Informal economy and central bank digital currency

Managing Editor: Steven Ongena

Abstract

This paper explores the association between the informal economy and the adoption of central bank digital currency (CBDC) by end users, namely households and businesses. Our findings suggest that CBDC may not be widely accepted by end users in the presence of a sizable informal economy in which cash is the primary method of payment. CBDC can decrease informality, but this effect becomes weaker in countries with larger informal economies. Tax reduction and CBDC interest rates can be useful tools to promote the adoption and effectiveness of CBDC, leading to a reallocation effect between formal and informal sectors.

Abbreviations

-

- ATM

-

- automated teller machine

-

- CBDC

-

- central bank digital currency

-

- DSGE

-

- dynamic stochastic general equilibrium

-

- ECB

-

- European Central Bank

-

- MIU

-

- money-in-utility

-

- OLS

-

- ordinary least squares

-

- TFP

-

- total factor productivity

-

- VAT

-

- Value added tax

1 INTRODUCTION

Technological advances in the digital economy have opened the possibility for central banks to issue digital fiat currency— Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC).1 Ongoing research has spurred a broad discussion about whether central banks should issue CBDC. Proponents argue that CBDC has lower transaction costs than cash (Griffoli et al., 2018), could avoid potential instability caused by private money creation (Brunnermeier & Niepelt, 2019), and improves macroeconomic management as well as the control of money2 (Bindseil, 2020). The main motivations for emerging economies are a broader tax base from limiting tax evasion and other illicit activities, as well as improved financial inclusion by allowing the unbanked to have access to electronic payment systems (Boar & Wehrli, 2021). Prior research has commonly focused on issuer-related perspectives of CBDC; however, little information is available on the preferences and motivations of consumers and businesses related to the adoption of CBDC. The goal of our paper is to assess the extent to which CBDC can be accepted by end users and circulated in the economy when end user's tax avoidance activities are taken into account, and how the use of CBDC impacts the informal economy.

We build a two-sector dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) model with formal and informal productions to understand the relationship between CBDC and the informal economy based on Fernández and Meza (2015) and Orsi et al. (2014). The end users value anonymity in transactions offered by cash payments, especially in countries where significant informal incomes discourage people from using digital payments for tax evasion.3 Following Agur et al. (2022), the CBDC in our model is designed to blend the characteristics of cash (i.e., peer-to-peer transactions) and the digital nature of deposits (i.e., interest rates). Compared with cash, CBDC is a more efficient means of payment because of lower transaction costs (Griffoli et al., 2018; Hasan et al., 2013; Kosse et al., 2017),4 but is subject to central bank monitoring and spillover effects on the enforcement of tax payments. Consequently, CBDC leads to a trade-off between cost efficiency and anonymity for households who determine the optimal allocation between cash and CBDC. This decision, in turn, affects labor allocation through the income gap between formal and informal sectors.

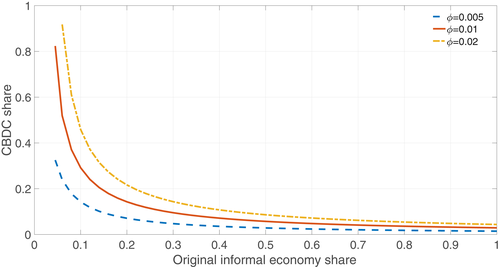

To quantitatively evaluate the implications of our model, we calibrate parameters for multiple cases, which allow us to conduct cross-country comparisons. Our results suggest an L-shaped relationship between the informal economy and CBDC, thereby implying that countries with large informal economies—typically developing countries—might be less likely to adopt and widely use CBDC. Moreover, we show a formalization effect on the informal sector due to the spillover effect of CBDC in detecting informal incomes. However, the magnitude of the formalization effect diminishes with the scale of the informal economy.

In order to simultaneously promote the adoption of CBDC and the formalization effect, we consider two policy tools—tax reduction and CBDC interest rates. A tax reduction weakens household incentives to evade taxes, leading to lower opportunity costs of detection when using CBDC. A positive CBDC interest rate directly increases incentives for households to hold CBDC. Both policies can encourage the adoption of CBDC. The increased CBDC share in money, in turn, leads to improved monitoring of informal earnings and thus strengthens formalization effects.

In light of model mechanisms, we apply the CBDC informal-economy relationship in a business cycle framework to study the implications of adjusting the CBDC interest rate for macroeconomic fluctuations. Following the impulse response analysis, we find that adjusting the CBDC interest rate triggers a reallocation effect between formal and informal sectors, which in turn leads to a more pronounced impulse response of formal output to policy shocks. Given counter-cyclical implementation of government policies, the CBDC rate adjustment could contribute to stabilization of measured business cycles. Such a finding, when combined with the effects of tax rate adjustment, suggests the importance of coordination between fiscal authorities and central banks in macroeconomic management. Moreover, we also show an efficiency gain from CBDC. When more CBDC is used in transactions, the aggregate transaction costs would be lower which, in turn, stimulates consumption.

Following the quantitative analysis, we further examine the welfare implications of CBDC based on different scenarios. Overall, the presence of CBDC leads to welfare gains by reducing transaction costs to stimulate consumption and by formalizing the economy so that labor forces can enjoy better social protection. The welfare enhancing effects could become larger if (i) we further account for the interactions between CBDC and stochastic disturbances, (ii) the share of the informal economy becomes small, and (iii) productivity gaps between formal and informal sectors become large. However, if users strongly prefer payment anonymity, the welfare gains could be significantly dampened.

