservative past and risky novelty (Foster et al., 2015). When they follow a conservative strategy and adhere to a tradition in their domain, organizations enjoy the benefits of a clear identity, unambiguous expectations, and well-honed routines but forgo opportunities to attract customers who instead value and appreciate innovation. When they follow a risk-taking strategy, however, organizations fail more frequently. On the other hand, if a risky project succeeds, it may have a profound impact, yielding recognition, and winning acclaim.1 This poses a challenge for strategists dealing with cherished traditions: How to best mediate between past origins and future developments? How to accommodate renewal without stifling tradition?

To address this conundrum, we build upon recent work that has considered the strategic choices that can be made to enhance the reception of new products (Cattani, Ferriani, & Lanza, 2017; Hargadon & Douglas, 2001; Kim & Jensen, 2011; Rindova & Petkova, 2007; Younkin & Kashkooli, 2020) and propose that one solution to this dilemma resides in the design choices firms make about the product form in which they embed their revered traditions. By integrating ideas from consumer-oriented psychological research on evaluative judgments (Mandler, 1982; Moreau et al., 2001; Stayman et al., 1992) and design-oriented innovation research (Hargadon & Douglas, 2001; Rindova & Petkova, 2007), we argue that firms can improve customers' perceptions of value through interpretations of traditional products that preserve the most familiar aspects of a tradition while departing from it on more peripheral features. This interpretation strategy allows organizations to reconcile the simultaneously enabling and constraining effects of a revered past by pursuing novelty that remains within the boundaries of tradition. However, when the interpretation is more radical, causing alterations to the tradition's core elements, customers are more likely to experience incongruity with their schemas resulting in a negative perception of value.2 We also postulate that different audience segments will respond differently to the (re)interpreted tradition because individuals vary in the use of generic schemas depending on their level of expertise (Moreau et al., 2001), and different schemas may accommodate smaller or greater changes in a configuration of attributes.

We develop and test these hypotheses in the context of the Italian opera industry over the period 1989–2011. Italian opera houses are nonprofit companies that have to address the inherent dilemma between honoring a venerable tradition of operatic classics and renewing it to meet audiences' expectations. Like other studies developing context-specific hypotheses, we conducted several interviews to gain a deeper understanding of our setting. In-depth discussions with several artistic directors emphasized the need to consider opera goers' past understanding and experience with traditional content while retaining the flexibility to renew it by transposing the core elements of tradition into new spatial and temporal contexts. However, the same directors also recognized the risk of a backlash when those alterations involve elements more strongly linked to tradition. Thus, we hypothesize that opera productions can improve market appeal by prioritizing interpretations of tradition that preserve core dramaturgical and musical attributes while altering peripheral visual elements. We call this strategic approach robust interpretation strategy. In contrast, manipulating core attributes of tradition is likely to reduce market appeal. We call this approach radical interpretation strategy. Finally, interviewees indicated that opera goers vary markedly in their degree of operatic connoisseurship and this heterogeneity, in turn, affects their response to different manipulations of the operatic tradition. Building on recent research on audience heterogeneity in orientation toward novelty (Cattani et al., 2014; Cattani, Ferriani, & Lanza, 2017; Jensen & Kim, 2014; Kim & Jensen, 2011; Pontikes, 2012), we further predict that the effectiveness of robust and radical interpretations varies with opera goers' level of expertise. Observational data lend credence to our arguments and enrich the emerging understanding of tradition as a resource that can be strategically interpreted to shape customers' perceptions of value.

2 LEVERAGING TRADITION THROUGH (RE)INTERPRETATION

Although management scholarship at the interface between tradition and strategy making is relatively young, its antecedents are not. Precursors of this literature can be found in sociology (Shils, 1975, 1981), followed by research on organizational culture (Barley et al., 1988), and continuing to this day with a greater appreciation for the distinctiveness of tradition as a construct in organizational research (Dacin et al., 2010; Dacin & Dacin, 2008; Dacin & Dacin, 2019; Di Domenico & Phillips, 2009). This focus on tradition in management and organizational scholarship is also part of a broader renewed interest in the use of history as a resource and—most crucial for our purposes—in how managers periodically revisit and re-construct history vis-à-vis current concerns and future plans (Rowlinson et al., 2014; Vaara & Lamberg, 2016).

A particularly interesting line of inquiry examines the challenges that firms competing in product market settings face as they seek to reconcile the simultaneously enabling and constraining effect of a revered past and, more generally, how they address the inherent tension between cocooning valued traditions and renewing them to carry them forward into the future. As organizational scholars have repeatedly pointed out (March, 1991), establishing continuity while changing is not easy, as attachment to past values and rituals that fuel traditions may also foster inertia and limit firms' ability to meet market needs (Maclean et al., 2014). According to Eyerman and Jamison (1998, p. 34), this tension reflects a paradox at the heart of tradition, which “both looks back, or remembers, a long-lost past, and transforms, or reconstructs […] that which is being remembered or imagined, as it is being realized.”

Nowhere is perhaps this paradox more tangible than in fields of cultural production where adherence to tradition yields the benefits of reassuring clarity and legitimacy, yet producers are keenly aware that long-term survival and reputation depend on novelty (Lampel et al., 2000). How can then tradition and innovation work productively together? As Jauss (1988, p. 376) eloquently put it, “tradition realizes itself neither in epic continuity nor in a creation perpetua, but in a process of mutual production and reception, determining and redetermining canons, selecting the old and integrating the new […] through selection, forgetting and reappropriation.” It is because of this constant mediation between past origins and future developments that cherished traditions can survive and imbue events, products, or practices with renewed meaning and value (Suddaby & Jaskiewicz, 2020). Yet our understanding of how this act of mediation occurs in contemporary strategy making is still limited. To address this limitation and shed light on how firms in competitive markets deal with the tradition/innovation tension, we borrow from research on the strategic choices that firms make to improve customers' perceptions of product value and propose a variety of approaches to (re)interpreting traditional material in a way that is consistent with customers' expectations and cognitive orientation.

3 EMPIRICAL CONTEXT AND HYPOTHESES

Our empirical setting is the Italian opera industry. Nowadays the operatic world is the epitome of a context that shows custodial responsibility to the past and the future (Soares, 1997). Indeed, as Levin (1994, p. 114) noted, opera houses are “associated to a tradition marked by the continuity of perennial values (‘It's as beautiful as ever, Aida’).” And with Italy being the birthplace of opera, Italian opera houses have been especially wary of preserving this revered art form by populating their programs with traditional pre-twentieth century operas such as Giuseppe Verdi's La Traviata or Giacomo Puccini's La Tosca, which have come to define operas for many audiences. On the other hand, as nonprofit art institutions exist partly to advance and renew operatic art, opera houses strongly aspire to innovation and artistic originality. This focus on novelty not only helps support their artistic legitimacy but also provides aesthetic material for growth and creative change in the operatic world. Previous research in the context of the US opera industry has shown that opera houses can address this challenge by changing the ordering (interspersion) between conventional (more frequently staged) and unconventional (less frequently staged) operas in their seasonal repertoires but “without making substantive changes to their products or product portfolios” (Kim & Jensen, 2011, p. 238). Instead, our fieldwork in the Italian opera scene has revealed that opera houses increasingly seek to navigate this balance by reinterpreting traditional works in novel ways (see also Snowman, 2010).3

We consulted archival sources and conducted interviews to gain insights into how opera houses conceptualize the simultaneously enabling and constraining effects of a revered past, and how they deal with the inherent dilemma between preservation and alteration whenever they conceive of novel ways of interpreting the tradition. Starting with a world-renowned artistic director of one of the most prominent opera houses in Italy, we then used a snowball approach to identify other informants: nine artistic directors and one managing director of medium and large size opera houses based in northern Italy, four artistic directors of small size opera houses and festivals in northern and central Italy and one invited stage director. Three of the artistic directors we interviewed also have experience as stage directors. Overall, we conducted 15 interviews that lasted from 20 min to 1 hr and a half. Table S1 in Appendix S1 summarizes the characteristics of our respondents, while Table S2 in Appendix S1 compiles the most representative quotes from our informants, organized around the central themes that animate this article. We complemented the fieldwork with a comprehensive reading of specialized books, scholarly articles, industry reports, and press articles from the opera sector's leading publications (Table S3 in Appendix S1).

“We have been recognized as a stronghold of tradition. This perception […] has a positive meaning because our theater has a long and glorious tradition (but) it limits our actions […] opera should be regenerated to be vital […] if we produce only the same type of opera, we renounce to the fundamental role that every creative project must have […] We are responsible of the future of opera and there is no future without artistic renewal” (Artistic Director Opera House # 5).

Of course, (re)interpreting a revered classic can result in broad acclaim or disastrous critique not merely due to the underlying organizational and aesthetic challenges inherent in mixing traditional elements with novel features, but because some of these combinations may signal a stronger or weaker departure from the tradition. For example, an interpretation of Madame Butterfly that dresses up the 100-year-old opera with contemporary scenography and costumes may receive less criticism than the same opera transposed into a contemporary setting in which the protagonist is dead from the beginning and is singing as a disembodied ghost haunting the stage, while black ninjas become threatening ancestors.4 In both cases, the director recasts the operatic tradition in novel ways, potentially increasing its value by breathing new life into it. However, the end products are unlikely to be treated as equally appealing by their customers. More than the technical barrier, this example underscores the perceptual challenge associated with appreciating a signal that at the same time prompts comparison to and departure from a schematic ideal, consistently with schema theory language (Mandler, 1980, 1982; Taylor & Crocker, 1981).“Traditional operas are not museum works […] with today's sensibility we have to make them live again” (Artistic Director Opera House # 2).

To theorize on when the interpretation of tradition elicits a favorable response, we first note that any act of reinterpretation causes a cognitive gap between the configuration of features that make up the reinterpreted object and the configuration of features specified by the generic schemas used for its processing (Meyers-Levy & Tybout, 1989). Schemas are abstract representations of environmental regularities that organize experience and develop through it. Psychological research on value judgments suggests that these general schemas set expectations that affect how audiences judge any given object of evaluation (Mandler, 1982; Moreau et al., 2001). It follows that the degree of incongruity caused by the reinterpretation of traditional work, which depends on whether the reinterpretation changes core or peripheral features of the tradition, will affect the reception of the resulting product by the target audience. Our hypotheses focus on how the degree of alteration affects the likelihood of the interpretation being positively received.

Marrying ideas from psychological research on value judgments with design-oriented innovation research (Hargadon & Douglas, 2001; Rindova & Petkova, 2007; Rothwell & Gardiner, 1984, 1988), we first suggest that opera houses can improve customers' perceptions of value by following what we term a robust interpretation strategy. In innovation and new product development research, a robust product design involves encasing novelty into the familiar through design, that is “the particular arrangement of concrete details that embodies an innovation” (Hargadon & Douglas, 2001, p. 478). Organizational sociologists typically use a notion of robustness inspired by Leifer's (1991) work to refer to an identity (Jensen & Kim, 2014; Zuckerman et al., 2003), a course of action (Padgett & Ansell, 1993; Sgourev, 2013) or a strategy (Ferraro et al., 2015) that is flexible as it allows actors to maintain engagement across conflicting positions and in the face of changing environmental conditions. Our use of this concept is more closely associated to design and new product development research (Luo et al., 2005; Rothwell, 1992; Rothwell & Gardiner, 1984, 1988; Swan et al., 2005).5 In describing how a new product is perceived by an observer, designers sometimes refer to a product's “visual robustness” to indicate its ability “to stimulate the same visual product experiences as the nominal design, despite small deviations in its visual design properties” (Forslund & Soderberg, 2010, p. 253). Our inspiration for the robust interpretation idea stems from this design-oriented line of work.

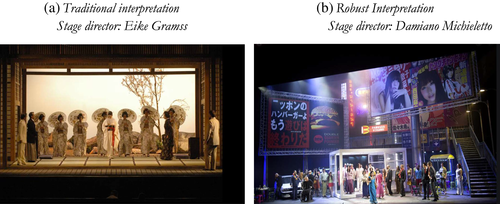

In the opera industry, a robust design strategy is deployed through interpretations that preserve the core aspects of a particular opera (i.e., its music and dramatic content) while departing from it on features that are more peripheral (i.e., its visual staging). The main intuition is that by working as an outer shell that amplifies the visual dissimilarity between the original material and the reinterpreted one, the staging allows opera houses to appeal to the sensibility of modern audiences. At the same time, the preservation of the music and dramatic content facilitates the cognitive change necessary to resolve the incongruity resulting from the new visual elements because opera goers can draw analogies (Gentner, 1983) from a familiar domain (the traditional opera) to a new target domain (the reinterpreted tradition).

This transposition process enhances customers' ability to extend or modify their schemas to accommodate discrepant information presented in the reinterpreted opera (Mandler, 1982). In the operatic context, it helps the audience interpret the visually innovative aspects of a traditional opera as moderately incongruous alterations that seek to refresh (rather than radically transform) the tradition, ultimately providing them with “the familiarity to understand what they are offered and the novelty to enjoy it” (Lampel et al., 2000, p. 264). Accordingly, we argue that increasing visual dissimilarity through robust interpretations can be an effective strategy as it moderately increases the incongruity of traditional operas. Operas appear then more interesting because altering their peripheral features results in new fresh experiences, but still allows opera goers to resolve the incongruity that these changes usually entail. Therefore, we suggest that opera houses can enhance the perceived value of their renewal efforts by pursuing a robust interpretation of tradition:“Director Damiano Michieletto has conceptually updated the story of Cio San […] The scene opens on the chaotic street of an evolved East Asian city: […] The story is modernized but the direction respects the music and follows the text (libretto) with precision and without excessive forcing, focusing on a clear characterization of the characters” (Review Madama Butterfly, stage director Damiano Michieletto, OperaClick, 2012).

Hypothesis 1 (H1).Opera houses' robust interpretations of tradition increase appeal to audience members.

This interpretation not only updated the traditional Mozartian material by transposing it temporally but also moved away from the dramaturgy of the original opera by updating the libretto.8 It is usually motivated by opera houses' desire to make strong identity claims about their unique positioning outside the boundaries of mainstream culture. Yet it is a challenging approach to follow and, according to several of our informants, it risks being penalized by opera goers. Two artistic directors, in particular, noted:“The young and already acclaimed director, free of reverential fears, enjoys updating the work of Mozart, bringing it down to a realistic, deliberately vulgar and irreverent dimension […] the connection with Mozart's original work is reduced to a minimum: there is no longer any trace of the ‘oriental’ color; the fabulous dimension of the work, with all its load of dreams, games and melancholy; even the text, despite the adjustments made, is often incongruent with respect to what we see” (Review of Il Ratto del Serraglio, stage director Damiano Michieletto, Il Giornale della Musica, 2009).

“When the reinterpretation has a strong dialectic character and revises the original work in a profound way (with a heated proposition of new themes), the audience become disoriented, frustrated and express their dissent vigorously” (Artistic Director Opera House # 7).

When contextualized within the language of schema theory, these observations suggest that radical interpretations are less likely to fit with any available schemas and more likely to elicit perceptions of incomprehensibility because they encapsulate novel dramatic content into novel product forms (Mandler, 1982; Meyers-Levy & Tybout, 1989). A change in core operatic features, usually accompanied by changes in visual ones, makes it harder for opera goers to draw analogies between their general schemas for the operatic tradition and its reinterpretation. Unlike robust interpretations, in this case, existing schemas cannot be easily extended to resolve the incongruity due to the lack of core features on which the evaluation can be anchored (Gentner, 1983; Gregan-Paxton & John, 1997). For this reason, radical interpretations produce a level of incongruity that can be viewed as unwarranted: while they allow for novel experiences, the efforts needed to resolve that incongruity do not seem justified. The more the novelty-induced stimulus is incongruous with existing schemas, the more intense is the emotional reaction it tends to elicit (Rindova & Petkova, 2007). To the extent that a strong experience of incongruity interferes with audiences' ability to cope with and benefit from novelty, radical interpretations are unlikely to elicit positive emotional reactions and increase perceived value. Accordingly, we hypothesize:“The audience are not baffled by the stage director's updating effort. […] they are baffled by modern reinterpretations that prevent them from understanding the text and no longer tell them what is going on. In this case the reinterpretation overlaps with, alters and transforms the text” (Artistic Director Opera House # 1).