This paper relates to the growing area of CBDC (e.g., Brunnermeier and Niepelt (2019); Fernández-Villaverde et al. (2020)). Focusing on the design of CBDC, Andolfatto (2021) and Agur et al. (2022) analyze factors that determine the demand for CBDC among different types of money. Based on DSGE models, a strand of literature analyzes implications of CBDC (Barrdear & Kumhof, 2016; Mehl et al., 2020; Uhlig & Xie, 2021) for monetary policies and open economy issues. By extending DSGE modeling of CBDC, our contribution is to highlight the demand for CBDC from the end-user perspective, with a greater focus on the trade-off between cost efficiency and anonymity in payments. Our study proposes the informal economy as another important determinator which affects CBDC through the anonymity feature. Although CBDC can reduce transaction costs by promoting financial inclusion, which is particularly important for developing countries, this benefit could be outweighed by households being in favor of informal incomes. As a result, it could be more difficult for developing countries than for developed countries to adopt CBDC, since informality is more pronounced in the former.

This study is also related to the literature on the informal economy. Existing literature suggests that the informal economy acts as an alternative source of growth and as a cushion in business cycles (Fernández & Meza, 2015; Loayza & Rigolini, 2011). However, the coexistence of formal and informal economies is only a second-best situation. Low productivity (Prado, 2011), lack of social protection (Orsi et al., 2014) and financial exclusion (Capasso & Jappelli, 2013) render informality an undesirable component of an economy. Moreover, the presence of informality causes measurement errors (Gomis-Porqueras et al., 2014; Restrepo-Echavarria, 2014) and weakens the propagation of government policies (Alberola & Urrutia, 2020). This paper contributes to the literature by highlighting how the introduction of CBDC is conducive to the formalization process not only in the long-run but also in a short-run business cycle framework, albeit the benefits are asymmetric across countries. Our findings also connect to interactions between the informal economy and fiscal or monetary policies. Building on Orsi et al. (2014) who find that a high tax rate stimulates the informal economy and Alberola and Urrutia (2020) who show that informality dampens the transmission of monetary policies, we show how adjusting the CBDC interest rate triggers a reallocation between formal and informal labor. We therefore complement the literature on how to improve the formalization effect of fiscal policies and bridge the gap regarding implications of monetary policies for the informal economy.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews some facts and motivational evidence followed by Section 3 that presents the model with CBDC and the informal economy. Section 4 presents our parameter calibrations and Section 5 uses the calibrated model parameters for steady-state analyses. In Section 6, the implications of the relationship between the informal economy and CBDC for business cycles is examined followed by Section 7 that examines the welfare implications of CBDC. Section 8 concludes with comments.

2 THE INFORMAL ECONOMY AND PAYMENTS

Cash is the crucial medium for undeclared monetized exchanges, as it is not traceable by public authorities in an informal economy. In this way, businesses can evade tax and social security contributions, and employees can avoid paying income taxes. However, cash payments aggravate the tax enforcement problem (Gordon & Li, 2009), which is one of the key aspects of the informal economy. The size of informal activities is larger in developing economies than in developed economies (Capasso & Jappelli, 2013), which is linked to cash being dominant in developing economies. This is despite the rapid development of financial innovation in developing countries (Bech et al., 2018) because cash provides anonymity for users which allows them to hide their transaction histories. For numerous reasons, such as tackling tax evasion and increasing financial inclusion, policymakers encourage the use of digital payments and have tried to change the payment behavior of individuals5. Most forms of electronic money or digital payments can be easily traced by public authorities. For instance, bank account records and the use of credit or debit cards have a high probability of detection as they can be cross-checked via third-party reporting. VAT invoice data and third-party reporting data enable tax authorities to identify and cluster taxpayers, which enhances tax evasion detection.

Among the inhibitors of the adoption of digital payments, the size of the informal economy plays a major role. To better understand the effect of the informal economy on digital payments, and the implications of the effect for the adoption of CBDC, we undertake a preliminary analysis and estimated a multivariate cross-country regression analysis for a sample of 60 economies for the years 2013 and 2016 (the results are shown in Table 1). The negative relationship between the informal economy and digital payments indicates that countries with large informal sectors tend to have a small number of digital payment transactions6. In order to fight tax evasion, promote business transparency, and formalize the economy, several countries7 have employed specific tax measures to promote cashless transactions and banking channels (Awasthi & Engelschalk, 2018). Despite these efforts, digital payment adoption in developing economies is relatively low among businesses and households. Ligon et al. (2019) confirm that concerns about increased tax liabilities will hinder the adoption of digital payments by businesses and consumers.

| Variables | (1) 2013 | (2) 2016 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal economy | −2.128*** (−8.32) | −0.513* (−1.69) | −1.779*** (−9.21) | −0.219 (−0.93) |

| Control variables | ||||

| Financial depth | 31.614*** (3.95) | 19.811** (2.43) | ||

| Financial access | 6.734 (0.72) | 12.614 (1.21) | ||

| Log of GDP per capita | 11.879*** (3.13) | 13.468*** (3.72) | ||

| Trade openness | −0.005 (−0.29) | −0.006 (−0.24) | ||

| Inflation | 0.026 (0.08) | −0.382 (−1.47) | ||

| R2 | 0.525 | 0.805 | 0.494 | 0.775 |

| Observations | 60 | 58 | 60 | 57 |

- Note: This table reports cross-section estimation results for the years 2013 and 2016. The dependent variable is digital payments. Numbers in parenthesis are ordinary least squares standard errors.

- ***, **, and * represent 1%, 5%, and 10% significance.

- All variables are defined in Table 1 in Appendix A.

In accordance with this trend, there has been growing discussion among policy makers about the new payment technology—CBDC. Auer et al. (2020) analyze the economic and institutional drivers for CBDC issuance from the issuer's perspective (i.e., central banks).8 They find that an economy's digitization, innovation, informal economy, and financial development are positively related to a CBDC index that captures willingness to issue CBDC. Given the positive relationship between the informal economy and the CBDC index, it is likely that the authorities in a large informal economy, will have greater interest in a trail of transaction data, as well as a desire to reduce the use of cash. However, even if there were a fully functioning CBDC in operation, a monetary authority would prevent the government from completely phasing out cash as not everyone is willing or able to make digital payments. Vulnerable populations in many countries still live in digital poverty, and populations are aging. Millions of people in developing countries live in areas without broadband infrastructure and lack relevant digital skills. Vulnerable groups, which include retirees, people on a low-incomes, and those with certain health conditions, find it much easier to pay in cash than to use electronic payments, meaning access to cash is vital for these groups (Evans, 2020).

Authorities often fail to include end-user preferences, that is, the demand side of CBDC, in decision-making processes9. It is still unclear whether end users would prefer CBDC over other forms of payment, such as cash in an informal economy. CBDC is a new form of money that can be distinguished from cash and electronic money issued by commercial banks (Berentsen & Schar, 2018; Carstens, 2018). Physical cash is accessible to everyone on a peer-to-peer basis, offers full anonymity, and has no associated counterparty or cyber risk. However, it also has high transaction costs, does not offer interest, and has a fixed nominal value. The time costs of cash transactions include shoe leather costs—the distance between a customer and an ATM or bank branch—and cash withdrawal fees (Attanasio et al., 2002). Transaction costs also increase in places where individuals have limited access to formal financial services. CBDC could serve as a digital substitute for cash. It can have blend feature of cash and deposits (Agur et al., 2022). CBDC could be designed with no service or intermediary fees at the point of transaction and offer relatively cheap payment services. It can also provide high-speed electronic transaction services, since the payments are settled immediately at the point of transaction without going through the clearing process. An interest-bearing feature also offers a store of value as CBDC serves as a risk-free asset. Although an interest-bearing CBDC could lead to a risk of disintermediation as the users can switch their money (e.g., cash and deposits) into CBDC rapidly, such risk could be mitigated by complementary arrangements. For example, central banks can temporarily set a ceiling on the holdings of CBDC (Bindseil, 2020).

Taken together, the empirical findings and characteristics of CBDC imply that both the adoption and the effect of CBDC on the economy may differ depending on the size of the informal economy. The traceability of CBDC can benefit the government, which can efficiently trace tax evasion and other illegal activities and can help increase financial inclusion and the fluidity of the overall economy. However, consumers and businesses are unlikely to adopt a CBDC if it is less beneficial compared with cash payments. This argument provides motivation and guidance for our theoretical exploration.

3 THE MODEL

We extend some DSGE-based informal economy models such as Fernández and Meza (2015) and Orsi et al. (2014), to quantitatively study the relationship between CBDC and the informal economy. First, a money-in-utility (MIU) setup is used to capture liquidity services provided by multiple types of money (Uhlig & Xie, 2021). The MIU setup is also helpful in capturing several types of monetary friction, such as a “shopping time” friction in which real balances help to economize time spent on the purchase of consumption goods (Mehl et al., 2020; Niepelt, 2020). Moreover, we distinguish two types of money; namely cash and CBDC. Compared with cash, CBDC has negligible transaction costs but incurs government monitoring on household informal income. Hence, the use of CBDC creates a trade-off between cost efficiency and anonymity for households. Furthermore, we also consider the interest-bearing feature of CBDC, which could be remunerated similarly to bank deposits.

In theory, there are two possible designs for CBDC, including a cash-like and a deposit-like form. A purely cash-like CBDC could allow anonymous payments. However, many central banks are considering limiting the anonymity of CBDC since a fully anonymous CBDC design could allow for tax evasion, money laundering, illicit transactions, and financing terrorism (e.g., Bahamas Sand Dollar). Riksbank (2017) suggests that the Swedish CBDC, e-krona, will require registration and hence be traceable. ECB (2019) considers anonymity in small payment amounts only. Following the cases of traceable CBDC and the theoretical framework of Agur et al. (2022), CBDC in our framework has the mixed features of deposits and cash, along with a monitoring feature. Such a framework allows us to study the implications of the CBDC interest rate for the propagation of a set of conventional shocks, as well as a CBDC policy shock. We also consider the hybrid payment anonymity of CBDC in Section 3.1.2 as an extended analysis and robustness check.

3.1 Households

The representative household derives utility from consumption, money holding and leisure. Households supply formal and informal labor measured in hours, which is used for the production of formal and informal goods. Following Orsi et al. (2014), there is an informal labor-specific disutility which captures the lack of social protection in the informal sectors.

Equation (8) implies a negative relationship between CBDC money shares and the size of the informal economy given others remain constant. A sizable informal economy could prevent people from using CBDC as the detection cost is large.