Hypothesis 2 (H2).Opera houses' radical interpretations of tradition decrease appeal to audience members.

Generic schemas develop at the collective level and reflect a collective consensus about the institutionally codified features of a particular tradition. However, individuals may vary in the extent to which they make use of those generic schemas and, therefore, in their relative preference for and ability to cope with novelty. As an analogy, consider the context of technology adoption. Here lead users are likely to experience less incongruity for the same level of product novelty than mainstream customers. Indeed, they are more likely than mainstream customers to resolve this incongruity and form a more positive perception of value.9 This heterogeneity in the use of available evaluative schemas can be particularly pronounced across substantively different audiences—for example, critics and customers (see for instance Kim & Jensen, 2011) or domestic and foreign consumers (Kim & Jensen, 2014)—and sometimes can also characterize members of the same audience. As Cattani, Falchetti, and Ferriani (2020, p. 21) pointed out, “any given audience […] is never fully homogenous but usually consists of groups or segments that can embrace rather different standards and norms by which novelty is evaluated.”10

“If by competence we mean greater knowledge of the history of a particular opera and its various interpretations seasonal ticket holders are generally more competent” (Artistic Director # 3).

“Obviously, a subscriber who has been following the theatrical seasons for several years and attends 5–6 operas per season has a greater awareness than a more occasional audience” (Artistic Director # 2).

“Subscribers are typically the ‘faithful’ in the sense that they are those who decide to annually renew a season ticket” (Artistic Director # 8).

“Season-ticket holders are on average more competent. Their competence is not technical but derives from their experience and the habit of going to the opera […] the preparation of this audience stems from a cultural background that creates a basic training and is enhanced by the fact of going to the opera very often as a social rite […] season-ticket holders have an experiential competence” (Artistic Director #13).

In contrast, single-ticket holders are usually one-time customers with a lower commitment to the operatic world, less experience, and, therefore, less competent (Voss et al., 2006; Voss et al., 2008). As one artistic director emphasized:“Season-ticket holders […] over the years have acquired a knowledge of traditional repertoires and therefore are more familiar with them” (Artistic Director # 14).

Both audience segments are vital for the survival of opera houses. Yet they appear to vary significantly in their disposition toward operatic tradition. For instance, when asked about potential heterogeneity in opera goers' preferences, our informants evoked differences in openness to experimentation, connoisseurship, and underlying motivations. Several of our informants also pointed out that season-ticket holders are especially mindful of innovations that do not disrupt their more cultivated understanding of the operatic tradition. This may require more patience and gradualism on the part of the opera houses wishing to experiment:“Single ticket holders are less inclined to develop a ‘stable’ relationship with the opera house because they are less interested in this form of entertainment […] they are also less competent because they have seen fewer things, fewer versions of the same opera and, therefore, they may be more open to novelties […]” (Artistic Director # 3).

“Season-ticket holders want innovation (but) they are more conservative and biased because they already have a vision and knowledge of what they are going to see. Therefore, they are less willing to accept radical changes” (Stage Director # 3).

At the same time, season-ticket holders can be unforgiving with innovations that challenge their connoisseurship (Martorella, 1982). Interestingly, in recalling controversial cases of radical alterations to operatic classics, some of the artistic directors we interviewed explicitly referred to season-ticket holders as a crucial source of resistance:“Seasonal ticket holders are on average more resistant to novelty. However, I am happy to say that they have embarked on a path that makes them more open to innovation […] We have accompanied them in this journey and we have not provoked them, we have explained ourselves and we have tried to seduce them, to bring them on board” (Artistic Director Opera House # 5).

“As season ticket holders are more competent, they are more likely to recognize and sanction strong alterations. Since they know the original version of a particular opera, the different interpretations that characterize its evolution they are also more competent in that they have more information to judge a new interpretation. As a result, they are also less likely to appreciate radical changes” (Artistic Director # 3).

“Season-ticket holders are less open to innovative directions that distort established ways of presenting traditional operas” (Artistic Director #14).

Unlike season-ticket holders, single-ticket holders were often described as “curious,” “open,” “risk-tolerant,” and were generally perceived by our informants as being relatively more comfortable with new experiences, fresh stimuli, and highly contemporary stage directions. Four, in particular, emphasized:“We recently made a Verdi's Rigoletto in which the deformity of the protagonist has been moved to a timeless condition. Rigoletto has also been represented as a different man who provokes and astounds people […]. Season-ticket holders have sanctioned us; they have not forgiven us” (Artistic Director Opera House # 4).

“It is clear that traditional spectators like season-ticket holders have more prejudices because they already have their own vision and knowledge and are therefore less willing to accept upheavals and radical changes […] single ticket buyers are somewhat more ‘virgin’” (Director # 9).

“Single-ticket buyers are akin to novices or customers who come to the opera house once a year and are open to both hyper-traditional and hyper-contemporary stage directions […] they appreciate radical interpretations because they have fewer points of reference and they start from a less ideological point of view […] Accordingly they can evaluate radical innovations without being biased by previous judgments” (Artistic Director # 13).

“Single-ticket operagoers are more willing to move and attend performances offered by different theaters. They prefer diversity and want to be able to see more things differently” (Artistic Director Opera House # 8).

In light of these interviews, revisiting the theoretical arguments on the relationships between robust/radical interpretation and audience appeal developed in the first two hypotheses indicates the existence of an audience-based moderation. Conceptually, this moderation hinges primarily on the observation that the psychological processes involved in the perception of value vary across audiences as a function of their domain-specific knowledge (Falchetti et al., 2022; Moreau et al., 2001; Rottman et al., 2012). Since a robust interpretation does not disrupt the tradition's core features, season-ticket holders can more readily transfer their familiar understanding of a particular operatic tradition to its reinterpreted version. In the language of schema theory, expertise in the base domain translates into expertise in the target domain, making it easier to resolve novelty-driven incongruities. This idea is consistent with research in consumer behavior showing that expert consumers face lower learning costs than novices in understanding a novel item in an existing category (Alba & Hutchinson, 1987; Einhorn & Hogarth, 1981). By contrast, radical interpretations alter core features in the base domain, thus preventing experts from easily drawing analogies from a familiar domain to the target domain. As they strive to map the two domains, experts are more likely to recognize the dissimilarities between them, making the incongruity particularly notable. It could be argued that the same deep knowledge structures that increase season-ticket holders’ appreciation for robust interpretations also reduce their appreciation for radical ones.“Single-ticket holders […] may be those who go to the theater with curiosity or to see something new or simply with the desire to receive suggestions and new stimuli” (Artistic Director Opera House # 3).

Unlike season-ticket holders, single-ticket holders tend to have a less-complex and sophisticated understanding of the operatic tradition. As such, they rely more on visible attributes to find similarities between a given base domain (i.e., the traditional opera) and the new domain (i.e., the reinterpreted opera). As robust interpretations preserve core features of traditional operas but modify peripheral elements through visual adjustments, single-ticket holders may find it relatively harder than season-ticket holders to resolve the initial incongruity. Yet the lack of elaborate knowledge and deep-seated expectations that usually distinguish single-ticket holders also implies that they may not recognize as many discrepancies in constructing their mapping of the attributes from the base to the new domain (Fiske et al., 1983). Lacking the expertise of season-ticket holders, single-ticket holders will experience a lower level of incongruity when contrasting and comparing traditional material with its radical interpretation. Moreover, to the extent that single-ticket holders are more willing to experiment, as our fieldwork seems to indicate, they may not only experience fewer incongruities than season-ticket holders when faced with radical interpretations, but be more likely to form positive perceptions of value. Collectively, the above qualitative evidence and theoretical arguments lead us to expect relative differences in the intensity of season- and single-ticket holders' responses to robust and radical interpretations of tradition, as per our previous hypotheses. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 3a (H3a).Audience composition moderates the positive effect of opera houses' robust interpretations of tradition on audience appeal so that the effect is likely to be stronger for season-ticket than for single-ticket holders.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b).Audience composition moderates the negative effect of opera houses' radical interpretations of tradition on audience appeal so that the effect is likely to be stronger for season-ticket than for single-ticket holders.