3.1.1 With another digital payment

Given others remain constant, Equation (11) implies that the CBDC share would be smaller where a higher amount of digital payment is already in use in the economy. The presence of digital payment Dt reduces the convenience benefits of CBDC and dampens household's willingness to further replace cash with another form of digital payment (CBDC).

3.1.2 With tiering payment anonymity

In this subsection, we consider a scenario in which payment anonymity based on the CBDC has a hybrid structure, such as in the ECB (2019). An anonymous payment option is partially available (i.e., for small amounts), while identification is required for other payments (i.e., large or frequent payments).

3.2 Intermediate goods producers

3.3 Final goods producers

There is a continuum of monopolistic competitive final goods producers z, each of which is like a retailer, that buys intermediate goods and transfers them into differentiated final goods (Chang et al., 2019). The firms face nominal price adjustment costs following Rotemberg's approach , where Ωp measures the size of the adjustment cost, π is the steady-state inflation, and Yt is the aggregate output.

3.4 Equilibrium

which suggests a negative relationship between the detection rate and the incentive to engage in informal work.

4 CALIBRATION

Our calibration strategy is similar to that of Restrepo-Echavarria (2014). For parameters that are well-identified in the literature and typically less variant across countries, we give them fixed values. For other parameters which show significant cross-country differences or affect the CBDC informal-economy relationship, we consider a benchmark and some alternative values. In terms of the benchmark values, we mainly focus on Mexico, as it is considered as a representative emerging economy and has been extensively studied (see Aguiar and Gopinath (2007) among others).

Table 2 shows calibrated parameters. We set capital share α and capital depreciation rate δ as 0.35 and 0.05, respectively, in line with Fernández and Meza (2015). The discount factor β is calibrated as 0.99 to match the interest rate of 1.0145. The inverse labor elasticity is calibrated as 2, which is a standard value used in the literature. The money preference parameters ξ is calibrated as 0.02 based on money to output ratio (105%) for low- and middle-income countries. The ϕ is calibrated as 0.01 which implies that transaction costs account for 0.6% of output. This level is found in some Latin American countries such as Uruguay (Griffoli et al., 2018), European countries (Hasan et al., 2013) and Canada (Kosse et al., 2017). Following Restrepo-Echavarria (2014), we set the benchmark tax rate τ as 0.22. Given that the CBDC has not been issued, there is no target available to calibrate θ. We use a quadratic function to model the detection cost for households. A quadratic form is often used to model a cost function. This implies the elasticity of detection with respect to the CBDC share as unity. Our findings do not fundamentally change for alternative values of θ.11 Following Comin et al. (2014), the final goods mark-up parameter μ is calibrated as 1.1. The two adjustment cost parameters Ωp and Ωk are set to 22 and 4, respectively, which lie in the ranges considered in the literature (Chang et al., 2019; Christiano et al., 2005; Smets & Wouters, 2007).

| Parameters | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| α | Capital share | 0.35 |

| β | Discount factor | 0.992 |

| δ | Capital depreciation | 0.05 |

| η | Labor elasticity | 2 |

| ξ | Money preference | 0.02 |

| μ | Final goods mark-up | 1.1 |

| Ωp | Price adj. Cost parameter | 22 |

| Ωk | Capital adj. Cost parameter | 4 |

| ϕ | Transaction cost | 0.01 |

| τ | Tax rate | 0.22 |

| θ | Elasticity of detection rate | 1 |

| Steady state (ss) | ||

| 1+gy | ss per capita GDP growth | 1.006 |

| G/Y | ss exogenous demand share | 0.15 |

| H | ss labor hour | 0.33 |

| HI/H | ss informal labor share | 0.32 |

| Pr | No CBDC detection rate | 0.02 |

The lower part of Table 2 shows the calibrated values of the steady-state parameters. We set the quarterly output growth rate as 1.006, consistent with Fernández and Meza (2015). The exogenous demand share is calibrated as 0.15 to be consistent with data. We set ψ1 and ψ2 to match steady-state labor hour and informal labor share, respectively. The steady-state labor hour is calibrated as 0.33 as commonly used in the literature. In terms of informal labor share, we use 0.32 as in Fernández and Meza (2015) as the benchmark. This is a moderate level among others. For the detection rate Pr without CBDC, we choose 0.02 as the value based on Italy (Orsi et al., 2014) in the absence of other references. Finally, we defer the calibration of monetary policy parameters and shock processes to Section 6 as they do not affect the steady state.

5 STEADY-STATE ANALYSIS

As detailed in this section, we initially undertake a steady-state analysis by simulating the model to analyze the relationship between the informal economy and CBDC. Then in the following section, we further the analysis by considering the relationship within a business cycle framework using impulse response functions.

5.1 The effects of the informal economy on CBDC

Table 3 shows the model-predicted CBDC share based on the benchmark calibration and alternative informal economy shares as well. The experiment is done by changing the parameter ψ2 while the other parts of the model kept intact in order to capture the effect of the informal economy holding everything else constant. We do not claim that ψ2 is the only factor driving the informal economy. There are other factors which also affect informality, such as the tax rate and intensity of monitoring, which are captured by our model (see Equation (C8) in Appendix C). What matters for this experiment is not the reason for determining informality, but only that it is determined. We begin our analysis with a non-interest bearing CBDC for ease of comparison. Starting with a moderate informal economy share, such as the benchmark case (0.32), the CBDC share in money would be around 9%. This share indicates the economy has a low capacity to accommodate CBDC, and the likelihood of replacing a large amount of cash by CBDC would be low. As the informal economy share increases, such as the values for Brazil (0.43) and Thailand (0.55), the cost of holding CBDC (i.e., detection costs) would become higher relative to the benefits (i.e., efficiency and convenience gains), and hence would lead to even lower CBDC shares. On the contrary, with smaller informal economy shares, such as values for the US (0.1) and Spain (0.22), the detection costs relative to the benefits would be lower, and hence CBDC could be more acceptable in the economy. To summarize, Table 3 shows a negative relationship between the informal economy and the CBDC share, consistent with the theory proposed in Section 3.

| Informal share | US (0.1) | Spain (0.22) | Benchmark (Mexico, 0.32) | Brazil (0.43) | Thailand (0.55) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBDC share | 0.291 | 0.130 | 0.089 | 0.067 | 0.052 |

The relationship between the CBDC share and the original informal economy share

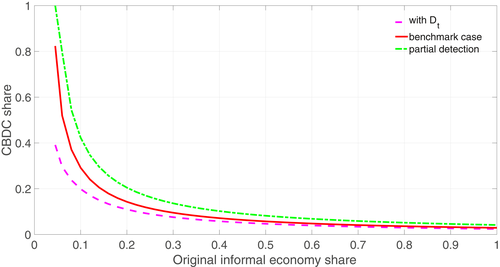

Figure 2 compares the benchmark CBDC informal-economy relationship with two alternative cases, including a case with another digital payment and the other one with a partial detection feature of CBDC. Not surprisingly, the presence of another form of digital money shifts the relationship downward. In the other case with a partial detection feature of CBDC, the relationship shifts upward, indicating that CBDC is more likely to be accepted given others remain constant. However, the negative and nonlinear relationship remains robust, especially when the original informal economy share becomes high.

Alternative CBDC-informality relationships

5.2 The implications of CBDC

Table 4 shows the impacts of CBDC on the economy. We focus on three key variables; namely detection probability, formal output share, and formalized output share. The formalized output is defined as the sum of formal output and detected informal output .

| Original informal share | 0.1 | 0.22 | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.55 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in detection prob (prt) | 4.250% | 0.840% | 0.400% | 0.220% | 0.140% |

| Increase in formal output share | 0.310% | 0.130% | 0.083% | 0.061% | 0.045% |

| Increase in formalized output share | 0.690% | 0.300% | 0.200% | 0.155% | 0.124% |

Similar to what is shown in Table 3, we consider five original informal economy shares. Table 4 shows negative relationships between original informal economy shares and their impacts on the three variables. With the original informal economy share increases, the increase in detection probability becomes smaller, thereby leading to less of an increase in formal and formalized outputs. As suggested by our previous analysis in Section 5.1, high original informal economy shares decrease household acceptance of CBDC, and through the spillover of CBDC on detection, the increases in formal and formalized outputs become smaller.

Among the five cases considered in Table 4, the most significant impacts from CBDC occur when the original informal economy share is 10%. In this case, the issuance of CBDC stimulates the detection rate from 2% to 6% and increases formal and formalized output shares by 0.3% and 0.7%, respectively. The increase in formalized output is larger than that of formal output because not only do some informal employees shift to formal production (increasing ) but also the detection of informal output becomes more effective (increasing ).

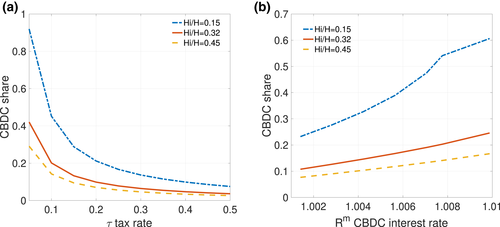

5.3 Roles of tax rates and CBDC interest rates

In this section, we consider alternative values of the tax rate τ and the CBDC interest rate Rm to study their implications and further understand the relationship between the informal economy and CBDC. As suggested by Equation (8), the tax rate and the CBDC interest rate are important determiners of the CBDC share.

Figure 3a suggests a negative relationship between the tax rate and the CBDC share. As the tax rate increases, incentives to engage in informal activities would be larger and the potential detection loss could be more significant. With such concerns, households would avoid detection due to the use of CBDC, which results in a lower CBDC share. This mechanism has important implications for the issuance of CBDC because a tax cut has the potential to encourage people to use CBDC. Compared to the benchmark result in Table 3 (8.9% of CBDC share), cutting the tax rate from 22% to 10% alongside CBDC issuance leads to a much larger CBDC share (20%). However, it should be noted that, on average, the tax rates in developing countries tend to be relatively low. Moreover, public debts in developing countries tend to be relatively high and tax is a key component of fiscal revenue. These facts imply limited policy space for tax reductions to promote the acceptance of CBDC. Given the aforementioned concerns, developing countries may consider limited usage of tax reductions when issuing CBDC.