4 EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

4.1 Sample and data

We collected data on the opera productions staged by the major Italian nonprofit opera houses from the artistic season 1989–1990 to the artistic season 2010–2011. From the artistic seasons of the sampled theaters, we excluded musicals, operettas, and concert-operas. Italian opera houses adopt a stagione (season) model, that is, the production of a number of operas that run independently for a few days every year.12 We focused on 42 nonprofit organizations staging operas classified according to the official classification of the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage.13 The data collection followed a three-step procedure. First, for each opera staged by the sampled theaters over the study period, we gathered information on its title (e.g., La Traviata, La Bohème, Don Giovanni), composer (e.g., Verdi, Puccini, Mozart), music style (Baroque, Classic, Romantic, Modern, and Contemporary) and number of production reruns.14 Second, we collected data on the characteristics of each opera production, in particular, the type of staging, the production process, the artists involved, and the number and type of tickets sold (season and single tickets). Finally, we collected information on the staging theaters including their status, funding sources, and seating capacity.15 Overall, our statistical analysis includes 2,627 useful observations. We collected most of our data manually from the magazine Annuario EDT/CIDIM of the Italian Lyric Opera. Widely regarded as the top Italian industry reference for opera, the Annuario is compiled under the supervision of the Italian National Musicological Committee. Published every year, it provides artistic and economic information about the operas performed by all Italian opera houses. It also displays photos of all the operas produced every year, thus creating a visual repertoire of images of each opera staging.

4.2 Dependent variable

“Our public is well informed because we communicate with them before the performance […] Transparency and correctness in providing information are fundamental. We do an impressive amount of preparatory works including meetings with the artists, lectures, readings and interviews with the artists and this is especially true when the opera is actualized” (Artistic Director # 2).

Season-ticket holders acquire information on the operas in their season package thanks to their proximity to the operatic world, network of contacts, peers opinions, reviews, and so forth. Thus, they learn in advance about an opera production's innovative artistic features and whether these features may appeal to them:“Opera goers are aware of the show they are going to see. This is true for both the segment of opera experts and for less prepared attendees who have the curiosity to attend an operatic production which is such a complex and fascinating show” (Artistic Director # 8).

Thus, regardless of the number of season-tickets sold, the actual attendance of opera goers usually varies across productions staged by a given opera house.17 For instance, season-ticket holders may decide to not attend some of the productions in their package if these productions do not meet their preferences and expectations. As the artistic directors of two important Italian theaters pointed out:“Season-ticket holders know if they should expect something different or if they will like the show or not […] they acquire information on a particular production by reading interviews with stage directors and conductors, by attending rehearsals […] or through contacts with other fans and artistic circles. Normally, information about a particular production circulates in advance through rehearsals, artists' circles and people who work in the theatre” (Artistic Director # 3).

“Season-ticket holders may choose not to attend some performances of the package they bought. They may subscribe for reasons of convenience and preemption on seats and then renounce to attend two or three performances if they have risky directions or unusual titles […] The reason is that season-ticket holders may vary in their preferences for some type of operas and stage directions” (Artistic Director # 2).

“If season-ticket holders are not attracted by a particular title or do not expect a high-quality production, they may not show up at the theater even if they bought a package especially if they have a more attractive alternative to spend that night” (Artistic Director # 3).

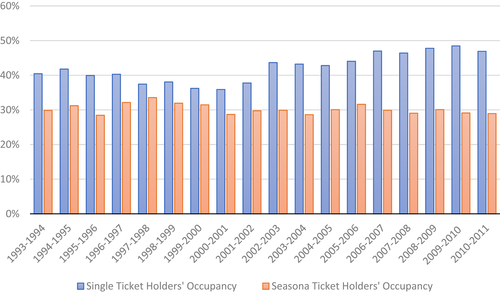

Figure 1 reports the average single- and season-ticket holders' occupancy per season, which was measured by dividing the total number of single- and season-ticket holders' admissions by the total number of available tickets (seating capacity). Note that while opera houses have traditionally tried to accommodate season-ticket holders due to the importance of season-ticket recurring revenue (Kim & Jensen, 2011; Martorella, 1982), their occupancy rate is on average lower than the one of single-ticket holders. In fact, in our sample, opera houses' seating capacity was mainly occupied by singlet-ticket buyers, confirming the growing strategic importance of this segment. Also, as a theoretical possibility, season-ticket holders could limit single-ticket holders' occupancy by preempting seats; yet there are no cases in which opera houses fill 100% of their seating capacity. Even after considering single-ticket holders, the seating capacity is never filled except for one opera house that did so only on three occasions.18 Over the study period, the average occupancy was 72% of the seating capacity (the median 75% and the standard deviation 0.194).“Season-ticket holders may decide not to attend the productions included in their packages if they do not like the title, the singer or the stage direction” (Artistic Director # 13).

4.3 Independent variables

4.3.1 Robust interpretation

Following previous research (Savage, 1994; Gossett, 2008), we considered opera productions that interpret traditional operas through innovative staging dimensions and alter taken-for-granted visual attributes as robust interpretations. We use the term traditional operas for all operas characterized by pre-twentieth century music styles and dramatic contents. All operas whose composers were born before 1881 were classified as traditional operas as they display a tonal music system and traditional narrative standards. Traditional operas can undergo a process of “modern displacement,” whereby the temporal and spatial coordinates of the text are either situated in a twentieth- or twenty-first century setting, or placed in a-temporal and abstract visual contexts. Examples include modern performances of Macbeth taking place in an airport terminal, La Bohème at a ski resort, and Rigoletto in a timeless and bare modern setting. We created a dummy variable that is equal to 1 if the opera is a robust interpretation, and 0 otherwise. We identified robust interpretations following a two-step procedure. First, we read the plots of each opera in the original formulation of their temporal and spatial characteristics. To this end, we relied on the Opera Book by Kobbe (1967), a very authoritative source that details the plot of more than 500 operas. Next, we analyzed and hand-coded the visuals of all operas that the sampled theaters produced over the period 1993–2010 (more precisely, from the artistic season 1993–1994 to the artistic season 2010–2011) based on the Annuario EDT/CIDIM. Robust interpretations differ from traditional interpretations in that the former transform the original temporal and spatial coordinates of existing operas, while the latter reproduces them faithfully.19

4.3.2 Radical interpretation

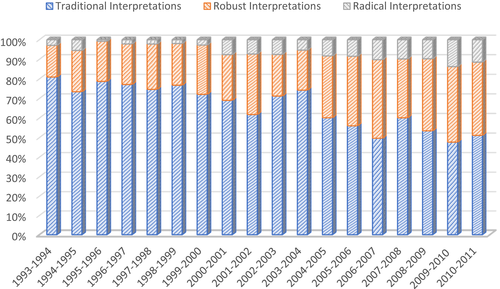

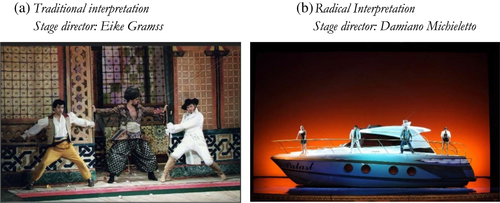

We considered as radical interpretations those opera productions that not only alter traditional operas' visual dimensions, but also change their established dramaturgic contents.20 We define a dramaturgic change as a change in the storyline or the actions and characterization of the protagonists. To identify dramaturgic changes, we compare the original stories and characters, as specified in the seminal book by Kobbe (1967), with those presented on stage after reading the reviews of each opera production published in the Annuario and specialized websites (OperaClick, GBOpera, il Giornale della Musica, L'Ape Musicale, and Liricamente). We then created a dummy variable that is equal to 1 if the opera is a radical interpretation, and 0 otherwise.21 Figure 2 shows the percentage of traditional, robust, and radical interpretations in our sample. Figures 3 and 4 show examples of some of the images we collected to classify operas as robust and radical interpretations, respectively.