The relationship between the CBDC share and the tax rate or the CBDC interest rate. (a) CBDC shares and tax rates. (b) CBDC shares and CBDC interest rates

Shifting our attention to the CBDC interest rate as an alternative policy tool, Figure 3b suggests a positive relationship between the CBDC interest rate and the CBDC share. A higher CBDC interest rate therefore adds one more benefit to hold CBDC in addition to the convenience gain, making CBDC more attractive to households. This mechanism implies that a positive CBDC interest rate enhances the acceptance of CBDC, which complements the effect of tax reduction. For instance, setting the CBDC interest rate as 70% of the deposit rate could double the CBDC share compared to the benchmark result.

Next, we investigate how the tax reduction and positive CBDC interest rate affect the role of CBDC in formalizing output. We consider three alternative tax rates in Table 5a, all of which are lower than the benchmark value (0.22). Unlike in Table 4 in which issuance of the CBDC only has minor impacts on formalized output share, Table 5a suggests more significant effects when the tax rate is lower. For example, when the tax rate is 10% and the original informal economy share is 32%, the issuance of CBDC could stimulate about 1% of formalized output share rather than 0.2% as in Table 4 (see the last entry in the fourth column of Table 4). If we further cut the tax rate to 5%, this effect can rise to 4.2%. A more formalized economy also provides a larger tax base, which partially offsets the fiscal burden which results from the tax reduction.

| Original informal share | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.45 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) With lower tax rates | |||

| τ = 0.05 | 8.45% | 4.19% | 2.85% |

| τ = 0.10 | 2.30% | 0.99% | 0.70% |

| τ = 0.15 | 0.97% | 0.44% | 0.31% |

| (b) With CBDC interest rates | |||

| rm = 0.3r | 1.29% | 0.55% | 0.38% |

| rm = 0.5r | 2.65% | 0.92% | 0.62% |

| rm = 0.7r | 4.19% | 1.53% | 0.98% |

- Note: τ is the tax rate. rm is the CBDC interest rate, shown as percentage of the conventional interest rate.

Turning to the CBDC interest rate, Table 5b suggests that a positive CBDC interest rate can also boost formalized output share. For instance, when the CBDC interest rate reaches 70% of the deposit rate and the original informal economy share is 32%, the issuance of CBDC could stimulate about 1.5% of formalized output share. This effect is much larger than the case of a zero CBDC rate (0.2%). The presence of a positive CBDC interest rate increases the CBDC share and strengthens its spillover effect on detection, which promotes both formal output and detected informal output.

6 IMPULSE RESPONSE ANALYSIS

In this section, we exploit the negative relationship between the informal economy and the CBDC share as established in Section 5 to investigate the implications of the relationship for business cycles.

We calibrate the Taylor parameters of conventional money policy ψr, ψy and ψπ as 0.8, 1.5, and 0.1, respectively, which are commonly used in the literature (e.g., Galí (2015)). These values are also used for counterpart parameters in the CBDC rate policy ρr, ρy and ρπ. In terms of shock processes, we estimate the persistence and volatility of TFP and government spending shocks using OLS based on the Mexican TFP and government spending data during the period 1990Q1–2018Q4. The estimated AR (1) parameters of the TFP shock (ρa) and that of the government spending shock (ρg) are 0.95 and 0.89 respectively. The shock volatility σa and σg are estimated as 0.91 and 1.02. The two monetary policy shock persistence parameters are set as 0.4 which is in line with the existing literature (e.g., Galí, 2015).

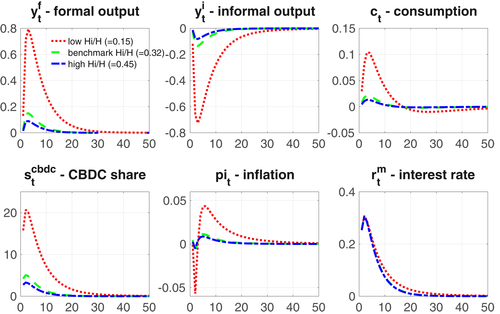

Figure 4 plots impulse responses of some key variables given a rise of 25 basis points of CBDC interest rate. An increase in the CBDC interest rate makes CBDC more attractive than cash, resulting in a higher CBDC share in the economy. Through the spillover effect on detection, the higher CBDC rate discourages tax evasion and triggers labor reallocation from the informal to the formal sector, thereby leading to an increase in formal output and a decrease in informal output. In addition to this reallocation effect, a higher CBDC shares reduce the transaction cost and hence stimulates consumption. Owing to both the reallocation and the cost-reduction effects, an increase in CBDC rate has an expansionary effect on the measured economy and is helpful to formalize the economy. Furthermore, we find that the effect of a CBDC policy shock can be stronger when the original informal economy share becomes smaller. In line with the steady-state analysis in Section 5, a small share of the informal economy results in more CBDC circulated in the economy, which makes the CBDC policy more powerful.