4.4 Control variables

It is likely that other factors might influence the appeal of an opera production. Thus, we included several control variables to rule out alternative explanations for our results. By conferring prestige to an opera production, theater status acts as a signal of quality that may affect attendance. We measured the (high) status of a theater as a dummy variable (Opera House Status) that is equal to 1 if an opera house is a LSF (Lyric and Symphonic Foundation), and 0 otherwise. Indeed, LSFs are noted for their prestigious opera seasons and, as Law no. 800 of August 14, 1967 (known as the Crown law) specifies, are opera houses of “outstanding general interest, in promoting musical, cultural and social awareness in the nation.”

We controlled for the popularity of a composer (Composer Popularity) by examining the number of productions of his operas staged by the sampled theaters. Our fieldwork revealed that composer popularity may influence opera goers' decision to attend an opera because of the attractiveness of highly prominent composers who are strongly representative of the Italian operatic tradition. Specifically, we counted the number of times all the opera companies brought the operas of a composer on stage during the four artistic seasons before the current one.22 The higher (lower) the index, the higher (lower) the composer's popularity. The first year in our statistical analyses is 1993 (artistic season 1993–1994) and the corresponding popularity measure refers to the years 1989–1992. We also controlled for the presence of different music styles because some of them are more popular than others (Kim & Jensen, 2011; Martorella, 1977). To this end, we created a binary variable for each style that takes the value 1 if an opera belongs to that style, and 0 otherwise. Specifically, we considered the following styles: baroque (1600–1750), classic (1750–1820), early and mid-late romantic (1820–1920), and modern and contemporary (1920–nowadays). Styles are mutually exclusive in that operas embrace only one style (Heilbrun, 2001).

In the opera field, a co-production alliance is formed when one theater collaborates with another to develop and finance an opera production jointly. Coproductions affect attendance because they act as a preattendance signal of product quality. Accordingly, we created a binary variable (Coproduction) that is equal to 1 if the opera was coproduced with other theaters, and 0 otherwise. A new staging is characterized by visual attributes (e.g., set design, costumes, and stage directions) that no other opera house has ever presented before. A new staging may influence attendance by attracting the attention and curiosity of prospective opera attendees for the visual features of the production. We control for the effect of new staging by creating a binary variable (New Staging) that is equal to 1 if the opera is a new staging, and 0 otherwise.

The stage director is one of the artistic leaders of an opera production. We control for the eclecticism and popularity of the stage director because they can influence attendance by determining opera attendees' perception of the status and popularity of opera productions.23 We considered eclectic those directors who are simultaneously field insiders and active in at least one popular cultural genre. To account for the effect of stage directors' eclecticism, we created a binary variable (Director Eclecticism) that is equal to 1 if the stage director is eclectic, and 0 otherwise. We control for the popularity of the stage director (Director Popularity) by examining the number of productions each individual artist directed in the past—that is, during the previous three artistic seasons. We also account for the reputation of the conductor (Conductor Reputation), the figure responsible for the musical aspects of the production, by examining whether she/he won the Abbiati Prize24 in the “Best Conductors” category. We use a dummy variable (Summer Opera) to account for any differences between regular and summer opera productions (i.e., those staged during summer festivals and other initiatives) because a large portion of summer opera attendees are visitors who tend to be less interested in buying season tickets (Kim & Jensen, 2011). Theaters with a wider repertoire size dispose of a larger amount of financial resources to produce operas of better quality, innovate, and promote their artistic seasons. They can also schedule more operas of different styles, which may in turn affect attendance. We measure this variable (Repertoire Size) as the number of opera productions each theater staged in a given season. We finally included dummies for each artistic season in the model to control for macroeconomic trends and other time-invariant effects.

4.5 Estimation strategy

We tested our hypotheses by estimating three-level mixed-effect linear regression models, which include both fixed and random effects. Because opera productions are nested within individual operas (La Traviata versus La Wally) and individual operas are nested within opera companies, we considered the opera production as level 1, the individual opera (or title) as level 2, and the opera company as level 3. We obtained our estimates using STATA version 13. We report Huber–White robust standard errors to control for any residual heteroscedasticity across panels.

5 RESULTS

The descriptive statistics and correlation values for our measures are presented in Table 1. We checked whether multicollinearity is affecting our estimates by computing the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each model and found that the highest VIF statistics were below the recommended value of 10 (Hair et al., 1995), suggesting that multicollinearity is not an issue.

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Single tickets | 2,984.601 | 3,288.407 | 0 | 24,098 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 2 | Seasonal tickets | 2,375.396 | 2,481.029 | 0 | 13,267 | 0.372 | 1.000 | |||||

| 3 | Robust interpretation | 0.278 | 0.448 | 0 | 1 | −0.022 | 0.179 | 1.000 | ||||

| 4 | Radical interpretation | 0.067 | 0.250 | 0 | 1 | 0.122 | −0.046 | −0.166 | 1.000 | |||

| 5 | Composer popularity | 71.916 | 63.665 | 0 | 219 | 0.179 | 0.011 | −0.074 | 0.070 | 1.000 | ||

| 6 | Theater status | 0.441 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 | 0.539 | 0.581 | 0.104 | 0.044 | −0.063 | 1.000 | |

| 7 | New staging | 0.411 | 0.492 | 0 | 1 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.016 | 0.014 | −0.117 | 0.072 | 1.000 |

| 8 | Coproduction | 0.372 | 0.483 | 0 | 1 | −0.267 | −0.297 | 0.042 | 0.062 | 0.034 | −0.315 | −0.074 |

| 9 | Director eclecticism | 0.242 | 0.428 | 0 | 1 | 0.084 | −0.006 | −0.018 | −0.009 | 0.038 | 0.017 | −0.079 |

| 10 | Director popularity | 5.427 | 6.477 | 0 | 42 | 0.005 | 0.003 | −0.009 | −0.024 | 0.108 | −0.019 | −0.081 |

| 11 | Conductor reputation | 0.093 | 0.291 | 0 | 1 | 0.312 | 0.091 | 0.008 | 0.066 | 0.009 | 0.200 | 0.064 |

| 12 | Baroque | 0.046 | 0.210 | 0 | 1 | −0.107 | −0.120 | 0.033 | 0.013 | −0.235 | 0.023 | 0.091 |

| 13 | Classic | 0.138 | 0.345 | 0 | 1 | −0.046 | −0.053 | 0.037 | −0.046 | −0.203 | −0.042 | 0.008 |

| 14 | Mid and late Romantic | 0.567 | 0.496 | 0 | 1 | 0.132 | 0.108 | −0.023 | 0.053 | 0.397 | 0.037 | −0.036 |

| 15 | Modern and contemporary | 0.025 | 0.157 | 0 | 1 | −0.055 | −0.034 | −0.100 | −0.043 | −0.178 | 0.053 | 0.054 |

| 16 | Summer opera | 0.031 | 0.173 | 0 | 1 | −0.076 | −0.161 | −0.111 | −0.013 | −0.042 | −0.158 | 0.142 |

| 17 | Repertoire size | 5.770 | 2.462 | 1 | 14 | 0.470 | 0.409 | 0.053 | 0.069 | −0.053 | 0.655 | 0.080 |

| Variables | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Single tickets | ||||||||||

| 2 | Seasonal tickets | ||||||||||

| 3 | Robust interpretation | ||||||||||

| 4 | Radical interpretation | ||||||||||

| 5 | Composer popularity | ||||||||||

| 6 | Theater status | ||||||||||

| 7 | New staging | ||||||||||

| 8 | Coproduction | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 9 | Director eclecticism | −0.003 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 10 | Director popularity | 0.014 | 0.124 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 11 | Conductor reputation | −0.060 | 0.042 | −0.003 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 12 | Baroque | 0.040 | −0.023 | −0.038 | −0.071 | 1.000 | |||||

| 13 | Classic | 0.005 | 0.057 | −0.036 | 0.065 | −0.088 | 1.000 | ||||

| 14 | Mid and late Romantic | −0.015 | −0.082 | 0.001 | 0.061 | −0.253 | −0.458 | 1.000 | |||

| 15 | Modern and contemporary | 0.012 | −0.017 | −0.006 | −0.001 | −0.035 | −0.064 | −0.184 | 1.000 | ||

| 16 | Summer opera | −0.096 | −0.065 | −0.046 | −0.050 | −0.008 | 0.024 | −0.018 | −0.029 | 1.000 | |

| 17 | Repertoire size | −0.201 | 0.004 | −0.024 | 0.194 | 0.048 | −0.037 | 0.013 | 0.110 | −0.220 | 1.000 |

Table 2 reports the results of a first set of multilevel mixed-effect linear regression models in which the natural logarithm of the total theater attendance is the dependent variable. Although the coefficients are not displayed, all models include year dummies. In Model 1 and in Model 2, we entered the variables of theoretical interest measuring, respectively, robust and radical interpretations separately, and in Model 3 both variables together. We used traditional interpretation as the reference category. From these models, there is preliminary evidence that, consistently with Hypothesis 1, robust interpretations have the expected positive effect on attendance; contrary to Hypothesis 2, however, radical interpretations have a positive rather than the expected negative effect on attendance. Model 4 is a baseline model with only the controls. The model estimates suggest that an opera production is more likely to appeal to opera goers when the staging theater has (high) status and when it is directed by eclectic artists. Operas by highly popular composers are more likely to be positively recognized by opera goers and the stage director popularity increases attendance as well. An opera production characterized by a baroque or contemporary music style is less appealing to opera goers than a production with a romantic music style. Coproduced operas are also less attractive. Model 5 (our full model) includes the variables of theoretical interest—robust and radical interpretation—and the controls. As the results indicate, the relationship between robust interpretation and the total theater attendance is positive (β = .087; p value = .000). In line with our theory, robust interpretations are more likely than traditional interpretations to appeal to opera goers, thus supporting Hypothesis 1. Since the dependent variable is expressed in logarithmic form, we can convert the coefficients of the explanatory variables into percentage changes by applying the following transformation 100 × (ex − 1). When the variable robust interpretation is equal to 1 as opposed to 0 (traditional interpretation) attendance increases by 9.1%. The relationship between radical interpretation and theater attendance is also positive—rather than negative as predicted—suggesting that radical interpretations are more likely to appeal to opera goers than traditional interpretations (β = .131; p value = .001). Again, when the variable radical interpretation is equal to 1 as opposed to 0 (traditional interpretation) attendance increases by 14%. Therefore, hypothesis 2 is not supported. A chi-square inequality test indicates that there is no difference between the coefficients of the two variables (χ2 = 1.15, with p value = .283), confirming that robust and radical interpretations are equally important in driving attendance. The overall fit of the model improves substantially, as indicated by the LR test (χ2[L5–L4 = 22.31, with p-value <.001 for 2 d.f.) and the AIC test (3,688.866 vs. 3,670.556), when we compare the full model with the model with only the controls.

| Dependent variable: Total theater attendance (log) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Robust interpretation | 0.055 (.004) | 0.074 (.001) | 0.087 (.000) | 0.085 (.000) | 0.083 (.000) | ||

| Radical intepretation | 0.143 (.008) | 0.169 (.003) | 0.131 (.001) | 0.128 (.002) | 0.128 (.002) | ||

| Composer popularity | 0.001 (.000) | 0.001 (.000) | 0.001 (.000) | 0.001 (.000) | |||

| Theater status | 1.407 (.000) | 1.393 (.000) | 1.358 (.000) | 1.748 (.000) | |||

| New staging | 0.028 (.347) | 0.024 (.419) | 0.020 (.499) | 0.018 (.538) | |||

| Coproduction | −0.078 (.004) | −0.085 (.002) | −0.082 (.008) | −0.075 (.015) | |||

| Director eclecticism | 0.108 (.000) | 0.108 (.000) | 0.116 (.000) | 0.117 (.000) | |||

| Director popularity | 0.003 (.010) | 0.003 (.007) | 0.002 (.131) | 0.002 (.136) | |||

| Conductor reputation | 0.071 (.257) | 0.068 (.274) | 0.031 (.572) | 0.029 (.602) | |||

| Baroque | −0.669 (.000) | −0.666 (.000) | −0.674 (.000) | −0.671 (.000) | |||

| Classic | −0.072 (.161) | −0.068 (.173) | −0.050 (.305) | −0.048 (.324) | |||

| Mid and late Romantic | 0.056 (.027) | 0.056 (.024) | 0.073 (.002) | 0.073 (.002) | |||

| Modern and contemporary | −0.349 (.012) | −0.302 (.024) | −0.295 (.033) | −0.293 (.035) | |||

| Summer opera | −0.173 (.237) | −0.150 (.297) | −0.088 (.489) | −0.206 (.000) | |||

| Repertoire size | −0.020 (.041) | −0.020 (.045) | −0.022 (.038) | −0.023 (.028) | |||

| Performers' status | 0.165 (.000) | 0.162 (.000) | |||||

| Time dummies | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| _cons | 7.869 (.000) | 7.877 (.000) | 7.867 (.000) | 7.436 (.000) | 7.422 (.000) | 7.440 (.000) | 7.479 (.000) |

| Log Pseudo-Likelihood | −2079.569 | −2076.399 | −2071.519 | −1810.432 | −1799.278 | −1,602.233 | −1,516.773 |

- Note: p values in parenthesis. Traditional interpretations are the comparison interpretation category. Early Romanticism is the comparison music style. Time dummies (Yes). 2,627 observations. Standard errors are heteroskedastic-consistent (robust). Performers' status and theater fixed effects are included in Model 7 (2,346 observations).

We also re-estimated our full model by including the status of the three main performers (Model 6) as the latter is an important factor influencing opera goers' decision to attend an opera. Specifically, we entered a composite status variable that was coded 0 if none of the three lead performers won the Abbiati Prize in the “Best Singers” category, 1 if at least one of them won the Prize, and 2 if more than one of them won it. We estimated a separate regression model with the performers' status control because data on this variable were not available for all the artistic seasons in the database. The results did not change appreciably when we controlled for the status of the lead performers. We then re-estimated the full model after including the control for the status of the lead performers and theater fixed effects. The results, which are reported in Model 7, were consistent with those reported in Models 5 and 6.

The arguments leading to Hypotheses 3a and 3b rest on the assumption that opera goers do not form a homogeneous group but can be divided into two main segments: season- and single-ticket holders. Before testing both hypotheses, therefore, it is important to show that the two groups differ along some key dimensions that explain why they prefer one or the other type of interpretation of traditional operas. To this end, we estimated separate models for season- and single-ticket holders. Given the nature of our data, we are unable to introduce unobserved heterogeneity directly into the regression models. However, our data allow us to relate attendance (the dependent variable) to either segment to some of the most salient characteristics of the opera house, the title, the composer, the director, the type of interpretation, and so on. Interestingly, even our informants identified these characteristics as relevant in explaining the preference of opera goers for robust or radical interpretations of tradition.