IRFs to the CBDC shock. We compare the cases with low (red lines), benchmark (green lines), and high (blue lines) informal economy shares

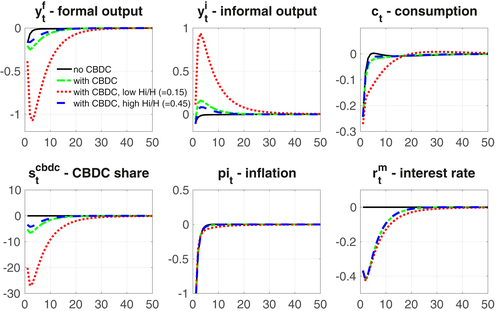

Figure 5 plots impulse responses to a tightened conventional monetary policy shock with an interest rate risen by 25 basis points. Consistent with findings in the literature, an increase in the conventional policy rate reduces output and curbs inflation. Responding to this, the central bank reduces the CBDC interest rate, leading to a decrease in CBDC share. Due to the spillover effect on detection, there would be a reallocation effect from formal to informal production. We can interpret the differences between the black line and the other lines in Figure 5 as additional effects of the monetary policy due to the CBDC rate adjustment. In this sense, the presence of CBDC can strengthen the effects of the conventional monetary policy on the formal output but dampen or even reverse the movement of informal output. Moreover, our results provide another angle (i.e., the informal economy) to address the coordination between CBDC and the conventional monetary policy (see Barrdear and Kumhof (2016); Brunnermeier and Niepelt (2019) among others). Furthermore, Figure 5 suggests that the additional effects provided by adjusting CBDC rates diminishes with the original informal economy share.

IRFs to the interest rate shock. We conduct two comparisons. The first one is comparing the cases with (green lines) and without CBDC (black lines); the second one is comparing the cases with low (red lines) and high (blue lines) informal economy shares

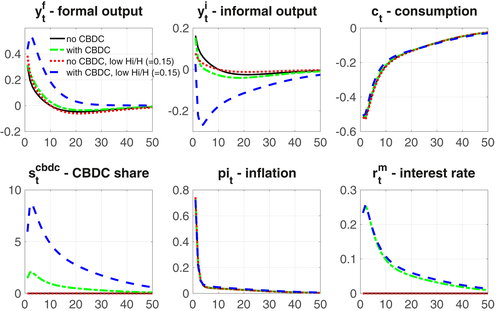

In terms of the government spending shock, Figure 6 shows that the presence of CBDC amplifies the response of formal output. Expansionary government spending heats the economy and results in increased CBDC interest rates. Consequently, there is an increase in CBDC shares which triggers a reallocation effect on labor toward the formal sector and thereby increase in formal output would be amplified. Comparing the difference between blue and red lines and that between green and black lines, we find that the amplification effect provided by adjusting CBDC rates diminishes with original informal economy shares. Such a finding is similar to that of conventional monetary policy shock. Furthermore, our results suggest that government spending is helpful to formalize an economy, which is consistent with existing literature (Mauricio, 2011; Restrepo-Echavarria, 2014)13. Unlike the literature in which government spending is linked to detection, we model a spillover effect of CBDC on detection and suggest coordination between monetary and fiscal policy in promoting formality.

IRFs to the government spending shock. We conduct two comparisons. The first one compares the cases with CBDC (green lines) and without CBDC (black lines); we also make a similar comparison (red lines vs. blue lines) when the informal economy share is low

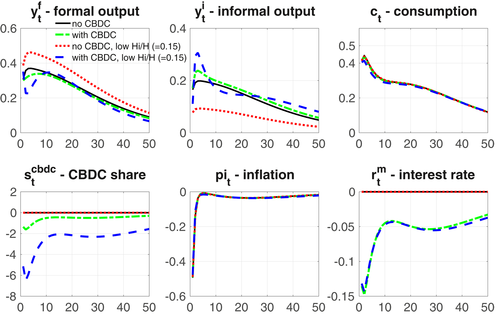

Contrary to the amplification effects from policy shocks, Figure 7 shows that the presence of CBDC dampens the response of formal output to a positive TFP shock. The positive TFP shock pushes down the price level, lowering inflation. The monetary authority decreases the CBDC policy rate, which leads to a decline in the CBDC share. This triggers a reallocation effect on labor toward the informal sector, which in turn leads to a decline in formal output.

IRFs to the TFP shock. The same as above

7 WELFARE ANALYSIS

This section examines the welfare implications of CBDC. We start by discussing alternative measures of welfare gains, followed by presentations and discussions of the results.

Table 6 reports the welfare gains of CBDC at different levels of informal economy shares. Overall, this table shows a positive welfare implication of CBDC conditional on both steady states and stochastic means. Focusing on the benchmark informal economy share (0.32), the issuance of CBDC would generate a consumption-equivalent welfare gain of 0.49% conditional on steady states and 0.53% conditional on stochastic means with TFP shock only. If we further account for interactions between CBDC and other shocks, the consumption-equivalent welfare gain would increase to 0.68%, indicating a larger welfare benefit from CBDC. Moreover, the welfare gain would decrease if the original informal economy share becomes high.

| Steady state | Stochastic mean | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| tfp shock only | All shocks | ||

| Hi/H = 0.15 | 1.3069% | 1.5527% | 2.5903% |

| Hi/H = 0.32 | 0.4908% | 0.5275% | 0.6782% |

| Hi/H = 0.45 | 0.3390% | 0.3610% | 0.4500% |

- Note: This table shows consumption-equivalent welfare gains of CBDC at different level of informal economy shares.

Next, we investigate how welfare gains interact with the relative productivity of the formal to the informal economy. By focusing on the stochastic means and the benchmark informal economy share, we compute welfare gains for different relative productivity (Af/Ai) which are summarized in Table 7.14 It shows that welfare gains from CBDC increase with higher levels of relative productivity. The increase in the productivity gap could raise the income gap between formal and informal sectors, leading to larger beneficial effects from formality on consumption and hence larger welfare-enhancing effects from CBDC.

| Relative productivity | Benchmark welfare measure | Preference on anonymous payment |

|---|---|---|

| Af/Ai = 1 | 0.6782% | 0.1414% |

| Af/Ai = 1.1 | 0.8049% | 0.1899% |

| Af/Ai = 1.2 | 1.2430% | 0.4699% |

- Note: This table shows consumption-equivalent welfare gains of CBDC conditional on stochastic means at different level of productivity gaps. The informal economy share is fixed at the benchmark case (0.32).