Tables 3 and 4 present the results of the multilevel mixed-effect linear regression models for season- and single-tickets holders, respectively. In particular, Models 8–14 in Table 3 report the effects of robust and radical interpretation on season-ticket attendance, and Models 15–21 in Table 4 report the same effects on single-ticket attendance.

| Dependent variable: Seasonal ticket attendance (log) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 | Model 14 | |

| Robust interpretation | 0.181 (.000) | 0.180 (.000) | 0.195 (.000) | 0.199 (.000) | 0.195 (.000) | ||

| Radical intepretation | −0.078 (.093) | −0.011 (.830) | −0.031 (.574) | −0.015 (.796) | −0.016 (.776) | ||

| Composer popularity | −0.000 (.432) | 0.000 (.997) | −0.000 (.772) | −0.000 (.794) | |||

| Theater status | 1.556 (.000) | 1.533 (.000) | 1.479 (.000) | 2.021 (.000) | |||

| New staging | 0.021 (.658) | 0.015 (.745) | 0.015 (.749) | 0.014 (.761) | |||

| Coproduction | 0.037 (.409) | 0.029 (.492) | 0.025 (.537) | 0.031 (.441) | |||

| Dirctor eclecticism | −0.006 (.844) | −0.002 (.929) | −0.006 (.842) | −0.004 (.879) | |||

| Director popularity | 0.005 (.000) | 0.005 (.000) | 0.004 (.001) | 0.004 (.001) | |||

| Conductor reputation | −0.047 (.363) | −0.048 (.333) | −0.067 (.200) | −0.067 (.192) | |||

| Baroque | −0.771 (.003) | −0.778 (.002) | −0.789 (.002) | −0.785 (.002) | |||

| Classic | −0.014 (.634) | −0.016 (.624) | −0.004 (.904) | −0.002 (.940) | |||

| Mid and late Romantic | 0.044 (.153) | 0.047 (.148) | 0.071 (.032) | 0.070 (.034) | |||

| Modern and contemporary | −0.128 (.407) | −0.053 (.744) | −0.043 (.795) | −0.042 (.801) | |||

| Summer opera | −0.817 (.000) | −0.778 (.000) | −0.848 (.000) | −1.131 (.000) | |||

| Repertoire size | −0.007 (.645) | −0.005 (.707) | −0.008 (.517) | −0.009 (.472) | |||

| Performers' status | 0.097 (.024) | 0.095 (.029) | |||||

| Time dummies | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| _cons | 6.929 (.000) | 6.960 (.000) | 6.930 (.000) | 6.514 (.000) | 6.475 (.000) | 6.430 (.000) | 6.714 (.000) |

| Log Pseudo-Likelihood | −2,436.606 | −2,454.488 | −2,436.585 | −2,368.455 | −2,344.651 | −2,115.535 | −2,024.992 |

- Note: p values in parenthesis. Traditional interpretations are the comparison interpretation category. Early Romanticism is the comparison music style. Time dummies (Yes). 2,459 observations. Standard Errors are heteroskedastic-consistent (robust). Performers' status and theater fixed effects are included in Model 14 (2,200 observations).

| Dependent variable: Single ticket attendance (log) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 15 | Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | Model 19 | Model 20 | Model 21 | |

| Robust interpretation | −0.080 (.007) | −0.057 (.071) | −0.042 (.090) | −0.056 (.030) | −0.056 (.030) | ||

| Radical intepretation | 0.230 (.001) | 0.209 (.002) | 0.162 (.001) | 0.151 (.002) | 0.149 (.002) | ||

| Composer popularity | 0.003 (.000) | 0.002 (.000) | 0.002 (.000) | 0.002 (.000) | |||

| Theater status | 1.232 (.000) | 1.234 (.000) | 1.233 (.000) | 1.258 (.000) | |||

| New staging | 0.049 (.113) | 0.048 (.119) | 0.041 (.183) | 0.038 (.219) | |||

| Coproduction | −0.133 (.000) | −0.136 (.000) | −0.124 (.003) | −0.117 (.005) | |||

| Director eclecticism | 0.136 (.000) | 0.135 (.000) | 0.150 (.000) | 0.151 (.000) | |||

| Director popularity | 0.000 (.796) | 0.000 (.726) | −0.000 (.865) | −0.000 (.845) | |||

| Conductor reputation | 0.105 (.223) | 0.103 (.218) | 0.052 (.470) | 0.044 (.550) | |||

| Baroque | −0.579 (.000) | −0.579 (.000) | −0.571 (.000) | −0.569 (.000) | |||

| Classic | −0.081 (.095) | −0.076 (.108) | −0.062 (.173) | −0.060 (.188) | |||

| Mid and late Romantic | 0.015 (.648) | 0.013 (.685) | 0.030 (.337) | 0.031 (.331) | |||

| Modern and contemporary | −0.429 (.004) | −0.430 (.002) | −0.413 (.003) | −0.412 (.003) | |||

| Summer opera | 0.283 (.228) | 0.272 (.233) | 0.377 (.035) | 0.057 (.101) | |||

| Repertoire size | −0.029 (.012) | −0.029 (.010) | −0.029 (.012) | −0.032 (.007) | |||

| Performers' status | 0.165 (.000) | 0.161 (.000) | |||||

| Time dummies | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| _cons | 7.250 (.000) | 7.239 (.000) | 7.247 (.000) | 6.813 (.000) | 6.823 (.000) | 6.804 (.000) | 6.911 (.000) |

| Log Pseudo-Likelihood | −2,701.511 | −2,695.666 | −2,693.905 | −2,466.023 | −2,458.471 | −2,178.905 | −2,104.533 |

- Note: p values in parenthesis. Traditional interpretations are the comparison interpretation category. Early Romanticism is the comparison music style. Time dummies (Yes). 2,623 observations. Standard errors are heteroskedastic-consistent (robust). Performers' status and theater fixed effects are included in Model 21 (2,342 observations).

In Models 8 and 9 (Table 3), we introduced robust and radical interpretation alone as independent variables, and in Model 10, we included both variables. Once again, we used traditional interpretation as the reference category. We did the same for Models 15, 16, and 17 (Table 4) where we examined the effects of robust and radical interpretation on single-ticket admissions. Model 11 (Table 3) and Model 18 (Table 4) are baseline models that include only the controls. Model 11 (Table 3) suggests that season-tickets holders find an opera production more appealing when the staging theater has (high) status and when the popularity of its stage director increases. The baroque music style, on the other hand, makes an opera production less appealing to season-ticket holders. Operas that are staged as part of summer festivals are also less appealing. Model 18 (Table 4) shows that an opera production is less likely to appeal to single-ticket holders when it is coproduced and when the staging theater has a large repertoire size. Single-ticket holders also find an opera production characterized by a baroque or contemporary music style less appealing than a production with an early romantic style. Conversely, operas composed by highly popular composers are more likely to be positively recognized by single-ticket holders.

In Model 12 (Table 3), the relationship between robust interpretation and season-ticket attendance is positive (β = .195; p-value = .000): when the variable robust interpretation is equal to 1 as opposed to 0 (traditional interpretation) attendance increases by 21.5%. In contrast, in Model 19 (Table 4), the relationship between robust interpretations and single-ticket attendance is negative (β = −.042; p-value = .090). In addition, the effect of radical interpretations on season-ticket attendance is negative, while its effect on single-ticket attendance is positive (β = .162; p-value = .001): when the variable radical interpretation is equal to 1 as opposed to 0 (traditional interpretation) attendance increases by 17.6%. The coefficients of the robust and radical interpretation variables are also different as indicated by the chi-square inequality tests performed after the estimation of Model 12 (χ2 = 12.61, with p-value .000) and Model 19 (χ2 = 16.25, with p-value .000). This suggests that robust and radical interpretations have unequal effects on the attendance of season- and single-ticket holders, respectively. The overall fit of the models improves substantially, as indicated by the LR tests (Model χ2[L10–L9 = 47.61 with p-value < .001 for 2 d.f.; Model χ2[L15–L14 = 15.10 with p-value < .001 for 2 d.f.) and the AIC tests (4,804.91 vs. 4,761.303; 5,000.047 vs. 4,988.942), when we compare the full models to those with the controls only. These results suggest that single-ticket holders' attendance could drive the positive effect of radical interpretations in the models estimating the total theater attendance (Models 5, 6, and 7 in Table 2). Season-ticket holders' attendance seems to drive the positive effect of robust interpretations on the total theater attendance (Models 5, 6, and 7 in Table 2): while robust interpretations increase season-ticket holders' attendance (Model 12 in Table 3), they reduce that of single-ticket holders (Model 19 in Table 4). These results were confirmed when we re-estimated Models 12 and 19 by including the status of the lead performers and theater fixed effects (Models 13 and 14 in Table 3 and Models 20 and 21 in Table 4).

From these analyses, it is clear that audience composition is important to explain opera goers' behavior. There is indeed evidence that season- and single-ticket holders differ along several important dimensions. In addition to the effects of robust and radical interpretation, the effects of other variables—coproduction, director popularity, director eclecticism, modern and contemporary, and summer opera—vary between the two segments of opera goers. These differences suggest that audience composition moderates the effect of opera houses' robust and radical interpretation of tradition on audience appeal. Accounting for these differences is critical for testing Hypotheses 3a and 3b—which predict differences in the intensity of season- and single-ticket holders' responses to robust and radical interpretations. Accordingly, we estimated combined models for both segments of opera goers (Cattani et al., 2014). This was essential to allow the unobserved heterogeneity to be common to season- and single-ticket holders. To distinguish the two audience segments, the combined dataset includes a variable dummy that takes the value 1 for the single-ticket segment and 0 for the season-ticket segment. We tested whether the effect of interpreting tradition varies between the two segments by entering two interactions terms into the models: one between dummy and robust interpretation, and the other between dummy and radical interpretation. We also included interactions between dummy and the above four variables—coproduction, director popularity, director eclecticism, modern and contemporary, and summer opera—to accommodate the apparent differences in effects of these variables in Tables 3 and 4. We estimated mixed-effects linear models.

Careful inspection of the main effects and interactions reveals that the results reported in Table 5 are quite similar to those in Tables 3 and 4. As Model 22 (Table 5) shows the interaction between dummy (that is equal to 1 for single-ticket admissions and 0 otherwise) and robust interpretations is negative (−0.417), while the interaction between dummy and radical interpretations is positive (0.394). These results provide support for Hypotheses 3a and 3b, confirming that season- and single-ticket holders vary in the intensity with which they respond to robust and radical interpretations of tradition: single-ticket holders are less likely to appreciate robust interpretations than season-ticket holders, while the opposite is true for radical interpretations. The two segments, however, seem to differ also in terms of other observed dimensions: single-ticket holders prefer to attend operas of popular composers, conducted by eclectic directors, and staged in the summer. Furthermore, there is some evidence that single-ticket holders appreciate modern operas less than season-ticket holders. Again, the results did not change appreciably when we controlled for the status of the lead performers and theater fixed effects (Models 23 and 24 in Table 5).

| Seasonal and single ticket attendance (log) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 22 | Model 23 | Model 24 | |

| Robust interpretation | 0.281 (.000) | 0.294 (.000) | 0.291 (.000) |

| Radical interpretation | −0.138 (.169) | −0.122 (.230) | −0.122 (.226) |

| Dummy (1 = single ticket) | 0.057 (.788) | 0.097 (.648) | 0.097 (.647) |

| Dummy × Robust interpretation | −0.417 (.000) | −0.448 (.000) | −0.448 (.000) |

| Dummy × Radical interpretation | 0.394 (.023) | 0.369 (.035) | 0.368 (.035) |

| Dummy × Coproduction | 0.053 (.752) | 0.043 (.803) | 0.042 (.805) |

| Dummy × Modern and contemporary | −0.286 (.092) | −0.282 (.100) | −0.282 (.100) |

| Dummy × Director popularity | −0.005 (.263) | −0.005 (.250) | −0.005 (.249) |

| Dummy × Summer opera | 1.034 (.000) | 1.193 (.000) | 1.172 (.000) |

| Dummy × Composer popularity | 0.003 (.000) | 0.003 (.000) | 0.003 (.000) |

| Dummy × Director eclecticism | 0.219 (.000) | 0.236 (.000) | 0.236 (.000) |

| Control variables | Included | Included | Included |

| Time dummies | Included | Included | Included |

| _cons | 6.663 (.000) | 6.611 (.000) | 6.804 (.000) |

| Log Pseudo-Likelihood | −5,660.7237 | −5,036.0763 | −4,952.4387 |

- Note: p values in parenthesis. Control Variables included. Traditional interpretations are the comparison interpretation category. Early Romanticism is the comparison music style. Time dummies (Yes). 5,082 observations. Standard Errors are heteroskedastic-consistent (robust). Performers' status is included in Model 23. Performers' status and theater fixed effects are included in Model 24 (4,542 observations).

5.1 Robustness checks

We further probed the previous results by estimating alternative model specifications. In all models, we controlled for the status of the lead performers and theater fixed effects. We first replicated the previous results by estimating multilevel mixed effect negative binomial regression models with the menbreg command in Stata (version 13) by maximum likelihood.

The results of these additional analyses are reported in Appendix S3. As shown in Model 25 (Table S1, Appendix S3), the coefficient for robust and radical interpretation are both positive, supporting the first two hypotheses. The results of the next two models (Models 26 and 27) provide evidence that season- and single-ticket holders differ along with the same dimensions observed in Tables 3 and 4. We also reported the incident rate ratios by specifying the IRR option in STATA for Models 25, 26, and 27 in Appendix S3: while robust interpretations increase season-ticket holders' attendance by 19%, radical interpretations increase single-ticket holders' attendance by 14.2%. The results reported in Model 28 (Table S2, Appendix S3) confirm those of the multilevel mixed-effect linear regression models (Table 5), further supporting Hypotheses 3a and 3b.

We also ran a series of supplementary analyses. Since not all theaters have the same size and can sell the same number of tickets, we started by estimating models in which the dependent variable also accounts for theater size. Specifically, we measured the dependent variable by dividing the total number of theater admissions (attendance) per opera production by the number of available tickets (occupancy). Following the lead of previous studies (e.g., Daigle & Rouleau, 2010; Gilhespy, 1999), we chose the occupancy because it captures an opera house's ability to fill its seating capacity by attracting different types of opera attendees. The new results corroborate the first two hypotheses: the occupancy per production is higher for both robust and radical interpretations (Model 29, Table S3 in Appendix S3) than for traditional interpretations (the reference category). We also estimated two models in which the dependent variables were expressed, respectively, as season- and single-ticket holders’ occupancy by dividing the total number of season- and single-ticket admissions (attendance) by the number of available tickets. The new results confirmed the previous results: season-ticket holders’ occupancy is higher (lower) for robust (radical) interpretations, while single-ticket holders’ occupancy is higher (lower) for radical (robust) interpretations (Models 30–31, Table S3, Appendix S3). To account for the effect of theater size on the appeal of robust and radical interpretations, we also entered the number of available tickets as a control variable into the full models (Models 32–34, Table S3 in Appendix S3). The results did not change appreciably.

Prior research in the opera industry (Kim & Jensen, 2011) has shown how, in the US context, opera houses have tried to increase the market appeal of their productions by changing the ordering between conventional and unconventional operas in their repertoire. We then re-estimated our models by controlling for the opera conventionality—that is, how frequently any given opera was staged in the previous 4 years. Since the opera conventionality control is highly correlated with the Composer Popularity control (i.e., the number of times all the opera companies staged the operas of a composer in the previous 4 years), we created a composite index that accounts for both the conventionality of the opera and the popularity of the composer. Specifically, we entered a composite conventionality variable that was coded 0 if neither the opera conventionality nor the composer popularity is higher than the 75th percentile, 1 if at least one of them is higher than the 75th percentile, and 2 if both of them are higher than the 75th percentile. The results (reported in Table S4, Appendix S3, Models 35–37) did not change appreciably.

We also directly compared the appeal of robust and radical interpretations on season- and single-ticket holders by estimating the full models using robust rather than traditional interpretations as the reference category (Models 38–40, Table S4 in Appendix S3). We found that season-ticket holders prefer robust to radical interpretations while the opposite is true for single-ticket buyers. These results further supported Hypotheses 3a and 3b.