Welfare gains based on the alternative measure are reported in the last column of Table 7. There is an apparent decrease in the welfare gains compared to the benchmark analysis at each level of relative productivity. Taking 10% of the productivity gap as an example, the consumption-equivalent welfare gain of CBDC would be 0.19%, nearly a quarter of the benchmark result (0.8%). However, the relative rank of the welfare gain remains the same.

8 CONCLUSION

The ongoing development of CBDC spurs extensive discussions regarding the consequences of CBDC issuance. However, it remains questionable if CBDC would be accepted by end users. In this paper, we fill this gap by examining the relationship between the adoption of CBDC by end users and the informal economy, and further investigating the benefits of CBDC by exploiting cross-country differences in the informal economy. To this end, we develop a two-sector monetary model featuring three important elements of CBDC: cash-like convenience of use, deposit-like money, and a spillover effect on detection of the informal economy. These three factors formulate a trade-off between cost efficiency and anonymity for end users, and thus an endogenous relationship between CBDC and informal economic activities.

The theoretical result shows an L-shaped relationship between CBDC and the informal economy, suggesting that a sizable informal economy would decrease the adoption and usage of CBDC by end users. On the other hand, it confirms that the presence of CBDC is conducive to formalizing an economy by improving detection rates when households use CBDC services. Based on these relationships, we further investigate important economic implications of CBDC for business cycle stabilization. By adjusting the CBDC interest rate, the presence of CBDC can trigger a reallocation effect between the formal and informal sectors. Such an adjustment is helpful to stabilize measured output variation and enhance welfare. However, the welfare-enhancing effects become small if users strongly prefer payment anonymity.

Our results deliver a number of important policy implications. The presence of CBDC is helpful to formalize an economy. However, such benefits are not symmetric across countries. Developed countries with a lower share of the informal economy would find it easier to adopt CBDC; hence policymakers in such countries have greater flexibility to advance monetary and fiscal policies. On the contrary, developing countries which have high shares of the informal economy would find it harder to circulate CBDC and thus would only enjoy limited benefits. Our study also implies that tax reduction and a positive CBDC interest rate are useful tools to enhance the successful adoption of CBDC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the co-editor Steven Ongena and one anonymous referee whose suggestions greatly improved the paper. We also thank Lester C Hunt, Joe Cox, Stephen Millard, Peter Rosenkranz as well as conference and seminar participants at the Third CBDC Forum and the research seminar of the University of Portsmouth for helpful comments and suggestions. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. [Correction added on 2 July 2022, after first online publication: Peter Rosenkranz has been included in the Acknowledgments section in this version.]

ENDNOTES

- 1 By definition, CBDC is “an electronic form of central bank money that could be used by households and businesses to make payments and store value.” (Bank of England)

- 2 Bindseil (2020) suggests that CBDC could be helpful to overcome illicit payments and strengthen monetary policies.

- 3 There are many reasons why people value anonymity, which is unnecessary to be a monetary reasons, such as a desire for privacy (Low et al., 1994), or their own beliefs and morality (Goldberg & Lewis, 2000). In our framework, the preference for anonymity stems from informal incomes. We choose such a monetary reason due to modeling simplicity. Cash allows people to preserve their privacy. One may consider other forms of anonymity which could strengthen our argument.

- 4 Existing literature mainly focuses on transaction costs in cash management. In addition, the low transaction costs could be achieved by promoting financial inclusion since CBDC provides a gateway to access formal financial services (Griffoli et al., 2018).

- 5 Numerous countries have applied tax incentives to encourage the use electronic payments (Sung et al., 2017). For instance, Japan introduced the consumption tax reward point program for electronic payments in October 2019. In this system, cashless payment will receive certain percentage points (2% or 5%) or cash back.

- 6 The visual relationships between an informal economy and digital payments are shown in Appendix A.

- 7 For example, a 2% VAT refund is applied to any purchases made by credit card in Colombia, and some European countries, such as Greece, Hungary, and Italy, have introduced cash payment limits since 2012.

- 8 They develop a global CBDC project index capturing the central bank's progress toward CBDC. 0 indicates no announced project, 1 is in the case of public research studies, and 2 is an active or completed pilot.

- 9 Acknowledging the preferences of the end users is the key element for the high adoption rates of e-government services(Pleger et al., 2020).

- 10 CBDC could potentially promote financial access by providing an infrastructure on which financial services could be constructed.

- 11 For the reason of brevity, we do not include results based on alternative values of θ. They are available upon request.

- 12 In 2016, the US, Japan, and the United Kingdom show low levels of informal economic activities at 8%, 8.1% and 9.5% respectively. In contrast, Nigeria, Ukraine, and Sri Lanka show high level of informal economies at 53.4%, 43.9%, and 36.4% respectively.

- 13 In the literature, government spending could be in the form of purchasing formal goods and enhanced monitoring. They either provide direct support to the formal sector or discourage informal production, both of which contribute to a formalized economy.

- 14 Results based on non-stochastic steady states and stochastic means are qualitatively similar.